Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

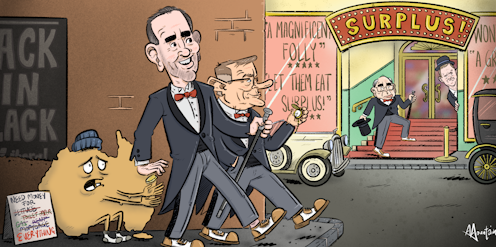

Wes Mountain

Surplus or not, the budget papers show us living through pretty awful times.

Living standards measured by the buying power of wages are set to go backwards in 2023-24 as wages are expected to grow by 3.75% while prices rise by 6%.

Separate figures released by the Bureau of Statistics as Treasurer Jim Chalmers was preparing to deliver his speech show the volume of goods and services bought from Australian retailers has shrunk for the past six months.

Living standards measured by gross domestic product are set to go backwards in 2023-24 as total GDP grows by an unusually low 1.5% while Australia’s population grows by 1.7%, producing a so-called “per capita recession”.

The good news on the government’s finances is largely historical.

The budget position for 2023-24 was improved by $42.15 billion because of measures largely outside the government’s control (so-called “parameter and other variations”).

Chief among these has been an unexpectedly big increase in the number of Australians in work and subject to income tax (as the unemployment rate has fallen to a half-century low), and much higher prices for exports than expected in the last budget (roughly twice as high in the case of iron ore), producing much higher profits to tax.

The government has chosen to spend just $12 billion of the $42.15 billion bounty, which has allowed the rest of the bounty to produce a (small) budget surplus of $4.2 billion in 2023-24.

After 2023-24, it will be deficits again for at least a decade on the budget’s projections, as the unusual circumstances that delivered the unexpected $42.15 billion fall away.

The unemployment rate is set to climb from its long-term low of 3.5% to 4.25% by mid next year and to 4.5% by mid-2025. The number of Australians in work and in the income tax system is expected to grow by just 1% in 2023-24 and 2024-25 after growing by 2.5% in 2022-23. The iron ore price is expected to halve within a year.

Government income is set to grow 8.8% in 2022-23 and 5.1% in 2023-24. After that, it is scheduled to barely grow in 2024-25, climbing just 0.5%, before returning to growth of 4.4% and 4.9 in 2025-26 and 2026-27.

Given that the costs of some government programs are expected to grow by a lot (the cost of National Disability Insurance Scheme is expected to grow by an average of 10.4% per year and the cost of funding hospitals by 6.5% per year), it looks as if the government is going to have to find more money.

Spending on defence is set to climb 22% over the next four years, and doubtless by more beyond, as spending on building and buying the nuclear-powered submarines under the AUKUS agreement ramps up.

Chalmers has sensibly abandoned the Coalition’s quaint commitment to keep the tax to GDP ratio to 23.9%, which is just as well because the influx of revenue scheduled for 2023-24 will to take it to 23.9% (25.9% including non-tax revenue) before it falls back.

Longer term, Chalmers will have to raise more tax or cut government services. The increases in the tax on large superannuation balances, tobacco excise and the petroleum resource rent tax are a sign of what’s to come.

The ultra-expensive Stage 3 income tax cuts deliver a hard-to-defend $2,000 per year to high earners on $120,000 per year. Although legislated back before COVID, they are not due to take effect until mid next year, meaning there’s still time (and another budget) in which to wind them back and reorientate them to Australians who need them more.

Where Chalmers has supported Australians hit by ultra-high inflation in this budget, he has tried to do it cheaply.

Boosting JobSeeker and related payments by the $128 per week Chalmers’s economic inclusion advisory committee wanted would have cost $5.7 billion per year. Instead, Chalmers will lift it by $20 per week (and slightly more for most Australians on it aged 55 and over) at a cost of $1.3 billion per year.

As important as extending parenting payments to single parents with children up to 14 years of age will be those who need it. The measure is budgeted to cost just half a billion per year.

Boosting Commonwealth rent assistance by up to $16 per week (the “largest increase in more than 30 years”, Chalmers says) will cost a tad more, around $700 million per year.

The cost of the energy package (which the treasurer says will take $500 per year off some power bills and three-quarters of a percentage point off inflation) is marked in the budget as “not for publication”, presumably in deference to negotiations with the states which will co-fund it.

Chalmers said during his press conference this budget had been much harder to put together than his first. What he could have added is that his next budget is shaping up to be even harder.

Economic growth has been revised down. So convinced are financial markets the economy is weakening, that ahead of the budget they were pricing in no further Reserve Bank interest rate increases in this year and one interest rate cut, by December.

The economic forecasts in the budget suggest the coming per-capital recession won’t turn into an actual recession. Economic growth is expected to climb from an ultra-low 1.5% in 2023-24 to a still-low 2.25% in 2024-25 and then to 2.75%.

Inflation, which was 7% in the year to March, is forecast to fall to 6% in the year to June, and then to a less-worrying 3.25% by June 2024.

Although the forecasts move in the right direction, they are not good. Chalmers said getting things right this time required a “fine balance”. Future budgets are shaping up to require just as much.

![]()

Peter Martin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Budgeting for difficult times is hard – just ask Jim Chalmers – https://theconversation.com/budgeting-for-difficult-times-is-hard-just-ask-jim-chalmers-205209