Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Ailie Gallant, Associate Professor, ARC Centre of Excellence for Weather of the 21st Century, Monash University

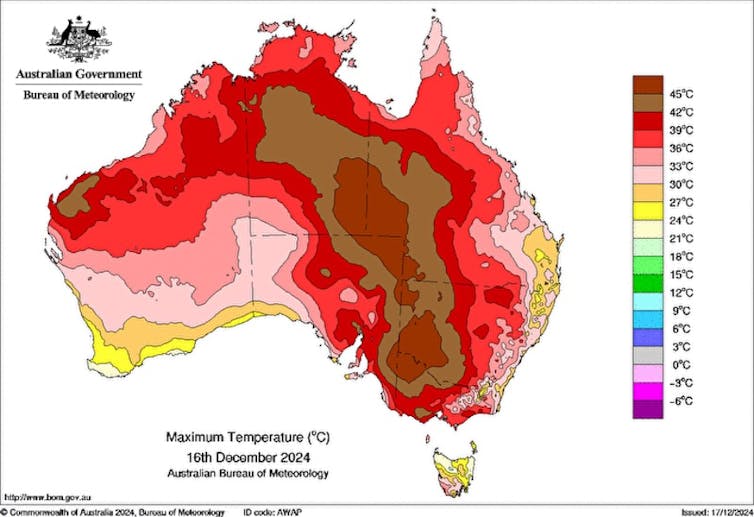

As a dome of heat developed over north and central Australia last weekend, parts of the country braced themselves for their first taste of summer temperatures well in excess of 40°C. Some areas expected their hottest temperatures since the Black Summer of 2019–20.

The southeast was on high alert, with searing heat and gusty winds expected, bringing the threat of extreme fire conditions through South Australia and Victoria on Monday and into New South Wales on Tuesday. The north and central parts of Australia were expected to swelter through the week.

But as the furnace drew closer, many people who kept a watchful eye on the forecast would have noticed something. In some parts of the country, the forecast bounced around in the lead up to the event.

For example, in the week leading up to the day of extreme heat on Monday, the forecast for Melbourne flip-flopped between approximately 35°C and 42°C, settling on 41°C for a couple of days before the event.

So what was it going to be? Just a very warm, but manageable day? Or the kind of highly unusual heat not experienced for several years?

Weather forecasting is a science, not an art

Predicting anything about the future, with accuracy, is hard.

Think about a forecast for your day tomorrow. You might predict that you will get up, eat breakfast, get the kids ready, go to work, finish a report, have a meeting, do some Christmas shopping, pick up the kids, and cook dinner.

But reality might differ from what you predicted. Your meeting might run late, causing you to skip the shopping, for example.

Forecasting your day a week ahead of time is even harder, because there are more things that will change because of decisions you make in the next couple of days (like whether or not you’ll have a spare hour to get that Christmas shopping done on the weekend).

Weather forecasts work the same way. For an accurate forecast, we need to know (as best we can) what is happening in the atmosphere right now, based on millions of observations taken around the world. We then use computer models that take the state of the weather now and use physical equations to project that state forward in time, which gives us a weather forecast.

Like our personal plans for this time next week, weather forecasts 7–10 days ahead provide only a rough guide of what to expect. Small, seemingly insignificant errors in atmospheric measurements grow over time, leading to big changes in the forecast, known as the “butterfly effect”.

The further ahead we predict, the more these errors accumulate.

To counter this, forecasters run models multiple times based on slightly different versions of the current atmosphere. This creates an ensemble of forecasts showing a range of possible outcomes. The more these forecasts agree, the more certain we are about the upcoming weather.

Prediction ping-pong

So why do weather forecasts change? It happens because of the range of possible outcomes – our ensemble of forecasts – just described. And sometimes, little changes in the forecast can make a big difference to the outcome.

Let’s take the example of the extreme heat in Melbourne on Monday. The precise forecast of the maximum temperature depended on two main factors: the timing of the cold front and cloud cover.

A cold front was expected to come through and end the high temperatures, but when? If it crossed in the afternoon, temperatures might peak in the mid to high 30s, but if it didn’t arrive until the evening the mercury might hit the low 40s.

Additionally, more cloud cover would lower the temperature, and less cloud cover would increase it.

Bureau of Meteorology, CC BY

As it turns out, the official Bureau of Meteorology maximum temperature forecast was for 41°C across the broader Melbourne metro area. And while Geelong and the western suburbs hit at or very near that mark, the city and eastern suburbs remained below 40°C (just), hitting 39.4°C at the city’s Olympic Park station near 6pm.

But several stations in east and southeast Melbourne barely cracked 37–38°C. The culprit in this case was cloud cover, which persisted over the city centre and the east, but largely cleared to the city’s west.

Should we trust weather forecasts?

Weather forecasting is not always perfect, but it is useful and forecasts are trustworthy.

Take this heat event: forecasts first showed that Monday would be extremely hot up to ten days prior and were showing the possibility of a 40°C day for Melbourne up to seven days ahead.

Twenty years ago, being able to forecast this week’s event with this kind of precision would have been unthinkable. Forecasts for seven days ahead are now as accurate as three day forecasts were 40 years ago – a remarkable scientific achievement.

In the lead up to Christmas, forecasts are showing the potential for more hot weather for the southeast towards Boxing Day, with some models predicting Melbourne could once again reach into the 40s.

Small, almost imperceptible imperfections may change this forecast as we get closer to Boxing Day. No matter what your favourite weather app is predicting, rest assured, your local weather forecaster is analysing all possibilities and providing you with the best forecast available.

![]()

Ailie Gallant receives funding from the Australian Research Council and the Australian Government Department of Climate Change, Energy, Water and the Environment.

Michael Barnes receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

– ref. Australia’s latest brush with extreme heat shows just how good weather forecasting really is – https://theconversation.com/australias-latest-brush-with-extreme-heat-shows-just-how-good-weather-forecasting-really-is-246127