Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Stephen Bartos, Professor of Economics, University of Canberra

Wouldn’t you know it? Last Thursday the Parliamentary Budget Office released more than 1,000 pages of costings, for promises in the election we just had.

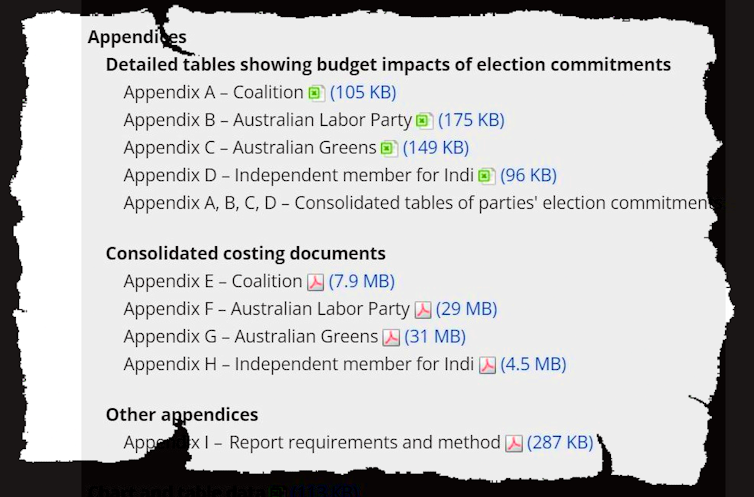

They came in 16 parts, each separately downloadable, along with a video message, charts and tables, explanations, and summaries.

It was a lot of work, but it was too late to have an impact. We’d already voted.

The report was covered briefly by the Canberra Times, a couple of regional papers, and online site Crikey. It garnered close to zero attention.

In its wake, the shadow treasurer Angus Taylor issued a media release attacking Labor for increasing the projected budget deficit.But that too was old news. During the campaign, Labor had said that’s what it would do.

The ratio of attention paid to the number of pages produced was dismal.

The letter of the law

This isn’t the fault of the Parliamentary Budget Office. It is required by law to release the report 30 days after the election. It doesn’t have the power to compel the parties to submit lists of their policies for analysis until 5pm on election eve.

Getting even that power was a close-run thing. Treasurer Wayne Swan added the requirement to the legislation in a 2013 amendment.

Trouble is, it is hard to discern from the public record why he did it. The explanatory memorandum and speeches assert it will be good for transparency and accountability but do not explain how.

Definitionally, to the extent there is more detailed information, there is greater transparency. But if the information is delivered after people have voted, it’s worth asking how it could improve accountability.

Data should be useful

It can’t be taken for granted that more data equals more accountability. Data needs to be used for something – to spark debate, or inform votes.

NSW had a Parliamentary Budget Office before the Commonwealth, which means the amendment might have been based on a NSW requirement for major parties to give the NSW office a list of their policies.

But the difference is that in NSW the report is published five days before the election. There’s a chance it can swing votes.

Read more:

Elections used to be about costings. Here’s what changed

Publishing it after the election, as the Commonwealth office does, means it is almost guaranteed to be ignored.

Does anyone really care what the costs were for the party that lost? Or those for the Greens or even the Member for Indi, who wasn’t required to take part but in 2022 did so voluntarily?

The information about the party that won might be useful, but it will soon be overtaken by the October budget which will provide updated costings.

Not that there is anything wrong with the PBO report. It is comprehensive, detailed, and has excellent methodology.

It goes beyond the numbers provided by the parties and includes discussion of measures that affect the government’s balance sheet but not the budget balance. But it’s at the wrong time.

It is far from the only long and complicated report with almost no impact. And if all that mattered was the direct cost of producing it, it wouldn’t much matter.

But there’s an opportunity cost: the other things the PBO staff weren’t doing while they were working long hours producing those 1,000-plus belated pages.

Before the election would be useful

The PBO produces research reports, budget explainers, chart packs and many other highly useful information pieces. Particularly notable was a timely and relevant series of publications on the budget impact of COVID-19.

Somewhere in Parliament House there’s an empty bookshelf full of unwritten reports that weren’t produced because of the time the PBO spent on reports like this one.

If the PBO published a report on promises before the election – accepting likely gaps due to time pressures or late promises – it could actually inform voters.

Read more:

Costing the promises: what is a Parliamentary Budget Office?

There is however a major barrier in the legislation. Whereas in normal times the PBO has to deal confidentially with costings requests, if a request is submitted during a campaign, the PBO is required to make policy and its costing public.

No sensible party is going to take the risk of submitting a policy, having it made public, and then finding out it is unaffordable.

The only policies anyone submits to the PBO in the caretaker period after an election is called are

-

those from minor parties – they don’t mind if their policies get negative publicity for being expensive, they are grateful if anyone notices them at all

-

policies where the costs are predictable or known

Changing this, and requiring the PBO to release summaries of the budget impact of promises (say) five days before the vote (as happens in NSW) would make the effort it puts in worthwhile.

Stephen Bartos was NSW Parliamentary Budget Officer for the 2015 and 2019 elections.

![]()

Stephen Bartos was NSW Parliamentary Budget Officer for the 2015 and 2019 elections. He has written for Crikey and The Mandarin.

– ref. Election promises should be costed before polling day, otherwise it’s too late – https://theconversation.com/election-promises-should-be-costed-before-polling-day-otherwise-its-too-late-187149