Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Brooke Nickel, NHMRC Emerging Leader Research Fellow, University of Sydney

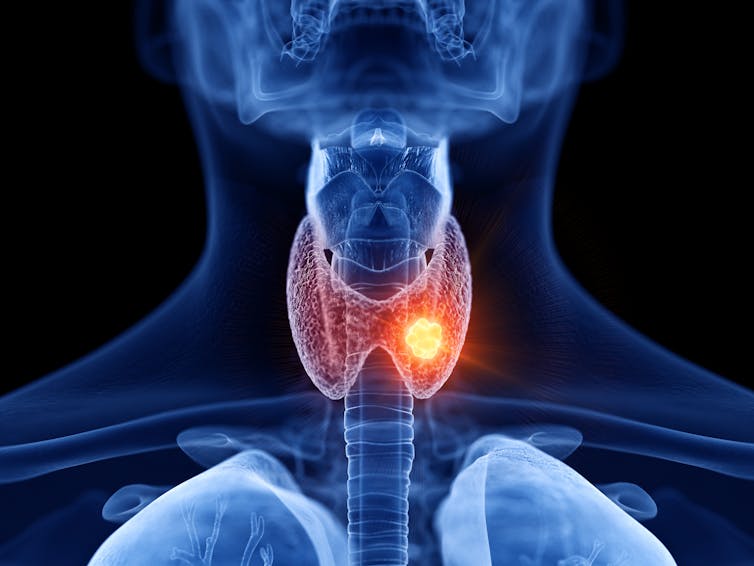

The thyroid is a gland located at the base of the neck. It makes thyroid hormones, which control the way the body uses energy.

A thyroid nodule is a solid or fluid-filled lump found within the thyroid. The majority of thyroid nodules are small, can’t be felt by touch and do not cause symptoms. They are caused by an overgrowth of cells in the thyroid gland. In a few people, the nodules grow and cause symptoms such as pressure, difficulty swallowing or breathing.

Thyroid nodules are very common, with more than half of people scanned show small nodules.

So, they might never cause problems are only discovered incidentally. But when should you follow up and get treatment?

Read more:

I’m approaching a ‘milestone’ birthday. What health checks should I have at my age?

Who gets them

Nodules tend to be more commonly detected in women, at three times the rate seen in men. The incidence also increases with age.

At age 30 it is estimated around 30% of women will have a nodule. By age 70, approximately 70% of women will have at least one. The risk of a thyroid nodule is also higher if you have other thyroid conditions such as Hashimoto’s disease or have been exposed to radiation. However, only a very small proportion of the adult population will need treatment or review for nodules.

People often find out that they have thyroid nodules during a routine check-up or when investigating another unrelated health issue. Thyroid nodules are readily seen on common imaging tests such as an ultrasound or CT scans. Because there is rapidly growing access to and use of clinical imaging, and also, we tend to visit the doctors a lot more as we age, the chances of incidentally finding thyroid nodules has increased.

Shutterstock

When should you worry?

Understandably, people worry a thyroid nodule might mean cancer. But we now know around 10% of patients with thyroid nodules harbour cancer – so approximately 90% of those detected don’t pose a cancer risk.

Generally, the risk is only increased with past radiation exposure, a family history of thyroid cancer, obesity, or if aged younger than 20 at the time of discovery of the nodule. Symptoms of concern are: an enlarging thyroid nodule, recent onset of hoarseness, difficult swallowing, neck pain or discomfort, large firm nodule or surrounding enlarged lymph nodes.

Your medical history and any physical symptoms related to the thyroid should always been discussed with a doctor. They may recommend further investigation, or to watch for changes over time. The idea of observing may sound counter-intuitive, but it can be important because doing further investigations may not always be in your best interest.

Treatment for thyroid nodules depends on whether the nodule is suspected of being a cancer or is causing symptoms, such as neck discomfort or an overproduction of thyroid hormones. Often, there will be no formal treatment required for thyroid nodules.

Read more:

29,000 cancers overdiagnosed in Australia in a single year

When detection leads to poorer health

There is an important problem that exists with “incidentally” found thyroid nodules.

In recent decades, the dramatic increase in new cases of thyroid cancer has largely been driven by findings of small, low-risk thyroid cancers; found when investigating thyroid nodules. Strong evidence exists overdiagnosis – that is, a correct but unnecessary diagnosis – accounts for a large proportion of thyroid cancer cases.

We know that despite a rapid increase in the diagnosis of thyroid cancer, the number of people who die from it (the mortality rate) has remained steady. This means most of these cancers are found unnecessarily. And finding them can cause worry and sometimes lead to treatments and financial costs that ultimately may not have been necessary at all.

Overdiagnosis and subsequent overtreatment of this condition has been extensively documented. But working out how to avoid and address these issues remains difficult. The American Thyroid Association is a leading treatment group for the management of thyroid nodules. It recommends nodules smaller than 1 centimetre should not be routinely biopsied. In line with this, systems for ultrasound reporting have been introduced to reduce overtreatment of small thyroid nodules.

In 2020, we conducted community research and found Australians were unaware of the harms of overdiagnosing low-risk thyroid cancers. They wanted more community education and supported the idea of clinical guidelines to minimise over-investigating and over-treating low-risk conditions.

Shutterstock

Take-home advice

While there is a small proportion of thyroid nodules that cause harm, the large majority are found incidentally and are unlikely to cause further problems.

Investigating and treating these nodules can lead to unwarranted physical, psychological and financial consequences including overdiagnosis, overtreatment, anxiety and out-of-pocket costs.

It is important to be aware of the issues involved in finding a thyroid nodule, and ask questions – for ourselves and our loved ones – about what this means and whether further investigation or treatment is really needed.

![]()

Brooke Nickel receives Fellowship funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC).

Anthony Glover receives funding from Cancer Institute NSW.

Patti Shih’s research projects are funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC)

Anna Story does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. My scan shows I have thyroid nodules. Should I be worried? – https://theconversation.com/my-scan-shows-i-have-thyroid-nodules-should-i-be-worried-203245