Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Thami Croeser, Research Officer, Centre for Urban Research, RMIT University

Imagine you’re a fairywren living in a patch of scrub behind a schoolyard in the suburbs. It’s been pretty nice so far, but a recent increase in neighbourhood cats and the council’s insect control tactics mean it’s time to look for somewhere safer to live.

There’s a problem, though. You’re a small, bright blue bird that tends to make short flights from shrub to shrub, staying safe in the foliage. Beyond your little patch of habitat, there don’t seem to be any places you can easily access. On one side are wide-open sportsfields; on the other, a busy six-lane road. Where do you go?

It’s a bad situation for a fairywren, and for many other native species in cities. In ecology, we call this habitat fragmentation.

The map of suitable habitat for city-dwelling wildlife often looks like a scattering of islands in an inhospitable sea of other land uses. These species face threats or barriers such as roads, buildings, fences and feral predators. This poses several issues, such as barring access to feeding areas, increasing competition for nesting spaces within habitat patches and even reducing gene flow by making it hard to find mates.

Our newly published research shows how native species in our cities can benefit if we focus on creating strategically located green spaces to connect isolated patches of habitat.

MomentsForZen/Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND

Why we should care for urban species

Despite the myriad challenges facing plants, animals and insects in urban areas, cities are important places to take care of our native species. Urban areas still offer valuable nesting and feeding resources, especially for tree-dwelling mammals, canopy-feeding birds and water-adapted species.

In addition to their value for conservation, urban habitats are precious spaces for people to encounter nature in the places we live and work. Urban nature has been shown to be important in balancing out the stresses of city life, particularly in disadvantaged communities. It’s also good for our physical health and social connectedness – it even improves cognitive development in children.

Unsurprisingly, studies have shown people want more nature in their cities.

But actively supporting native species hasn’t generally been the norm in many cities. The practice of planning and design to deliberately bring nature back into urban areas is still developing. Our open-access research paper in Landscape and Urban Planning offers insights into how we can tackle one aspect of the problem: habitat fragmentation.

What did the study look at?

We examined how greening projects could best connect up habitat for New Holland honeyeaters (Phylidonyris novaehollandiae), blue-banded bees (Amegilla spp) and mole crickets (Gryllotalpa spp) in Melbourne, Victoria. These are all species that occur locally but experience some degree of habitat fragmentation.

We have a lot of greening to do for climate adaptation and to create open space for new residents in our growing cities. What if we could also do this greening in a way that boosts habitat for non-human residents too?

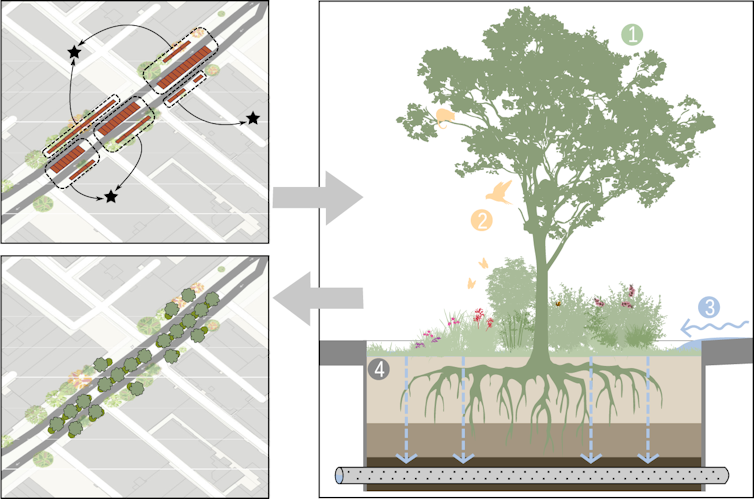

We compared a scenario where a large number of small green spaces (formerly parking spaces) were created mainly for climate adaptation purposes, to a pair of scenarios where a smaller number of green spaces were created exclusively in areas that had been identified as key links between habitat fragments.

T. Croeser et al 2024, CC BY

What were the findings?

In total, the benefit of each space in the targeted scenario was more than double that of the scenario where we placed green spaces for climate adaptation purposes, even with the same design of individual green spaces.

Here’s an image of the kind of green spaces we modelled in this study.

T. Croeser et al 2022, CC BY

We found significant benefits for two of our three species when green spaces were located in a way that specifically targeted habitat connections.

Blue-banded bees and mole crickets did especially well. It is trickier for these small creatures to navigate the space between habitat patches. When these small green spaces provided “stepping stones” between bigger patches, they greatly increased the area of habitat a bee or cricket could reach.

AjayTvm/Shutterstock

Donald Hobern/Flickr, CC BY

Linking up habitats when we create new green spaces is one way to give native species a chance in our cities. It also gives us (and our kids) a better chance of having everyday nature experiences.

Of course, adding this “ecosystem connectivity” lens to our green space planning isn’t a biodiversity panacea. We’ll still need to deliver a lot of new greenery.

And we’ll have to design it carefully to support native animals while also providing cooling, reduced flood risk and recreational spaces. We also need to make sure we’re picking the right species to model our maps on, and then design our spaces for.

Still, if we get this right, that fairywren might just one day have small, green “stepping stones” to find their way around the city to a happy new home.

![]()

Thami Croeser receives funding from the Ian Potter Foundation.

Holly Kirk receives funding from the Australian Research Council and the Ian Potter Foundation.

– ref. Stepping stones for wildlife: how linking up isolated habitats can help nature thrive in our cities – https://theconversation.com/stepping-stones-for-wildlife-how-linking-up-isolated-habitats-can-help-nature-thrive-in-our-cities-234923