Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Catherine Speck, Emerita Professor, Art History and Curatorship, University of Adelaide

Milton Moon (1926-2019) was not your regular potter. He was deeply imbued with Zen Buddhism and once said each vessel is a container for thoughts, “a fundamental expression of life’s forces”.

His work produced over six decades is on show in a new exhibition at the Art Gallery of South Australia that calls for close looking.

He took to his craft in his early 30s from the base of a successful career in ABC radio.

Once his hands were working with clay, he never looked back.

On show are some of his earliest ceramics, made and exhibited in 1959 when living in Brisbane. His influences were artists living or showing in Brisbane then, including David Boyd, son of Merric Boyd, and Hermia Boyd whose studio ceramics were on show in July 1959 at the progressive Johnstone Gallery.

Studio ceramics – with its hallmark folk tradition, figurative form and applied decoration – appears briefly in some early Moon work such as his Sculptural vase, 1960. Owl-like, the eyes at the top look down on viewers, while the decorative markings double as plumage and drawing on clay.

More elemental even, but in the same style, is his Antipodean head, 1962, whose rough torso looks hewn from a rock-face.

The art of Zen

While the earthy nature of some of Moon’s pots are in response to the Australian landscape, he had a deep interest in matters philosophical, formally studying philosophy in the mid-1960s. This was greatly extended by a year in Japan in 1974.

It wrought changes to Moon himself. He studied meditation in the Zen style with Kobori Nanrei Sōhaku, Abbot of the Rinzai sect, whose teachings influenced his life course, and his ceramics.

As Moon said, “no one ever leaves Japan unaltered”. In his 2006 book The Zen Master, the Potter and the Poet, he explores this journey.

On display are a series of ceramic landscape platters that point to those deep changes such as Plate with blossom pattern, 1978. Its abstract marks meld an Australian landscape base with finely drawn blossom, while the calligraphic gestures on his Dish, 1982, point to a deep infusion of a Zen way of thinking and making.

Read more:

Friday essay: how the West discovered the Buddha

A painterly potter

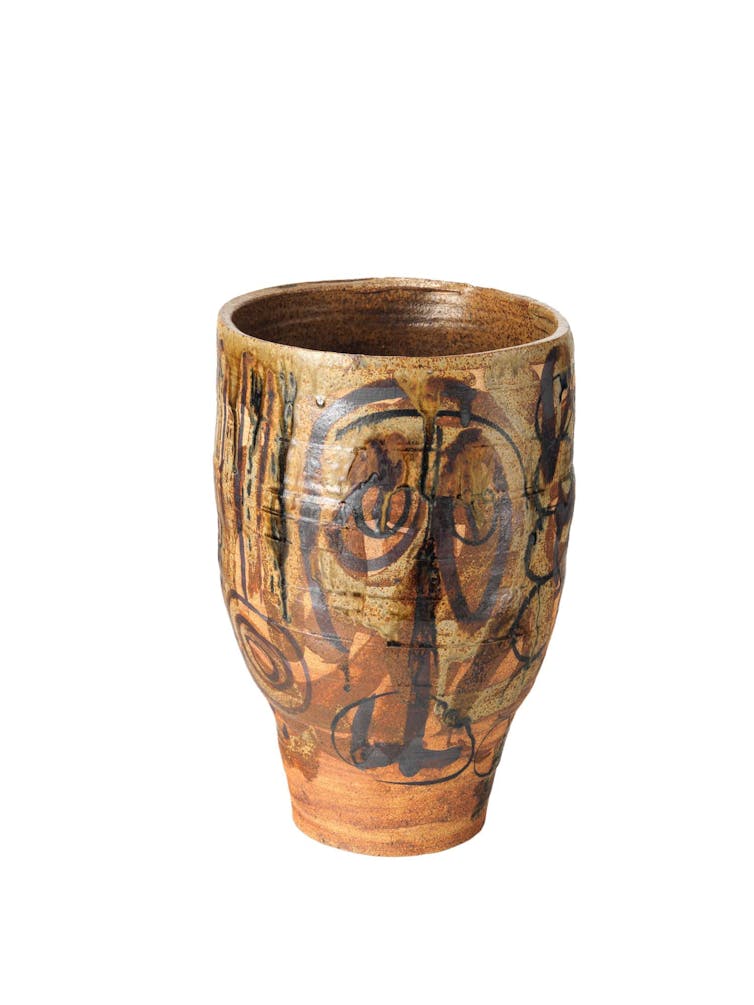

Moon was a painterly potter. He saw little difference between painting on a canvas and painting with glazes on the surface of a pot, and two of his abstract paintings, mark making on canvas, are in the exhibition.

Moon’s delicate, refined Fairweather pot, 1966, made in homage to his friend Ian Fairweather, is very much a painted pot. Its calligraphic lines, inspired by the artist’s paintings, sweep around and down the rounded pot with grace and beauty.

Moon, though, observed at the time “it is difficult to achieve the fragility and impermanence Fairweather gives his paintings”.

Some ceramic pieces are functional. Others, like the early 1970s Folded pot, have their functionality denied.

The allure lies in the harmony of the shape, the gradation of glazes, and its changing texture governed by a sense of restraint: not too much, not too little.

‘Let nature take its course’

Moon was fascinated by the geological nature of clay itself.

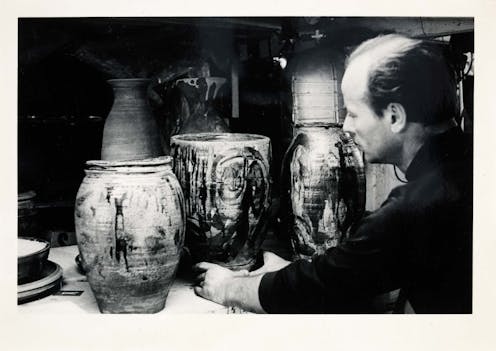

What stands out is the texture of much of the work on show such as his Platter, 1962-64, which Moon achieved by the quality of the clay he used, his mode of firing the pots and his innovative application of glazes. The word “experimentation” comes to mind.

In the accompanying catalogue, his son Damon (also a master potter), talks about the technical aspects of his father’s work and how he applied glazes to clay like an artist – drawing or painting onto the surface with a brush, a stick or his fingers, scratching back layers of oxides and adding wood ash to achieve the colours and textures of the landscape he was after.

The quirks in the firing process were yet another element in Milton Moon’s experimentation, Damon observing:

in this funny business of mud and water and fire, he was willing to let nature take its course. I think he liked that aspect of ceramics.

Hybrid space

While the curatorial intent in Crafting Modernism is to contextualise Milton Moon’s ceramics in the broader narrative of Australian art, his location in that narrative is more complex.

This stands out when looking at his impressively large floor pots such as his Yourambulla landscape pot, 1990, standing close on a metre high with its earthy tones, and inscribed, scratched-in lines to convey the dense scrubby nature of the bush.

Over and above the obvious references to the landscape is an underlying sense of the calligraphic gestures to evoke the bush.

In this and many other works he dances between two worlds and two cultures, crafting a hybrid space. That is what is so alluring about his work.

Moon was a prolific potter. He spoke through his ceramics, once writing making marks on the surfaces of pots “are my words”; they are a “whispered secret”.

The beauty of the exhibition curated by Rebecca Evans is its distilling of his output over 60 years to a coherent and poetic display. Its framing in a white space, in a top-lit gallery with natural light augmented by artificial light, makes the works sing.

A Zen-Buddhist vision lives on in works of great beauty.

Milton Moon: Crafting Modernism is on display at the Art Gallery of South Australia until August 6.

Read more:

How Japanese avant-garde ceramicists have tested the limits of clay

![]()

Catherine Speck has, with Joanna Mendelssohn, Catherine De Lorenzo and Alison Inglis, received funding from the ARC to investigate exhibitions of Australian art.

– ref. Milton Moon: the Australian artist who brought a Zen Buddhist, modernist and painterly sensibility to pottery – https://theconversation.com/milton-moon-the-australian-artist-who-brought-a-zen-buddhist-modernist-and-painterly-sensibility-to-pottery-205480