Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Uri Gal, Professor in Business Information Systems, University of Sydney

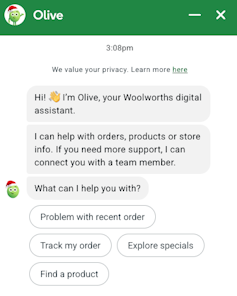

Woolworths has announced a partnership with Google to incorporate agentic artificial intelligence into its “Olive” chatbot, starting in Australia later this year.

Until now, Olive has largely answered questions, resolved problems and directed shoppers to information.

Soon, Olive will be able to do more: planning meals, interpreting handwritten recipes, applying loyalty discounts and placing suggested items directly into a customer’s online shopping basket.

Woolworths

Woolworths says Olive will not complete purchases automatically, and customers will still need to approve and pay for orders.

This distinction is important, but risks understating what’s actually changing. By the time a shopper reaches the checkout, many of the substantive decisions about what to buy may already have been shaped by the system.From helper to decision maker

The most significant change for shoppers is how decisions will be made during the shopping process – and who makes them.

Google describes its new system as a “proactive digital concierge” that understands customer intent, reasons through multi-step tasks, and executes actions.

Major United States retailers, including Walmart, Kroger and Lowe’s, are adopting the same technology. The move forms part of a broader strategy by Google to promote agent-based commerce across retail.

In practical terms, if Woolworths shoppers give their permission, the new Google Gemini version of Olive will increasingly assemble shopping baskets autonomously.

For example, a customer who uploads a photo of a handwritten recipe could receive a completed list of ingredients, reflecting product availability and discounts.

Alternatively, a customer who asks for a meal plan could receive a ready-made basket based on past preferences, current promotions and local stock levels.

This fundamentally changes the role of the shopper.

Instead of actively selecting products through browsing and comparison, shoppers will increasingly review and approve selections made for them. Decision-making shifts away from the individual towards the system.

This delegation may appear minor when considered in isolation. Over time, however, repeated delegation shapes habits, preferences and spending patterns. That is why this new change deserves careful scrutiny.

Nudging by design

Woolworths presents Olive’s expanded role as a practical convenience to save time and effort, while increasing personalisation. These claims are not incorrect, but they obscure an important point.

Agent-based shopping systems are designed to nudge behaviour in ways that differ markedly from traditional advertising.

When Olive highlights discounted products or promotional offers for a shopper, it doesn’t rely on neutral criteria. Instead, its priorities reflect pricing strategies, promotional priorities and commercial relationships – not an objective assessment of the consumer’s interests.

Once such judgements are embedded within an AI system that guides shopping decisions, nudging becomes part of the structure of choice, rather than a visible layer placed on top of it.

Read more:

Nudge theory: what 15 years of research tells us about its promises and politics

This is a particularly powerful form of influence. Traditional advertising is recognisable. Shoppers know when they are being persuaded and can discount or ignore it.

Algorithmic nudging, by contrast, operates upstream. It shapes which options are surfaced, combined, or omitted before the shopper encounters them. Over time, this influence becomes routine and difficult to detect.

Agent-based shopping also means AI does the browsing, comparing prices and weighing alternatives for us. Shoppers are increasingly presented with curated outcomes that invite acceptance, rather than deliberation.

As fewer options are made visible and fewer trade-offs are explicitly presented, convenience begins to replace informed choice.

For these reasons, it would be wrong to treat agent-led shopping as value neutral. Systems designed to increase loyalty and revenue should not automatically be assumed to act in the best interests of consumers, even when they deliver genuine convenience.

Unresolved data privacy questions

Data privacy is an even greater concern.

Grocery shopping reveals far more than brand preference. Meal planning can disclose health conditions, dietary restrictions, cultural practices, religious observance, family composition and financial pressures. When an AI system manages these tasks, domestic life becomes legible to the platform that supports it.

Google has stated customer data used in its system is not used to train models and that strict safety standards apply.

These assurances are important, but they do not resolve all concerns. It’s not yet clear how long household data is retained, how it’s aggregated, or how insights from such data are used elsewhere.

Consent offers limited protection in this context. It is typically granted once, while profiling and optimisation continue over time. Even without direct data sharing, inferences drawn from household behaviour can shape system performance and design.

These privacy risks do not depend on misuse or data breaches. They arise from the growing intimacy of data used to shape behaviour, rather than merely record it.

Convenience shouldn’t end the conversation

For many households, Olive’s expanded capabilities will save time, reduce friction and improve the shopping experience.

But when AI moves from assistance to action, it reshapes how choices are made and how much agency people give up.

This shift should prompt a broader discussion about where convenience ends and consumer autonomy begins. When AI systems start making everyday decisions, we must ask whether consumers retain meaningful control over their choices.

Transparency about how recommendations are generated, limits on commercial incentives shaping agent behaviour, and boundaries on household data use should be treated as baseline expectations, not optional safeguards.

Without such scrutiny, agent-led shopping risks quietly reconfiguring consumer behaviour in ways that are difficult to detect – and even harder to reverse.

![]()

Uri Gal does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Do Woolworths shoppers want Google AI adding items to buy? We’ll soon find out – https://theconversation.com/do-woolworths-shoppers-want-google-ai-adding-items-to-buy-well-soon-find-out-273342