Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Nathan Kilah, Senior Lecturer in Chemistry, University of Tasmania

Christmas means different things to different people. For me, it’s an opportunity to eat celebratory foods that aren’t available all year round.

The top of my list is glazed ham, but a very close second is a well matured Christmas pudding with different dairy-rich trimmings.

But what chemical transformations are involved in making a Christmas pud? Here’s the science.

Complex flavour profiles

A Christmas pudding is a steamed dessert consisting of dried fruits, sugar, flour, fats, spices, eggs and alcohol. It is often cooked well in advanced and left to mature, then steamed or reheated before serving.

Modern puddings tend to use dried grapes (raisins, currants and sultanas) and candied fruits such as cherries and citrus peel.Dried fruits have different flavour profiles compared with fresh fruits. Many of the volatile flavour compounds are lost but new flavours develop. These can be formed by enzymatic browning (like when cut fruit turns brown), reactions with light, and transformations of fatty acids and even natural colours into flavour compounds.

Candied or glacé fruits such as cherries and citrus peel are made by heating the fruit in a sugar syrup. The water content of the fruit is replaced by sugar, leaving a chewy, sweet, but less colourful product.

This sugary environment is inhospitable to microbes. The water from bacteria and fungi is removed on contact with the sugary surface due to a process known as osmosis.

Dried fruits for a Christmas pudding are typically soaked in alcohol for hours, days or weeks, depending on the recipe. This ensures the fruits are moist in the final pudding, while also adding flavour.

Soaking rehydrates the fruits, ensuring they do not draw moisture from the pudding mixture. The presence of ethanol (from brandy, rum or cognac) also inhibits the growth of microbes.

Suet and spice and all things nice

The most common spices in pudding are cinnamon, nutmeg, allspice, mace and cloves. Each spice brings a unique chemical signature to the dish.

Some notable chemicals are cinnamaldehyde from cinnamon, eugenol from cloves and allspice, and sabinene from nutmeg.

A pudding is not a cake but it contains many of the typical cake ingredients: flour, baking powder, eggs and fat. The flour helps to absorb moisture and gives texture (the “crumb”), while the baking powder acts as a raising agent. The lecithin from the egg yolks acts as an emulsifier, helping keep the mixture together.

Suet (which comes from the fat around the loins and kidneys of beef cattle) is the traditional fat used in Christmas puddings. The fat adds richness and can keep the crumb moist by binding to starch from the flour. Many modern commercial puddings replace suet with vegetable oils.

Once mixed, the pudding mixture is placed into a pudding basin, sealed or wrapped, then steamed.

Scientifically, steaming has advantages over other cooking methods for transforming the batter into a set pudding. The temperature of boiling water and the steam it produces is a consistent 100°C, so there’s no danger of burning the sugar-rich mixture and fruits or drying it out.

At this temperature, the starches in the flour are gelatinised, egg proteins unravel (known as denaturing), and the baking powder is activated. This makes the pudding rise and set.

Once cooked, the pudding can be stored for weeks or even longer. Cooks will often “feed” their pudding weekly with additional alcohol, bolstering the flavour and keeping microbes from spoiling the pudding.

A dramatic (and generally unnecessary) addition to the Christmas pudding tradition is to pour over a warmed, high-percentage alcohol and light it on fire. The flame of burning ethanol is generally blue.

The blue colour indicates a complete combustion, where all the ethanol is consumed. The orange flame we usually associate with fire is due to incomplete combustion, where carbon soot formed in the flame emits light due to being heated (this process is known as incandescence).

Photo by You Le on Unsplash

Liquid fuel fires, particularly those with near-invisible flames, can be very dangerous, so plan ahead if you want to set your pudding on fire. Never move around a flaming dessert and remember: more fuel isn’t always better.

Coins and plum puddings

Another Christmas tradition was to include good luck tokens and trinkets (including a chicken wishbone!).

A common inclusion was threepence and sixpence coins, which in Australia were made from alloys of silver and copper. The conversion to decimal currency in the 1960s, and the “debasement” from silver coins, prompted a study on the effects of puddings on coins.

It turned out the new copper-nickel alloy made the surrounding pudding green and imparted an unpleasant flavour. The five and ten cent coins were considered suitable for inserting after cooking but just before eating, but could present a choking hazard.

Silver pudding coins are sold for those keen to carry on the tradition. Just make sure your guests are informed, for the sake of both their teeth and digestive tract.

Wikimedia/Kurzon, CC BY

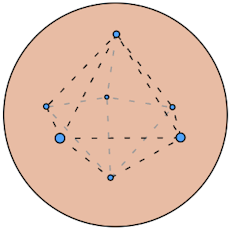

As a young chemistry student, I remember learning about the “plum pudding” model of the atom – a now-defunct idea floated in the early 1900s by British physicist J.J. Thomson. He envisioned the atom as a sphere with electrons lodged in it like plums in a pudding.

Modern chemistry has moved on from this model – but I have not moved on from puddings. I still love them.

Whether you opt for a pudding or a modern pavlova, be sure to embrace the chemistry that makes your Christmas deliciously jolly.

![]()

Nathan Kilah does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. ‘Never move around a flaming dessert’: a scientist explains the chemistry of a Christmas pudding – https://theconversation.com/never-move-around-a-flaming-dessert-a-scientist-explains-the-chemistry-of-a-christmas-pudding-268392