Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Samuel Cornell, PhD Candidate in Public Health & Community Medicine, School of Population Health, UNSW Sydney

If you’ve spent even a little time on social media in recent years, you’ve no doubt come across a swathe of “wellness” content.

From kilometre-long lines of runners strutting the Bondi promenade at 6am, to a surge in sauna and ice bath studios, to bizarre routines such as mouth taping, longevity diets and facial ice rollers – looking well is so hot right now. And being seen to be well has become the social currency of our times.

But perhaps there are also other forces at play here, as wellness culture seems to tap into age-old human preferences for vitality, fertility and social status.

Read more:

Why do smart people get hooked on wellness trends? Personality traits may play a role

Is 50 the new 20?

Humans evolved to notice and prefer visible signs of health. Outward signs of potentially contagious disease tend to evoke disgust reactions in us. This is part of the “behavioural immune system” – a series of preferences we evolved to avoid infection over thousands of generations when contagious diseases were both more common and less well understood than they are today.

But there’s more to it than just avoiding people who might be infectious.

Research suggests we are often drawn to people who have glowing skin, symmetrical faces, healthy body composition, and who move elegantly .

These might historically have been cues of health, and perhaps of good genes for staying healthy.

Modern technologies make it possible to fake these cues. That may be part of the secret of wellness culture’s success: it hijacks and exaggerates ancient cues of health.

Skin-focussed wellness routines, such as taking collagen powders, or bathing in LED light, are appealing because they seek to amplify perceived youthfulness. Cues of youthful nubility are associated with fertility and with the chances of a successful first pregnancy.

This is important because throughout most of human history, our ancestors were typically those women who safely bore children.

Ancient signals, modern wellness

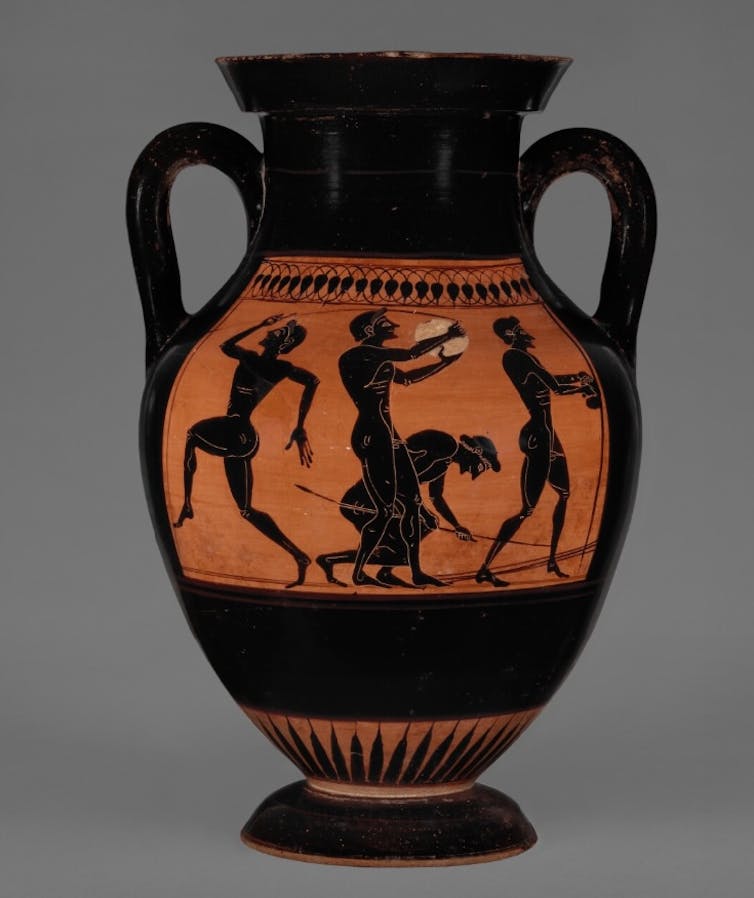

Our social preferences at least partly evoke the biological realities of the ancient past where they evolved. Today, people have access to tools such as makeup, cosmetic surgery and wellness culture, that let them hijack these preferences. Once you get used to this idea, you start to see it everywhere.

Running clubs are an arena for youthful people, and those clinging to youth, to display their social energy and endurance. It’s easy to imagine how these traits can be inferred as signs of health, sociability and cooperation. No wonder many of these clubs are becoming dating scenes.

The J. Paul Getty Museum

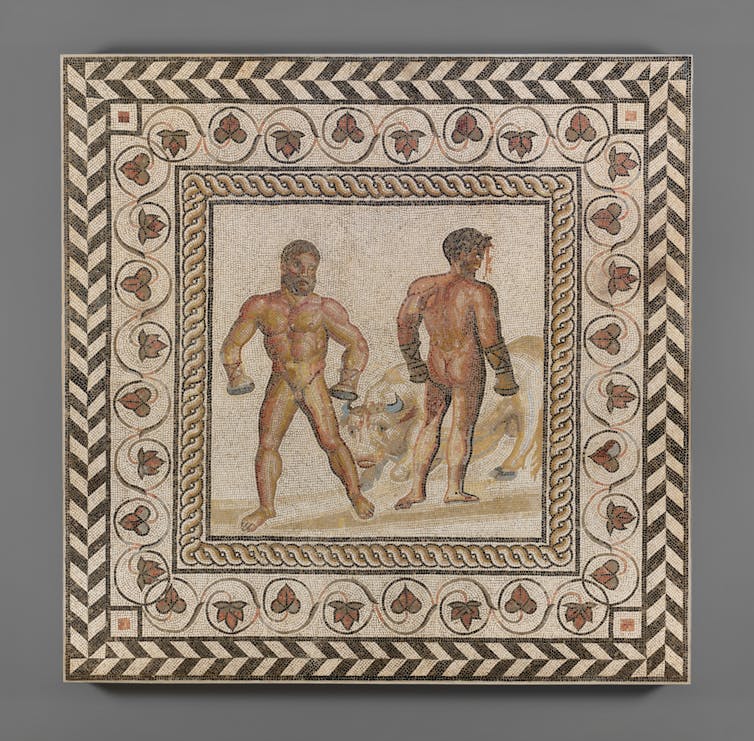

Even cold plunges into ice baths provide not-so-subtle signals of toughness, resilience, pain tolerance and willingness to take physical risks – traits which may be valued by a potential mate.

However, when it comes to evolutionary science, it is often bad form to make up credible stories for how each trait came to be as it is, and to stop there. Scientific theories have to be tested carefully against evidence, not the “pub test”. That presents a challenge.

Why wellness spreads quickly

There may be another evolutionary explanation that fills out the picture, and complements the approach of looking at one wellness trend after another, and trying to work out what they might signal.

The evolved capacity for playing “status games”, as author Will Storr puts it, is already well established.

Yoga retreats and supplement stacks don’t come cheap. Ice baths aren’t particularly comfortable. Ultramarathons always hurt.

At the same time, these activities signal a person has the interlinked luxuries of leisure time and wealth, as well as personal qualities such as discipline, perseverance and commitment.

The J. Paul Getty Museum

Spend a little time on Strava, the social media platform where endurance athletes post their activities, and you can see status games being played in real-time.

People are avid copiers of status signals and this is especially true in teens and young adults. Moreover, social media algorithms learn to amplify signals of prestige, emotional content, and content that appears to speak to an in-group, to maximise engagement.

And what is a run club, or a gym culture, or a diet fad, if not an in-group?

All is not necessarily well with wellness

Photos of beautiful poreless skin, sculpted bodies and picture perfect sunrise runs are supernormal stimuli – exaggerated versions of normal cues that cause a strong reaction, and often attraction, both online and in “real life”.

But all the downsides of social media signalling still apply, even when the topic is ostensibly about health.

Ice baths can result in cold shock or hypothermia, overtraining causes injuries, and much of the advice and recommendations from wellness influencers are not just nonsense – they can be actively harmful.

What people are imitating status rather than health, the evolutionary picture becomes even clearer: humans have long copied the behaviours of high-status individuals. Doing so improved survival and reproductive opportunities, and built the norms of our institutions.

But this eagerness to copy can misfire. Copying the practices of high-status individuals — whether they are extreme diets or punishing training schedules — can come with a great cost, especially when the signals are exaggerated for online display.

Wellness culture doesn’t just reflect evolved preferences for health and status; it can exploit and distort them. Beware the urge to signal wellness, as it could be leading you astray.

![]()

Samuel Cornell receives funding from an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.

Rob Brooks receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

– ref. Ice baths and marathons: our modern obsession with ‘wellness’ is driven by ancient instincts – https://theconversation.com/ice-baths-and-marathons-our-modern-obsession-with-wellness-is-driven-by-ancient-instincts-270172