Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Renée Middlemost, Lecturer, Communication and Media, University of Wollongong

IMDB

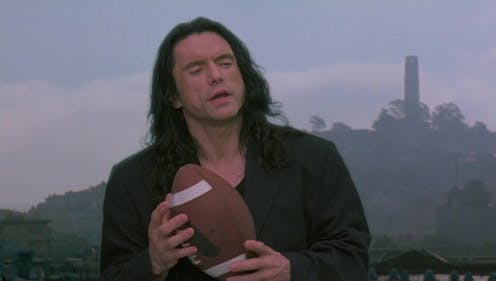

A jaunty yet dramatic piano-driven soundtrack motif; a view of the Golden Gate Bridge; a series of location shots around San Francisco. The generic title sequence of the 2003 film The Room barely hints at what follows.

The Room is a straightforward melodrama centred around a love triangle between Johnny (Tommy Wiseau, who also directs), Lisa (Juliette Danielle) and Mark (Greg Sestero). Described as “the worst movie ever made”, it continues to draw sellout crowds worldwide.

One might rightfully wonder: what is the ongoing appeal of a film dubbed “the Citizen Kane of bad films” 20 years on?

Cult audiences

Scholars have debated the key features of cult film for decades, with poor quality (narrative, aesthetic or both), quotable dialogue, word-of-mouth spread and box-office failure all cited.

Most agree an adoring audience is vital to maintaining cult status. The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1972) is the most recognisable example of a cult film, distinguished not by its content but by the devotion of an audience “beyond all reason”.

The Room follows this tradition. Wiseau self-funded the film, a gigantic billboard of his face in Los Angeles, and a two-week run of screenings at the Laemmle Fairfax and Fallbrook Theatres in June 2003.

Word of mouth quickly spread among film fans, attracted by dire reviews such as “watching this film is like getting stabbed in the head”.

The poor reviews inspired new fans, who would come along and shout at the film, lip-sync the worst lines and throw spoons at the screen – a reference to the stock images of spoons that appear as decor in Johnny and Lisa’s apartment. Celebrity fans followed, with actors Kristen Bell and Paul Rudd hosting private screenings.

Fan-driven demand led to the film’s eventual release on DVD in 2005, coinciding with the launch of YouTube.

Clip compilations focusing on the film’s so-bad-it’s-good credentials allowed those unable to attend cinema screenings to consume portions of the film.

Cinemas such as The Prince Charles in London provided “viewing guides” to costume-clad audiences, instructing audience members of what to call out (or throw) when. Most attendees brought their own spoons, demonstrating the ritualisation of the active audience response.

The audience response to The Room also points to a wilful misreading of Wiseau’s intent. The cult of The Room is distinguished by the “cruelty” of laughing at “an immigrant filmmaker’s misbegotten passion project”.

But perhaps it is Wiseau who is having the last laugh.

Read more:

Violent clowns and panto dames: the origins of Rocky Horror’s Frank-N-furter

Tommy Wiseau’s World

As I have argued elsewhere, the growing profile of The Room resulted in a shift to interest in Wiseau as a cult auteur – as the long legal stoush over unauthorised documentary Room Full of Spoons (2016) demonstrates.

While early interviews with Wiseau indicate his belief in the film’s quality, over time he has reframed his authorial intent and now claims the film is a comedy.

While we can never know Wiseau’s true intent, his reframing of the film’s reception is a fascinating part of its history, which anchors the narrative of its most well-known paratext: James Franco’s The Disaster Artist (2017), a comedy that follows Sestero (Dave Franco) and his friendship with Wiseau (James Franco) during the creation of the film.

Notably, Franco as Wiseau proclaims at the film’s fictional premiere:

I’m glad you like my comedic movie – exactly how I intended. I have vision for this movie.

The enduring cult

Sestero’s book The Disaster Artist (2013) and Franco’s adaptation describes the pair’s meeting, their unconventional friendship, and Wiseau’s aspirations for Hollywood acceptance.

Rather than a cruel “takedown” or exposé, the book documents Sestero’s affection for Wiseau, and despite the reviews, his fondness for the film that ultimately made his name.

Although initially a source of friction with Wiseau, he has grown to support Sestero’s book, referring to it as “the red bible” for its red cover seen clutched in the hands of fans during signings and appearances.

The film adaptation of The Disaster Artist arguably resulted in the attainment of Wiseau’s long-held desire for Hollywood credibility, with James Franco declaring the universality of the story: “In so many ways, Tommy c’est moi”.

The Disaster Artist was widely praised, and the film and Franco went on to win Golden Globe Awards in 2018.

There, the highlight for many was Wiseau’s appearance on stage during Franco’s acceptance speech. Perhaps Hollywood dreams can come true.

A better place

As The Room turns 20, I argue it is still beloved by audiences because we love an underdog.

The Room might be a “bad film”, but it’s also about pursuing our dreams.

As Wiseau says in the film:

You can love [something] deep inside your heart and there is nothing wrong with it. If a lot of people love each other, the world would be a better place to live.

An endlessly quotable text, a mysterious creator, and a community of similarly invested viewers – what could be bad about loving that?

Read more:

What makes some art so bad that it’s good?

The Room is back in select cinemas in Australia this week.

![]()

Renée Middlemost does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. ‘You can love something deep inside your heart and there is nothing wrong with it’: why we still love The Room, 20 years on – https://theconversation.com/you-can-love-something-deep-inside-your-heart-and-there-is-nothing-wrong-with-it-why-we-still-love-the-room-20-years-on-198665