Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Wendy Hargreaves, Senior Learning Advisor, University of Southern Queensland

David Neilson/ AAP

I have one prayer as I watch the Australian cricket team sing Advance Australia Fair patriotically before a match – “Please don’t turn on their microphone.” Like many Australians, their “joyful strains” of our anthem are … well, just strained.

It’s not their fault they misspent their youth playing cricket instead of taking singing lessons. And it’s not their fault they got so good they now have to sing in front of thousands before they can play.

But there is a fault. We’ve given them an anthem that average Aussies can’t sing in tune together.

Great unity?

According to former Prime Minister Scott Morrison, our anthem reflects “great unity”, but that wasn’t there at the start. It needed several “fixes”.

Peter Dodds McCormick’s 1878 composition began “Australia’s sons let us rejoice”. Daughters didn’t count. The National Australia Day Council later recommended substituting “Australians all”, which was adopted in 1984.

First Nations people were also omitted from McCormick’s original verses, ignoring their presence while glorifying British colonisation. More fixing from the Council swapped the offending verses for a politically neutral verse from McCormick’s Federation version with another tweak for gender-inclusive language.

Some Indigenous sport stars still refuse to sing the current anthem, as they say it doesn’t represent them.

Read more:

Our national anthem is non-inclusive: Indigenous Australians shouldn’t have to sing it

The remaining inappropriate lyric, “young”, was amended to “one” in 2021 by a governor-general’s proclamation. And as for “girt”? No, unfortunately, it remains, but it has united Australians in its own special way. We all think it’s odd.

Unfortunately, while focusing on unifying lyrics, we’ve missed a musical problem that’s divided voices since 1878. The note range of Advance Australia Fair is more than the average Australian will sing accurately. For inexperienced singers, which is most of us, our voices crack with the very disunity the government tried to fix.

What is note range?

The note range of a song is like the number of steps it takes to climb from the lowest to the highest point. If there are too many steps, the average Aussie would rather abandon the sweaty climb and hang out on the ground floor with a cold beer.

The range of Advance Australia Fair is 17 steps (called “semitones”). This is a bigger climb than other nations’ anthems, such as Britain’s 10 semitones in God Save the King, France’s 14 semitones in La Marseillaise and New Zealand’s 14 semitones in God Defend New Zealand. At least the Australian anthem is more modest than the Americans’ who, true to reputation, like doing everything bigger. The Star-Spangled Banner rises 19 semitones, resulting in some excruciating vocal cracks.

In theory, most average adult voices should be capable of climbing 17 steps and well beyond. We have the equipment. In practice, however, many inexperienced singers have problems with something called “registers”.

Why do registers matter?

Vocal registers are like gears in a car. We usually sing low steps in first gear, or “chest voice”. Chest voice is the most familiar and comfortable register because that’s the voice most people use when speaking everyday.

To sing higher, we subconsciously move small muscles in our throat to shift into second gear, or “head voice”.

Experienced vocalists spend considerable time developing strength in each register and making the gear change between them smooth and stable. Non-singers may not be not used to holding notes steady in second gear, and end up wobbling, yodelling and going out of tune.

Others won’t budge out of first gear, and change the melody instead. Whichever approach we take, it certainly isn’t “unified”.

Back to school

Schools are the unofficial training ground for anthems. Weekly assemblies make it the most regular practice session Aussies will ever experience. But those 17 steps don’t help.

Many beginner instrumentalists in school bands can’t play 17 notes in their first year of learning an instrument. Some players can’t do it by their second year either. And aspiring trumpeters? Unless they are the next James Morrison, hold your breath and cover your ears.

While there’s no rule that an anthem must be playable by children, it might increase our national pride if they could.

A simple solution

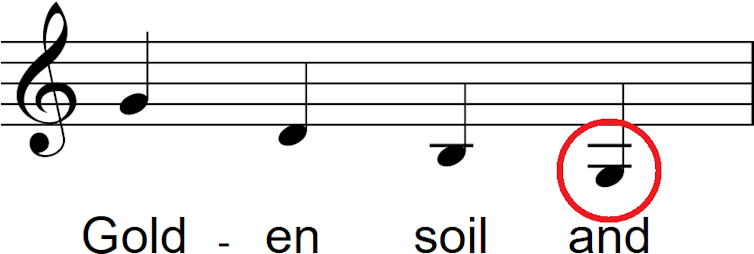

There is a remarkably simple solution to this musical problem dismembering our anthem – fix the note on the word “and”. Instead of this:

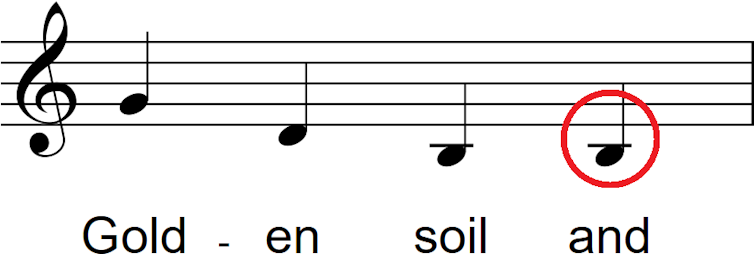

we can use a step already in the song, like this:

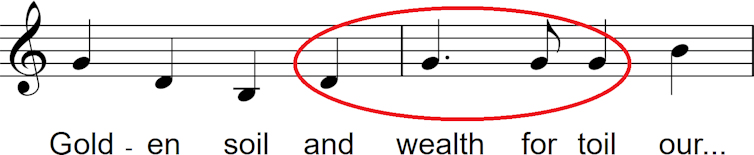

Alternatively, if that sounds odd, just substitute the steps from the first two bars like this:

Both options reduce the range to 14 steps which is singable in one register. If you start the song low, no gear change is required. Now we can sing the anthem and have a cold beer (or a lemonade for the kids).

If a proclamation can fix one word of our anthem for greater unity, then why not fix one note? Then, more everyday Australians could sing it together in unison. And isn’t that the point of an anthem?

![]()

Wendy Hargreaves does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. The Australian National Anthem has a big problem – the average Aussie can’t sing it in tune – https://theconversation.com/the-australian-national-anthem-has-a-big-problem-the-average-aussie-cant-sing-it-in-tune-197400