Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Thao Phan, Research Fellow, Emerging Technologies Research Lab, Monash University

The chief executive of drone delivery company Wing says 2024 is “the year of drone delivery”. The company first went public in 2014 as a Google “moonshot” project and now operates in several cities in Australia, the United States and Finland, with plans to expand further.

Wing promises fast, cheap delivery of food and groceries at the touch of a button, with critics voicing concerns about personal intrusions such as noise and privacy. But what are the real challenges of having delivery drones in your neighbourhood?

To find out, I’ve been spending time in Australia’s “drone zones”, interviewing residents and local business operators in trial suburbs across Canberra and Logan in Queensland. It turns out noise and privacy aren’t their main problems.

Instead, people talked about larger, infrastructural issues – bad traffic, poor public transport, and other failures of urban planning – and how drone delivery is being proposed as a band-aid solution.

How does Wing work?

For customers, Wing works much like UberEats or Menulog: people place orders and pay via an app. On offer are lightweight, mundane items from various suppliers, such as takeaway coffees, sushi rolls and small supermarket goods.

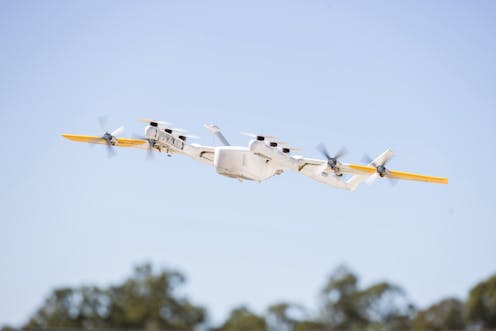

What’s different is the delivery. A small autonomous drone with its own sensors and navigation system brings the package by air.

Wing

In community trials, delivery times have been incredibly fast. The average time is ten minutes, with the fastest-ever delivery – from order placement to arrival at the doorstep – taking 2 minutes and 47 seconds.

Wing conducted its first trials in the rural town of Royalla near the border of New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory. Australia has been a test bed for its systems ever since.

In my research on drone delivery in Australia, I’ve been spending time in Canberra and Logan, observing the trials and interviewing locals about what life with drone delivery is actually like.

There were differing views on issues like noise and privacy. For instance, some people weren’t bothered by noise while others likened it to a “jumbo whipper snipper”. But of bigger concern was what Wing signalled for the future of urban planning and the viability of small business.

Sustainability that relies on cars and traffic

One of Wing’s strongest pitches to government and residents alike has been that its battery-powered drones offer a zero-emission, fast, sustainable solution to “last mile” delivery. In effect, Wing promises to take cars off the road by adding drones to the sky. However, its current business model relies on traffic congestion and poor urban planning.

The areas Wing has targeted have major infrastructural issues. While Wing may offer a quick fix for these problems in the short term, in the long term the company’s success relies on roads staying congested and neighbourhoods being unwalkable. This is a major red flag for these communities who would rather see a better transport system on the ground than more drone traffic in the sky.

From Wing’s perspective, according to a spokesperson:

Wing provides a useful service for people who live in areas that experience heavy traffic congestion […] We think drones are a better vehicle match for moving a small package when other efficient means aren’t available.

In my interviews with residents in Browns Plains (in Logan, south of Brisbane) and Gungahlin (in Canberra), our conversations would quickly turn from drones to poor public transport and roads:

Honestly, it’s terrible. We have buses that take an hour just to get to Woodridge. It’s literally a 13-minute drive down the road and it takes ages to get there. The traffic is always crap.

Parking was also a major complaint in these areas:

The planning of Gungahlin, it’s like things have just been added on. The huge growth in a lot of high-density buildings has made a huge difference to parking and things when people want to go shopping […] there’s not enough parking.

Abandoning small business in favour of big partnerships

In 2019, when Wing first landed in the city of Logan in Queensland, it partnered exclusively with local businesses. In theory, Wing would help these businesses reach new customers and “take [them] to new heights”.

This strategy was incredibly successful. Local hardware stores, coffee shops and grocery stores provided stock for Wing’s warehouses. In 2021, Wing declared Logan “the drone delivery capital of the world”.

But in 2022 Wing began to pivot to a model that was easier to scale up. Instead of stocking and supplying its own warehouses, or managing its own delivery app, Wing struck deals with big retail players including Coles and DoorDash.

Both customers and local businesses feel left in the lurch. As one resident told me:

The reason we started to go on there was, well, you can still support local. Get it delivered pretty cheap, and [there’s a] convenience factor. And then when they’ve taken everything off, like Boost [Juice] is probably the only one really that I use on there now, and that’s through DoorDash, not even through them direct.

Another business owner said he felt “ditched”:

They put an end date to it and said “We’re redoing the way we’re doing business.” […] They decided to cut their costs even though they’re owned by Google, they got a lot of money. They’re going to use the rooftop space from the big shopping centres and launch the drones from there and use the stock from Coles or whoever they were dealing with at the time.

Wing’s large partnerships also make it harder for small businesses to compete. A local neighbourhood shop cannot meet the expectation of ten-minute delivery, and delivery platform commissions of up to 15–20% will also cut into their margins.

A Wing spokesperson told The Conversation the company is offering delivery services to more small businesses than in the past, adding “68% of restaurants and merchants on the [Wing] marketplace are independent small businesses that aren’t affiliated with a national chain or brand”.

Long-term impacts

The picture emerging from my interviews shows drone delivery started out as a nice enough novelty, but potential long-term impacts on the liveability of neighbourhoods are becoming clear.

Wing’s innovations are not only technical – things like autonomous drones, physical infrastructure, and traffic management systems – but also social and regulatory. The partnerships with major retailers and property developers are no less significant, and the company is also involved in the development of new regulations and safety standards for drones. As a subsidiary of the multitrillion-dollar US tech conglomerate Alphabet (the parent company of Google), Wing has significant resources to throw at making sure its business succeeds.

Wing has said Australia represents the future for drone delivery. By listening to the stories of people who are already living with drone delivery, we can learn more about their risks and unexpected impacts.

Are delivery drones operating in your neighbourhood? Our team is collecting photos, videos and stories about what it’s like to live with drone delivery. Please make a contribution and help us understand what our future could be like.

![]()

Thao Phan is employed in the ARC Centre of Excellence on Automated Decision-Making & Society (ADM+S). Her research is funded by the ADM+S, the UKRI Bridging Responsible AI Divides Programme, and the Monash-Warwick Alliance Fund.

– ref. Is drone delivery a modern miracle or a band-aid fix for poor urban planning? I went to Australia’s ‘drone zones’ to find out – https://theconversation.com/is-drone-delivery-a-modern-miracle-or-a-band-aid-fix-for-poor-urban-planning-i-went-to-australias-drone-zones-to-find-out-232977