Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Will McCallum, PhD Candidate – School of Communication and Creative Arts, Deakin University

Earlier this year, Opposition Leader Peter Dutton accused Prime Minister Anthony Albanese of not supporting Operation Sovereign Borders – the military-led border security operation that has “closed Australia’s borders to unauthorised maritime arrivals”.

It’s a proven line of attack from the Coalition, who claimed to have “stopped the boats” – almost all of which originate from Indonesia – during their tenure. The trope of a northern coastline in need of protection from a foreign “other” has resonated with many Australians for some time.

In the course of producing Waŋgany Mala (2024) – a documentary made in collaboration with Anindilyakwa and Gumatj people in northeast Arnhem Land – we learned that many First Nations peoples don’t typically subscribe to a land-sea distinction.

Instead, the land-seascape is crisscrossed with songlines that transcend this division. Margo Neale and Lynne Kelly, authors of the book Songlines: The Power and Promise, explain that songlines can act as navigational paths in the cartographic sense – but more fundamentally they encode knowledge of country, art and ceremony that is shared across generations.

Furthermore, the Knowledge Holders with whom we worked celebrated the time when boats from across the Indonesian archipelago weren’t intercepted.The precolonial ‘Makassan’ tale

Just three weeks after ousting his predecessor Scott Morrison, Albanese became the first prime minister to visit Indonesia’s third-largest city, Makassar, in South Sulawesi.

Albanese made reference to the so-called Makassan seafarers who set off for Australia from Sulawesi, the Aru Islands, West Timor and Rote Island.

These seafarers would spend up to six months of the year harvesting trepang (sea cucumber) alongside people in northeast Arnhem Land (a land they called Marege’) and the Kimberly (Kai Jawa). Their highly valuable catch would eventually reach the dinner tables of China’s Qing dynasty.

More than 600 or so years before European colonies were established on the continent, the Makassans created a language with First Nations peoples, they traded tools and other goods, they intermarried, and as a recent ABC Compass episode showed, many Aboriginal people travelled across the Indonesian archipelago. Some stayed in Indonesia permanently.

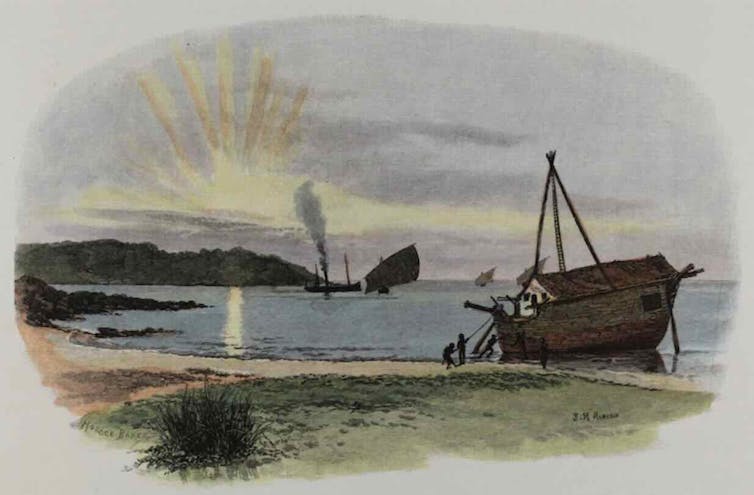

Library & Archives NT

The Makassan fleets were eventually taxed by the Australian colonial authorities, and then banned in 1907.

Over the past 100 years, the Timor and Arafura seas have become a literal and figurative space to be defended against boats transporting asylum seekers or illegal foreign fishing vessels.

But while the boats may no longer be arriving in Australia’s “exclusive economic zone”, stories of past connection and agency hold enormous value for local Nations.

Read more:

The stories of Australia’s Muslim Anzacs have long been forgotten. It’s time we honour them

Pride and agency

“Makassans were good to us […] it was a good time because the Aboriginal people weren’t angry, and the Makassans were happy,” says Edith Mamarika, an Indigenous Knowledge Holder and Anindilyakwa elder.

Mamarika is one of the oldest people living on Groote Eylandt, the largest island in the Gulf of Carpentaria. She never met Makassans, but her relatives did, and she knows the fishers were only given permission to stay at the beach after exchange and agreement was secured.

She shared her stories with us as we documented the construction of a traditional Indonesian sailing vessel, or pinisi, filming in Tana Beru all the way from the early selection of hardwood, to its eventual maiden voyage to Makassar.

The documentation shows the resilience of these UNESCO-recognised boat-building techniques. As we filmed, however, a more important story emerged: the experience of one of the building crew, Nirmala Syarfuddin Baco.

Today’s Makassans

Nirmala was born in Ambon, Maluku, but was forced to flee as a child during religious violence in 1999.

Her family settled in Baubau, southeast Sulawesi, but she eventually landed in Makassar where she studied marine science, inspired by her father who had spent much of his life assisting the Indonesian navy in stopping people from fishing using explosives.

Twenty-nine years old, fervently religious and the only woman in the boat-building and sailing crew, Nirmala has a challenging experience.

Her role is to manage finances and equipment deliveries, but she is invariably tasked with jobs such as preparing coffee or lunch for the crew. She also endures regular “playful” suggestions about sleeping arrangements once the boat is on the water.

Mala is fascinated by the histories shared by Edith Mamarika and other Knowledge Holders, and has ambitions to sail the new pinisi into Australian waters.

Amplifying older stories

What makes the Makassan story so compelling for a filmmaker is how it collides and competes with Australia’s more popular origin story: one of British explorers on tall sailing ships making “first contact”.

That is just one part of Australia’s story, and there are many more that could be amplified. Across northeast Arnhem Land there are very old stories about Indonesian men and women who have left an indelible mark on Country.

As Gumatj leader and Bawaka homelands custodian Timmy Djawaburarrwanga says at the end of our film: “my feeling is that this land always will be for Indonesians”.

Waŋgany Mala will be screened in Australia and Europe later this year.

![]()

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Long before politicians called to ‘stop the boats’, First Nations people welcomed arrivals from Indonesia – https://theconversation.com/long-before-politicians-called-to-stop-the-boats-first-nations-people-welcomed-arrivals-from-indonesia-228614