Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Rebecca Banham, Postdoctoral fellow, University of Tasmania

Shutterstock

The famous Sycamore Gap tree was felled last week, prompting global expressions of sorrow, anger and horror. For some, the reaction was puzzling. Wasn’t it just a single tree in northern England? But for many, the tree felt profoundly important. Its loss felt like a form of grief.

Trees tell us something important about ourselves and who we are in the world. That is, they contribute to ontological security – our sense of trust that the world and our selves are stable and predictable.

Trees – especially those celebrated like England’s sycamore or Tasmania’s 350-year-old El Grande mountain ash – feel like they are stable and unchanging in a world where change is constant. Their loss can destabilise us.

What makes a tree iconic?

Individual trees can become important to us for many reasons.

When the wandering ascetic Siddhartha Gautama sat at the foot of a sacred fig around 500 BCE, he achieved the enlightenment which would, a few centuries later, lead to his fame as the Buddha. This sacred fig would become known as the Bodhi Tree. One of its descendants attracts millions of pilgrims every year.

Globe Trotting/Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND

Sometimes a tree becomes iconic because of its association with pop culture. U2’s hit 1987 album The Joshua Tree has inspired fans to seek out the tree on the cover in the United States’ arid southwest – a potentially dangerous trip.

Other trees become famous because they’re exceptional in some way. The location of the world’s tallest tree – a 115-metre high redwood known as Hyperion – is kept secret for its protection.

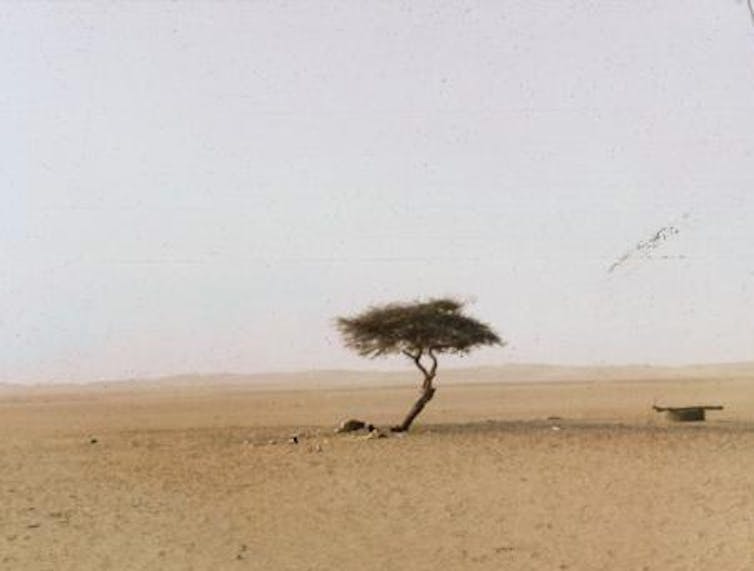

Niger’s Tree of Ténéré was known as the world’s most isolated, eking out an existence in the Sahara before the lonely acacia was accidentally knocked down by a truck driver in 1973. Its site is marked by a sculpture.

Michel Mazeau/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

In 2003, the mountain ash known as El Grande – then the world’s largest flowering plant – was accidentally killed in a burn conducted by Forestry Tasmania. The death of the enormous tree – 87 metres tall, with a 19 metre girth – drew “national and international” media attention.

This year, vandals damaged a birthing tree sacred to the local Djab Wurrung people amidst conflicts about proposed road works in western Victoria.

And in 2006, someone poisoned Queensland’s Tree of Knowledge – a 200-year-old ghost gum famous for its connection to the birth of trade unionism in Australia. Under its limbs, shearers organised and marched for better conditions. The dead tree has been preserved in a memorial.

What is it to lose a tree?

Sociologist Anthony Giddens defines ontological security as a “sense of continuity and order in events”.

To sustain it, we seek out feelings of safety, trust, and reassurance by engaging with comfortable and familiar objects, beings and people around us – especially those important to our self-identity.

When there is an abrupt change, it challenges us. If your favourite tree in your street or garden dies, you mourn it – and what it gave you. But we mourn at a distance too – the Sycamore Gap tree was world-famous, even if you never saw it in real life.

In my research, I have explored how Tasmanian forests – including iconic landscapes and individual trees – can give us that sense of security we all seek in ourselves.

As one interviewee, Leon, told me:

These places should be left alone, because in 10,000 years they could still be there. Obviously I won’t be, we won’t be, but perhaps [the forest will be].

Temporality matters here. That is, we know what to expect by looking to the past and imagining what the future could be. Trees – especially ancient ones – act as a living link between the past, present, and future.

As my interviewee Catherine said:

You lie under an old myrtle and you just go, ‘wow – so what have you seen in your lifetime?’ Shitloads more than me.

That’s why the loss of the Sycamore Gap tree has upset seemingly the entire United Kingdom. The tree was famous for its appearance: a solitary tree in a photogenic dip in the landscape.

Its loss means a different future for those who knew it. It’s as if you were reading a book you know – but someone changed the ending.

Read more:

Sycamore Gap: what the long life of a single tree can tell us about centuries of change

Loss of connection

We respond very differently when humans do the damage compared to natural processes. In one study, UK homeowners found it harder to accept their house being burgled than for it to be flooded, seeing flooding as more natural and thus less of a blow to their sense of security.

This is partly why the sycamore’s death hurt. It didn’t fall in a storm. It was cut down deliberately – something that wasn’t supposed to happen.

The sycamore was just a tree. But it was also not just a tree – it was far more, for many of us. It’s more than okay to talk about what this does to us – about how the loss of this thread of connection makes us grieve.

Yes, we have lost the Sycamore Gap tree, just as we lost El Grande and many others. It is useful to talk about this – and to remember the many other beautiful and important trees that live on.

Read more:

Photos from the field: capturing the grandeur and heartbreak of Tasmania’s giant trees

![]()

Rebecca Banham received funding from an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship, which funded the research associated with this article.

– ref. It wasn’t just a tree: why it feels so bad to lose the iconic Sycamore Gap tree and others like it – https://theconversation.com/it-wasnt-just-a-tree-why-it-feels-so-bad-to-lose-the-iconic-sycamore-gap-tree-and-others-like-it-214841