Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Michael Vardon, Associate Professor at the Fenner School, Australian National University

Image by Daniel Burkett from Pixabay , CC BY

Treasurer Jim Chalmers’ federal budget next week will for the first time include a section on wellbeing, which aims to measure how well Australians are doing in life.

The wellbeing budget will, among other things, assess the state of our natural places using a set of environmental indicators. But what indicators? And what environmental information should be used?

Getting meaningful environmental measures into the wellbeing budget won’t be easy. And tokenism won’t do.

We need a system providing comprehensive, regular and up-to-date information that can genuinely inform environmental and economic decisions.

Rob Blakers/AAP

An information ‘grab bag’

Australia has, for too long, relied on the five-yearly State of the Environment reports for updates on how our environment is faring, using a grab-bag of information. As the latest report noted:

Australia currently lacks a framework that delivers holistic environmental management to integrate our disconnected legislative and institutional national, state and territory systems, and break down existing barriers to stimulate new models and partnerships for innovative environmental management and financing.

In other words, we cannot get our environmental act together. Our responses to problems are often piecemeal and ineffective. We do not even have the information we need to fix them.

We’re yet to see what environmental information is included in next week’s wellbeing budget.

The Nine newspapers on Wednesday reported that no indicators have been agreed upon as yet, but the budget papers will contain a chapter on methods used in other jurisdictions, such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s long-running wellbeing framework.

Given the dearth of good information, the government must resist the temptation to rely on partial, uninformative or misleading environmental statistics.

These might include the number of listed threatened species (which would be larger if the environment department had been better-resourced) or the extent of the network of protected areas (which is large but significantly under-represents many ecosystems).

There’s no problem starting with what we have. But we must get to what we need.

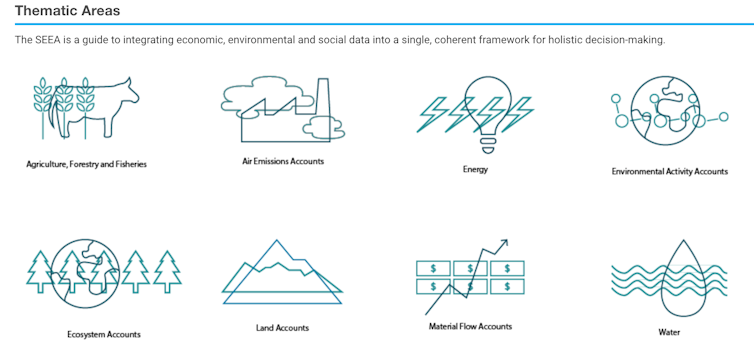

We could draw inspiration from the giant information and policy apparatus in the public service that helps us track economic progress, and use a United Nations framework called the System of Environmental Economic Accounting (sometimes shortened to SEEA).

Image by Wallula from Pixabay, CC BY

The giant information and policy apparatus

Every day, thousands of public servants work to gauge what the economy is doing and figure out what it means for industry, the government and the public.

Gross domestic product is measured, reported and debated. The Australian Bureau of Statistics releases it to a set schedule, without needing ministerial approval. Good or bad, the data comes out.

Officials from treasury, the finance department and the Reserve Bank pore over the figures. Their analyses and advice are sent to the treasurer, prime minister and cabinet.

If growth is too strong, the Reserve Bank might increase interest rates. If the economy is weak, the government might stimulate it with infrastructure spending.

Compare this to what we have for the environment.

A five-yearly State of the Environment report. In between reports, environmental problems are identified by scientists, environment groups and concerned citizens. Environmental laws are largely reactive. The agencies tasked with responding have limited funding and information.

The result? We consume the environment salami, one slice at a time, without knowing how much is left.

One example is the box-gum grassy woodlands once common across much of southeast Australia. These woodlands were protected under Australia’s most significant environmental law, the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act.

A recovery plan was prepared. But there’s no evidence the plan was delivered and the ecosystem is still no better off.

In his 2020 review of the EPBC Act, Professor Graeme Samuel recommended an overhaul, saying

National Environmental Standards should be immediately developed and implemented to provide clear rules and improved decision-making.

Recognising this couldn’t happen without a system of comprehensive environmental information, Samuel recommended building one including national environmental-economic accounts.

These should be tabled annually in parliament alongside traditional budget reporting.

Samuel’s approach strongly resembles the way governments manage the economy: use regular information to adjust policy settings to stay on trajectory towards desired outcomes.

Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek has hinted she is inclined to follow Samuel, describing his review as “thorough”.

So if environmental management is going to emulate economic management and be informed by the accounts Samuel envisioned, then just what are they?

What is environmental-economic accounting and what’s the UN-backed system?

Environmental-economic accounting is an information system blueprint.

SEEA-based accounts are ready-made to provide information for environmental decision-making, just as the national accounts inform economic decision-making.

UN

This UN-backed system was only completed in 2021, so real-world examples remain few. But one Victorian study shows the potential.

The accounts in the study showed the economic benefit of harvesting Central Highlands native forests for timber were far outweighed by the economic benefit of maintaining the forests for carbon storage and water supply. In other words, the forest is more valuable if you just leave it alone.

Ceasing harvesting would also bring major biodiversity gains. An assessment of all regional forest agreement areas in Victoria gave similar results.

On paper, Australia’s governments in 2018 endorsed the SEEA and adopted a national strategy to implement it.

In practice however, these governments are yet to produce the vision or political will to build a such a system that will actually inform environmental decisions.

Overseas, change is underway. The US, previously a laggard, now has an ambitious strategy to build environmental-economic accounts into their national information system.

An urgent need

Establishing a comprehensive set of environmental-economic accounts is the first step in delivering integrated environmental and economic management.

The United Nation’s System of Environmental-Economic Accounting offers a way forward. Graeme Samuel recommended it. Now government must deliver it. But it will take time and it won’t be cheap.

Early signs are positive but can Plibersek and Chalmers stay the course? Our future depends on it.

Read more:

You probably missed the latest national environmental-economic accounts – but why?

![]()

Michael Vardon receives funding from a variety of organisations for the development and application of environmental-economic accounting.

Peter Burnett does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Our environmental responses are often piecemeal and ineffective. Next week’s wellbeing budget is a chance to act – https://theconversation.com/our-environmental-responses-are-often-piecemeal-and-ineffective-next-weeks-wellbeing-budget-is-a-chance-to-act-188366