Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Jon Piccini, Lecturer in History, Australian Catholic University

One of the first moves of the newly elected Whitlam Labour government in December 1972 was to free seven men imprisoned for their beliefs. Their crime had been refusal to comply with the National Service Act, a so-called “lottery of death” that sent some 15,300 young Australians to fight in Vietnam. Two hundred of them never came home.

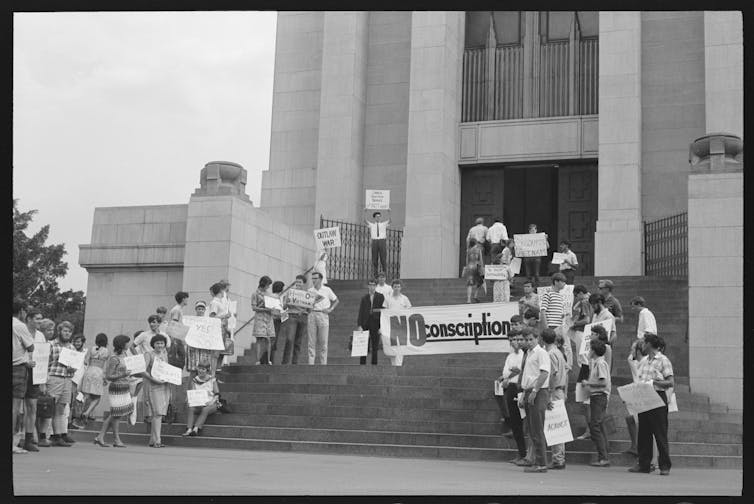

The issue of national service – often dubbed “the draft” following American vernacular – was perhaps the most powerful in the anti-war movement’s arsenal. “Draft resisters” mobilised public sentiment with their heroic stands, respectable mothers campaigned to “Save our Sons” and, as I explore in a newly published book chapter, the Australian wing of Amnesty International classed these men as “prisoners of conscience”.

Today, Australia grapples again with the question of criminalising conscience. Laws in several Australian states impose harsh penalties on the use of “direct action” by climate change activists. Fifty years ago, similar questions of a right to disobey sparked fierce debates: where should the legal limits of conscience lie?

Courtesy of the Search Foundation and State Library of New South Wales

In Australia, it is a crime not to kill

National service was re-introduced in Australia in 1964, with a previous scheme having quietly ended in 1959. The first “nashos” were committed to Vietnam in 1966. The scheme was highly selective – by its end some 800,000 20-year-olds had registered and less than 10% had been “called up”.

Opposition to national service emerged almost immediately, through such groups as the Youth Campaign Against Conscription. In November 1966, Sydney schoolteacher Bill White became the first person imprisoned for failure to comply with the act. He had applied for conscientious objector status almost a year earlier, but been denied because he did not fit the strict criteria.

Public outrage played a part in White’s early release in December 1966, but over time penalties became more harsh. John Zarb, a part-time postman, received a two-year sentence in October 1968 for refusing to comply with his call-up notice. His opposition to the Vietnam war only, rather than war in general, made him ineligible for objector status.

These moral-political stances encouraged further opposition. As well as releasing jailed objectors, Whitlam’s incoming government threw out cases against 350 individuals. For the anti-war movement, these cases demonstrated the conflict’s contradictions. As one activist leaflet put it: “In Australia, it is a crime not to kill.”

The politics of conscience

To a nascent human rights movement, however, the issue was not as clear-cut. Amnesty International, founded by the British lawyer Peter Benenson in 1961, established an early foothold in Australia. A Victorian section was founded in March 1962, and groups in other states soon followed.

One of the group’s appeals was its rejection of “Cold War” politics. By adopting “prisoners of consciences” from the first, second and third worlds, they could claim impartiality, while the use of letter writing as a tactic invoked the power of global opinion.

Yet the definition of a prisoner of conscience in the group’s early years proved controversial. To meet Amnesty’s definition, a prisoner needed to have been jailed for crimes of opinion and have not advocated violence. Infamously, this definition excluded Nelson Mandela. For Amnesty, the question of whether objectors like White or Zarb should be considered prisoners of conscience divided the Victorian and New South Wales sections.

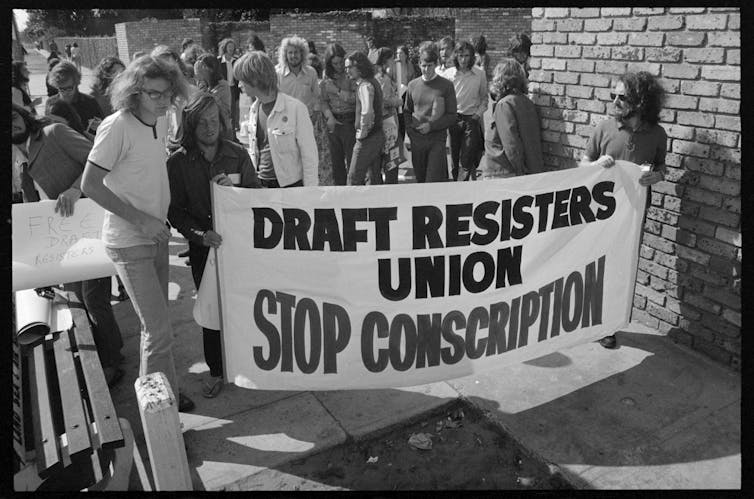

Courtesy of the Search Foundation and State Library of New South Wales

The Victorians believed those who “register for national service and apply for exemption”, but whose “applications fail either through some apparent miscarriage of justice or because the law does not presently encompass their objections […] are prima facie eligible for adoption”. However, those who “basically refuse to co-operate with the National Service Act” merely “maintain a right to disobey a law which they believe to be immoral” – and adopting them would “seriously damage […] our high repute”.

The New South Wales section condemned this “legalistic interpretation”. Instead, it insisted “the Non-Complier in gaol for conscientiously held […] views suffers no less than one who has tried in vain to act ‘according to the law’ ”. The Victorians’ belief that Amnesty should accept some degree of compulsion in democratic societies was also challenged: conscription was in fact a universal problem that occurred on both sides of the “Iron Curtain”.

Is it right to resist?

In the end, the views of the New South Wales section won out. Amnesty sections around the world adopted Australian non-compliers.

This clash of principles reminds us that human rights have never been straightforward. Rather, these ideas have long been open to contest and reinterpretation. From today’s vantage point, it also seems the Victorian section’s belief that the right to disobey could be limited was wildly optimistic.

Indeed, the sentencing of climate protester Deanna “Violet” Coco to 15 months in jail for the crime of disrupting traffic in New South Wales shows that the questions posed by Amnesty in the 1960s are very much still with us. The climate emergency is in many ways the Vietnam of today’s young people. The 50th anniversary of the release of resisters to that conflict should give today’s decision-makers pause for thought.

![]()

Jon Piccini does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Is there a ‘right to disobey’? From the Vietnam War to today’s climate protests – https://theconversation.com/is-there-a-right-to-disobey-from-the-vietnam-war-to-todays-climate-protests-193714