Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Lisa J. Hackett, Lecturer, University of New England

For many the wedding gown is the most expensive item of clothing they will ever own, and it has significant emotional and social value.

The recent case of a Queensland woman allegedly scamming brides out of their wedding dresses on the pretext of dry-cleaning no doubt bought distress to their owners and, given the average price of a wedding dress today (A$2,385), 70 cases of wedding dress theft could be lucrative.

The average cost of an Australian wedding is A$36,000. Despite many Australians forgoing a religious ceremony, declaring your love in front of friends and family remains an important social ritual – and the dress is often the most important consideration.

A brief history

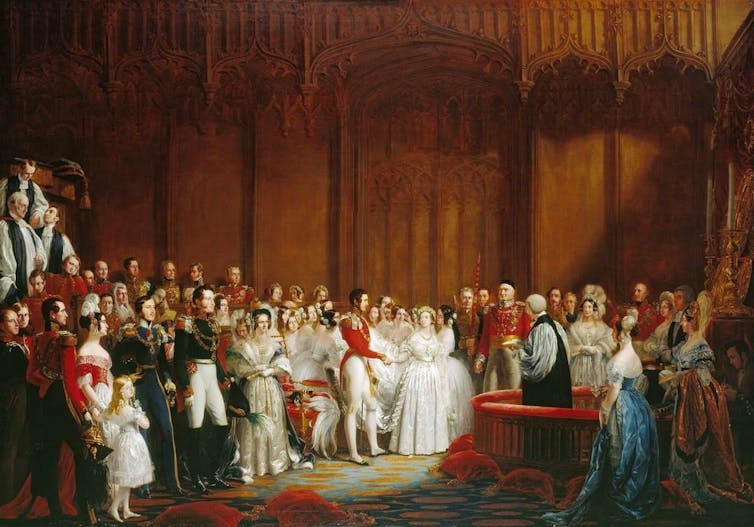

The modern history of the wedding dress in Australia is closely linked to Queen Victoria. Her 1840 dress became the “quintessential wedding dress”.

Victoria’s white dress featured an eight-piece bodice with a wide, open neckline with short and puffed off-the-shoulder sleeves and a pointed waistline. The neckline and sleeves were trimmed with lace and the floor-length skirt was full, with forward-facing pleats.

Wikimedia Commons

Read more:

The wedding dress: from Queen Victoria to the heights of fashion

Prior to Victoria, the wearing of white signalled the bride was poor and without a dowry. In the 16th and 17th centuries brides would often wear pale green, symbolising fertility.

From the 19th century, white wedding dresses had been worn by wealthy and royal brides, but for royal brides the dresses were often completely covered in silver and gold threads. Victoria rejected the embellishment and did not wear the red ermine robe of state, wanting to be seen as a wife rather than queen.

Most 19th century brides wore a dress they could wear again and popular colours were russet, brown, grey or lilac.

State Library Victoria

As white gowns became increasingly popular they began to be seen as symbols of purity and innocence because of the religious association of these colours.

The association of white with innocence in the popular imagination affected the wedding gown decisions of women who were not marrying for the first time. Widows remarrying in the Victorian era didn’t wear white and didn’t wear a veil. They might wear pearl or lavender dresses trimmed with ostrich feathers.

State Library of South Australia

Over the 20th century, white wedding dresses became increasingly popular. Brides were no longer wearing their “Sunday best”, and the tradition of buying a unique bridal gown became established. By the turn of the 21st century, historian Christyana Bambacas found wedding planning had become the reserve of the bride and the white gown had become the central artefact, positioning “the bride as star of this public ritual”.

Australian brides often have highly emotional connections to their wedding gowns. Research into discussions on online wedding forums found brides-to-be used phrases such as “my love for my dress grew” and being “in love with” their gowns. The gown represents the bride’s idealised self – even if the event is temporary.

The tradition of keeping the dress a well-kept secret stems from 18th century arranged marriages, when it was believed to be “unlucky” for the groom to see the brides, lest he pull out of the wedding. The anticipation of the reveal of Kate Middleton’s wedding dress, where even the name of the designers was kept secret, reflects this ritual.

Something old

Unlike couture or historical garments, wedding gowns are familiar. They are common to the human experience, and yet unique to each bride.

Wearing your mother’s or grandmother’s wedding gown is becoming increasingly popular. Princess Beatrice was married in a gown designed by Norman Hartnell for her grandmother, Queen Elizabeth II, in the 1960s.

With just a few adjustments, brides are able to update vintage gowns to give them a modern twist.

Two-thirds of Australian brides keep their dress, many in the hope daughters or granddaughters will wear it. This suggests that, despite the increasing number of people choosing to not get married, weddings remain an important cultural ritual.

Some women keep their dress to be buried in. Others donate their wedding dresses to be made into Angel gowns to bury stillborn babies, the dress taking on new meaning for grieving families.

The end of the big wedding

The average age of first marriage in Australia has risen from 23-years-old for men and 20-years-old for women in 1970 to around 30 today.

The current cost-of-living and housing crises has seen couples cut back on their wedding expenditure, with impacts particularly felt by wedding gown businesses at the luxury end of the market.

Regardless of rising divorce rates, and generational shift in attitudes to marriage (43% of 18-39 year olds believe it is an outdated institution), marriage is considered a one-off life event.

State Library of South Australia

The wedding dress is an indulgence driven by social norms and emotions where the bride is often balancing tradition with individuality.

While films, fashion, bridal magazines and celebrity weddings continue to perpetuate the fantasy and emotion embedded in the wedding dress, the dress continues to be a poignant part of our social lives.

Of all the clothes we own, the wedding dress is the one most treasured, as a reminder of what it symbolised, its aspirations or as a family heirloom – making its loss even more distressing.

![]()

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. A Queensland woman allegedly stole 70 wedding dresses. Here’s why the white gown is worth much more than its price tag – https://theconversation.com/a-queensland-woman-allegedly-stole-70-wedding-dresses-heres-why-the-white-gown-is-worth-much-more-than-its-price-tag-220657