Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Will Visconti, Teaching staff, Art History, University of Sydney

Alphonse Mucha’s body of work is full of contradictions.

He is most often identified with late 19th-century Paris, but was in fact Moravian (Czech). His vision for the purpose of art was for the betterment of humanity and creation of utopia, but his most famous artworks are advertisements. His style typifies Art Nouveau, a movement at its peak between the 1890s and 1910s, but his career spanned several decades from the late 1800s until his death in 1939.

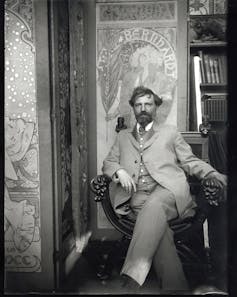

Born in 1860 in what is now the Czech Republic, Mucha trained in Paris. He worked as an illustrator in Paris and Prague, and exhibited work in the Paris Salon before rising to fame with his poster works and branching out into other media. After several visits to the United States, he returned to his homeland in 1910 and remained there until his death in 1939.

A new exhibition of his work at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, the largest of its kind seen in Australia with over 200 pieces on display, shows the full breadth of Mucha’s work and his commitment to the transformative power of art across media.

Art and ideals

The twin concerns of Mucha’s art are beauty and identity, specifically, national identity.

This may provide the biggest surprise to viewers who recognise his work, showing the extent of his productivity over so many decades and multiple media. Not only did Mucha compose his iconic posters and design jewellery, but he created murals for Czech municipal buildings and a portfolio of designs for interiors.

Significantly, he also designed postage stamps and banknotes in 1918 for the newly-formed Republic of Czechoslovakia.

His work is suffused with his utopian ideals and vision for a better world. For Mucha, art was for all. He believed in the power of art to make the world kinder and more beautiful. Such was the popularity of his posters that people removed them as soon as they were put up, to keep for themselves.

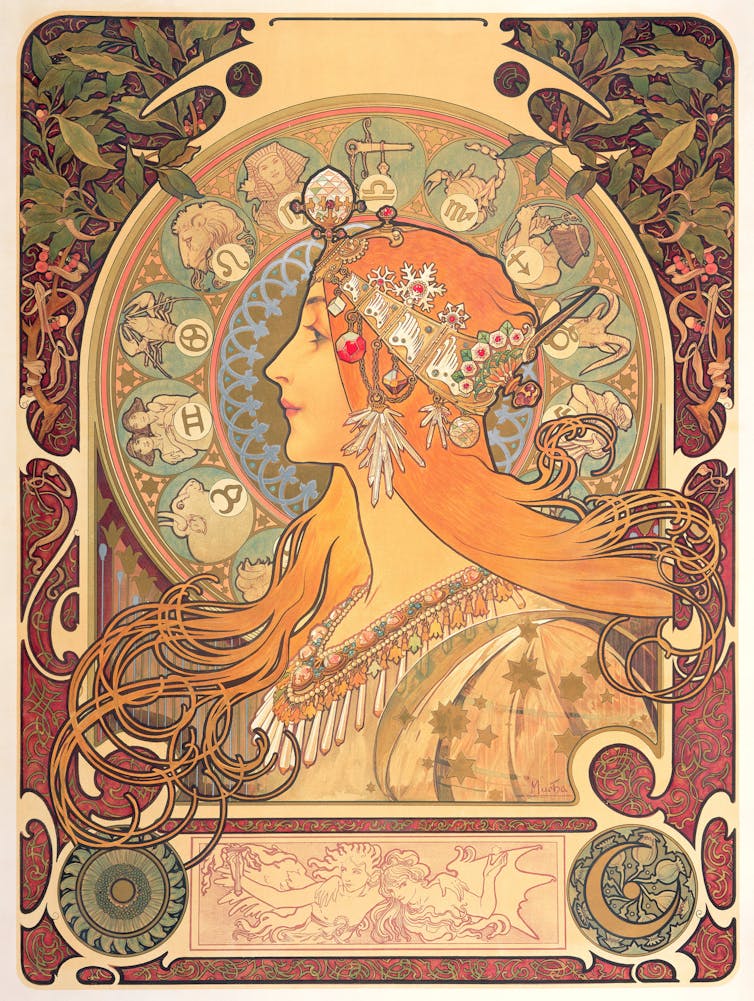

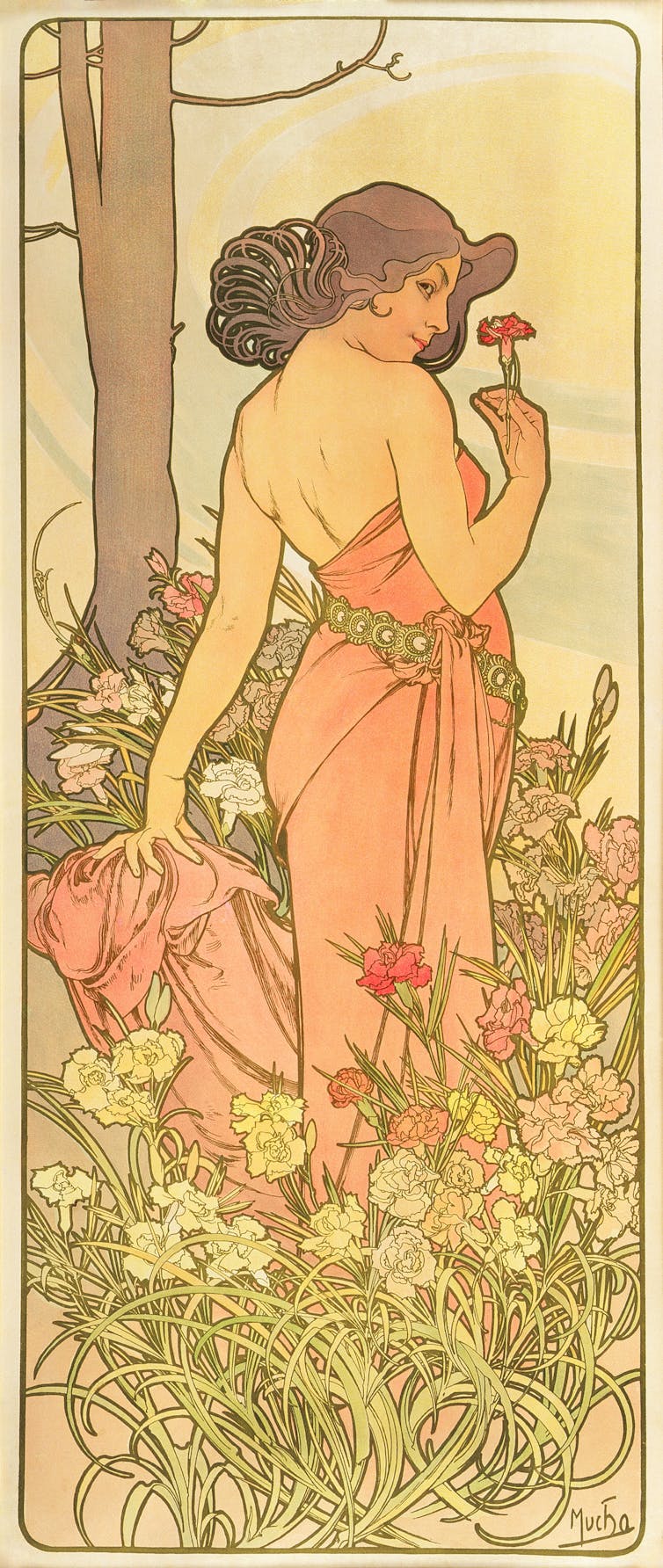

His works define the Art Nouveau (“new art”) style of the late 1800s, full of dynamic natural forms or shapes. The vines and flowers that decorate and frame Mucha’s artworks are also found in art, architecture and interior design.

To compose these works, Mucha used photographs of models as figure studies, which fill a wall of the exhibition. These photographs include Mucha himself posing with his daughter Jaroslava, a frequent collaborator and artist in her own right.

Celebrity and brand development

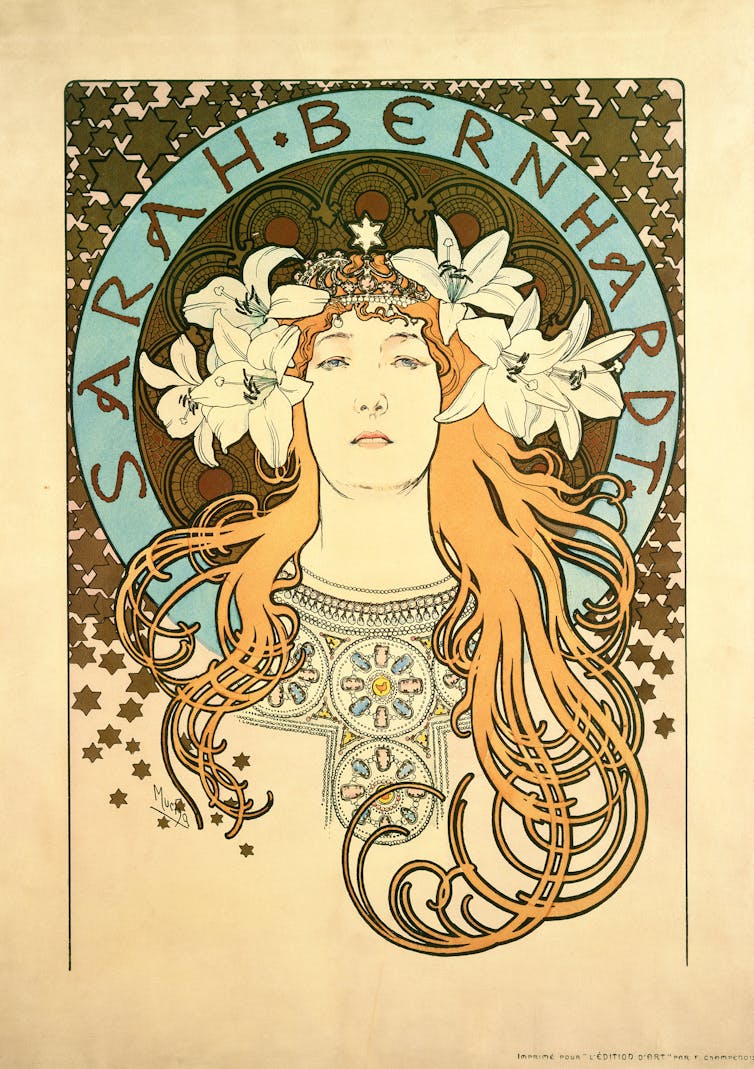

After the internationally-renowned actor the “Divine” Sarah Bernhardt, commissioned Mucha for a last-minute poster design, his own celebrity increased. Mucha began work on the poster for Bernhardt’s play, Gismonda, on Boxing Day 1894, and it was ready by New Year’s Day 1895. So began a fruitful relationship between the two.

Photo © Art Gallery of New South Wales, Diana Panuccio

Bernhardt, herself a sculptor, was rendered in larger-than-life sized posters for many of her plays, which convey the drama and tragedy of her performances, including roles as Hamlet and Lorenzo de’ Medici. When Bernhardt saw the Gismonda poster, she declared “You have made me immortal”.

Adjacent to these images conveying the glamour of celebrity and consumerism, the exhibition includes several works that highlight Mucha’s engagement with spirituality, Freemasonry and mysticism.

A curious juxtaposition in another room shows Mucha’s involvement with advertising alongside his famous rendering of seasons or artforms as allegorical figures. Where series of richly-decorated images show beautiful young women with glistening gold and silver, the largest and most eye-catching work is an advertisement for Nestlé.

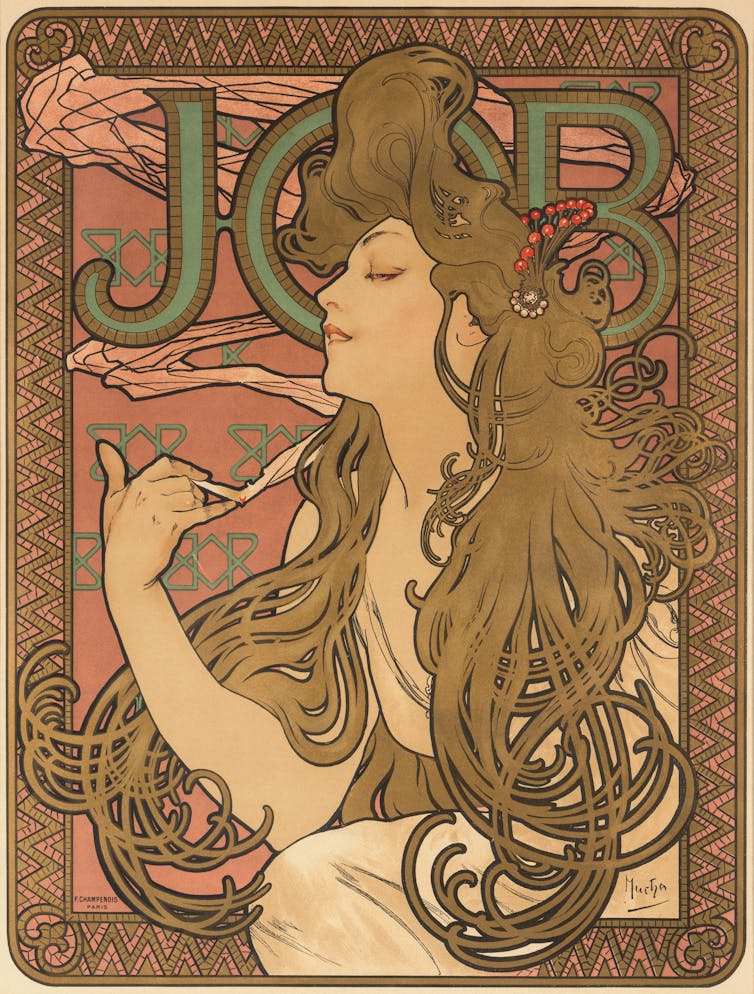

By depicting lissom women in a recognisable style, products grabbed attention without necessarily being depicted, as with JOB cigarettes or Moët & Chandon.

The Slav epic and national pride

Since his teen years, Mucha had a sense of patriotism, expressed first through amateur dramatics and later through his artworks.

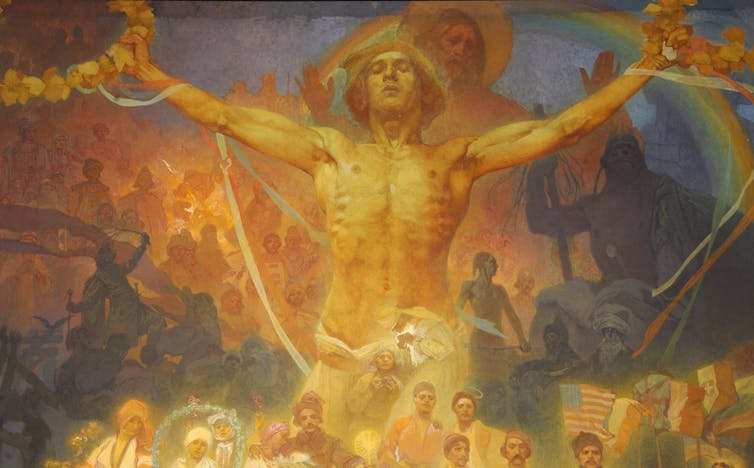

This patriotic fervour is best encapsulated in the monumental Slav Epic, 20 canvases tracing pivotal episodes in Slavic history. The work was intended to educate and inspire the Slavic people to build a peaceful future and learn from their past. It is crowned with a golden Christ-like figure to embody the new republic.

Given the fragility of the Slav Epic works to travel beyond their current home in the town of Moravský Krumlov, the Art Gallery of New South Wales instead provides digital projections set to music.

It offers a chance to experience the grandeur of the works, the richness of the colours and imagery, all treated with Mucha’s eye for detail.

A final display shows both the links to Japanese art in Mucha’s works and the broader taste for Japonisme during the late 1800s. The same influence is seen beyond this exhibition in Toulouse-Lautrec’s posters, with their use of flowing black lines or a limited palette. There are also manga, showing the legacy of Mucha’s artworks now reflected back in Japanese art and album covers. Groups like The Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane reproduced or appropriated Mucha posters, drawing on their iconic status and melding it with a psychedelic sensibility.

© Mucha Trust 2024

This exhibition offers more than just beautiful things. It provide the viewer with a glimpse of art that uplifts, and a balm for a world in upheaval, as it did 100 years ago.

Alphonse Mucha: Spirit of Art Nouveau is at the Art Gallery of New South Wales until September 22.

![]()

Will Visconti does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Alphonse Mucha and Art Nouveau: 100 years after its creation, his work is still a balm for a world in upheaval – tag:theconversation.com,2011:article/230674