Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Alasdair Macintyre, Associate lecturer visual arts, artist, PhD, Australian Catholic University

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains the name of someone who has died.

In the late 1970s, the south bank of the Brisbane river was a hectic construction zone, the new and permanent home of the Queensland Art Gallery. At this same time, Judy Watson’s fledgling career as a visual artist was also beginning.

It is fitting that Watson’s expansive survey show, mudunama kundana wandaraba jarribirri (“tomorrow the tree grows stronger”, taken from a poem by Watson’s son Otis Carmichael), is staged in the Queensland Art Gallery building, which this year celebrates its 42nd birthday.

Contemporary photographs of the Robin Gibson-designed building on opening day in 1982 show a stark, sun-soaked edifice with small spindly trees on a sparse verge overlooking the river. The history of Watson’s considerable creative practice through the decades align with the gallery building.

Like the gallery, Watson is as much a part of the cultural fabric of Brisbane’s visual arts scene from the late 20th century into the new millennium. Her work is held in many public and private collections, both in Australia and internationally, most notably in the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Tate Gallery in London.

Originally trained as a printmaker, Watson is now truly a multimedia artist. The 130 artworks within this survey show include prints, drawings, paintings, video and installations spanning her career between 1981 to 2023.

Read more:

Here’s looking at: black ground, 1989 by Judy Watson

‘Rattling the bones of the museum’

Born in 1959 in Mundubbera and raised in Brisbane’s outer-suburban Acacia Ridge, Watson undertook her initial visual art training in Toowoomba before leaving Queensland to work and study interstate, and then overseas.

Watson’s matrilineal family is from Waanyi country in north-west Queensland, and this bloodline is a principal driving force of her art practice.

In this exhibition works are arranged into thematic categories; identity, ecology, feminism, and Watson’s investigations into historical and social archives.

Challenging notions of Indigenous aesthetic perspectives, Watson has spoken in the past about bringing hidden histories to light through delving into archives (“rattling the bones of the museum”, as she puts it).

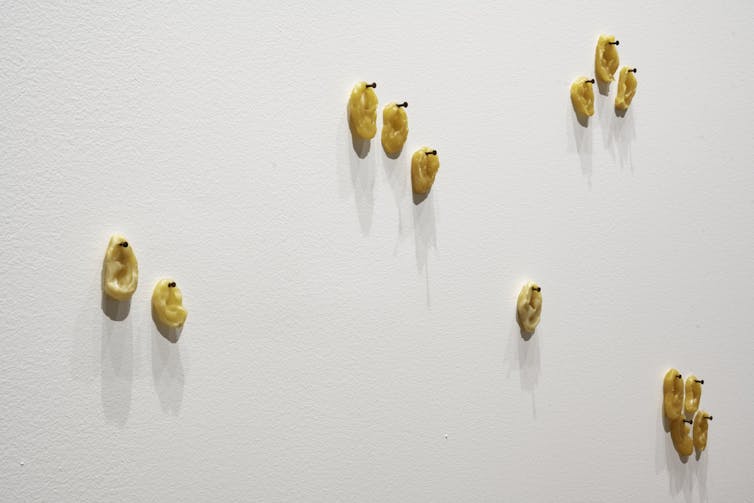

One such work is 40 pairs of blackfellow’s ears, lawn hill station (2008) which sees 40 pairs of cast beeswax ears nailed to the gallery wall, echoing the 19th century grisly punishment and murder of the Waanyi peoples by a brutal cattle station boss.

A more contemporary event, the demise of Palm Island man Cameron Mulrunji Doomadgee is also explored in memory bones (2007), a print work which Watson describes for her is “internal grieving” where white rib-like forms float above a blood-like splatter of red ochre.

Beauty and power

In the 1990s, Watson won the Moet and Chandon travelling fellowship, the second Indigenous artist to do so, after fellow Queenslander Gordon Bennett. Unlike Bennett, whose “in ya face” work was overtly socio-political, Watson’s approach is more subtle.

In the Louise Martin-Chew’s 2009 book about Judy Watson, Blood Language, Watson described how her work aims to seduce the viewer through its beauty. Powerful messages of Indigenous dislocation, Stolen Generations, and disenfranchisement lie beneath.

There are monumental works that fill the gallery walls. In canyon (1997) we see a two-storey high thin vertical canvas with a snaking skein of yellow ochre. In two halves with bailer shell (2002), the shells used to bail water out of a canoe, are rendered in thin white lines over a sumptuous ocean-blue.

The deep pigments within Watson’s works – particularly the indigo blues and ochres – are intense and beguiling. Printed or digital reproductions do not do them justice: these works must be seen in the flesh.

Several sculptural works broaden Watson’s practice, with walama (2000) a large installation of bronze termite mounds and upside-down dillybags, and her wonderful toe row (2016), a cast bronze fishing net permanently installed outside the gallery.

Over the course of four decades, those spindly trees bordering the Queensland Art Gallery now tower over the riverbank, offering welcome shade to visitors and forging a connection between the gallery and the river.

Like those mighty trees, Watson’s career has grown in a similar manner in that time: strong, resolute and uncompromising. This survey exhibition offers a counterpoint to the online world of glib fast-art purveyors that feed the insatiable appetite of social media consumers.

Watson is an artist of the highest integrity, a living legend of Australian art, her people, and country. Tomorrow the Watson tree will indeed continue to grow stronger.

mudunama kundana wandaraba jarribirri: Judy Watson is at the Queensland Art Gallery until August 11.

![]()

Alasdair Macintyre does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Strong, resolute and uncompromising: you should see the intense and beguiling art of Waanyi artist Judy Watson – https://theconversation.com/strong-resolute-and-uncompromising-you-should-see-the-intense-and-beguiling-art-of-waanyi-artist-judy-watson-226008