Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Rebecca J. Collie, Scientia Associate Professor of Educational Psychology, UNSW Sydney

Shutterstock

Stress is common among teachers, and recent reports suggest it’s getting worse. We need to understand the sources of this stress to improve support for teachers. Growing teacher shortages in Australia underscore the need for this support.

It is also important to identify whether there are patterns of stress experienced by individuals and groups of teachers within a school. This knowledge will tell us whether support for teachers should be targeted individually or to a teaching staff more broadly.

Read more:

Almost 60% of teachers say they want out. What is Labor going to do for an exhausted school sector?

Our study involving 3,117 teachers at 225 Australian schools shows sources of stress do vary among individual teachers. At the same time, the school environment – workloads, student behaviour and expectations of teachers – appears important. At some schools the stress experiences of individuals mirror those of the teaching staff more broadly.

So managing stress is not just the responsibility of individual teachers. Schools have an important role to play in developing a workplace that helps to minimise their teachers’ stress.

What are the sources of teachers’ stress?

In our study, published in Teaching and Teacher Education, we examined three common sources of stress at work to see how these affect well-being among individual teachers and across a whole school teaching staff.

These three sources of stress are:

-

workload stress – teachers’ sense they have too much lesson preparation, instruction or marking work in the time available to them

-

student behaviour stress – teachers’ sense that student behaviour is overly disruptive or aggressive

-

expectation stress – teachers’ sense that professional/registration bodies and parents are placing very high or unrealistic expectations on them.

We first examined how the three sources of stress co-occur among teachers to identify teacher stress profiles. That is, we wanted to see if there are distinct types of teachers who experience similar patterns across the three sources. For example, are there teachers with low or high levels of all three sources of stress, and are there teachers who have mixed levels of the sources of stress?

Next, we wanted to ascertain whether different types of schools are identifiable as being more or less stressful based on the make-up of their teacher stress profiles. That is, we set out to identify different school profiles.

Once we had identified teacher and school profiles, we examined whether the different profiles were linked with work strain and work commitment. Work strain refers to the adverse outcomes of stressful work – such as feeling highly stressed and reduced mental or physical health. Work commitment refers to teachers’ attachment to their profession.

Ideally, teachers experience low strain at work, but high commitment.

Read more:

Teachers can’t keep pretending everything is OK – toxic positivity will only make them sick

What teacher profiles did we find?

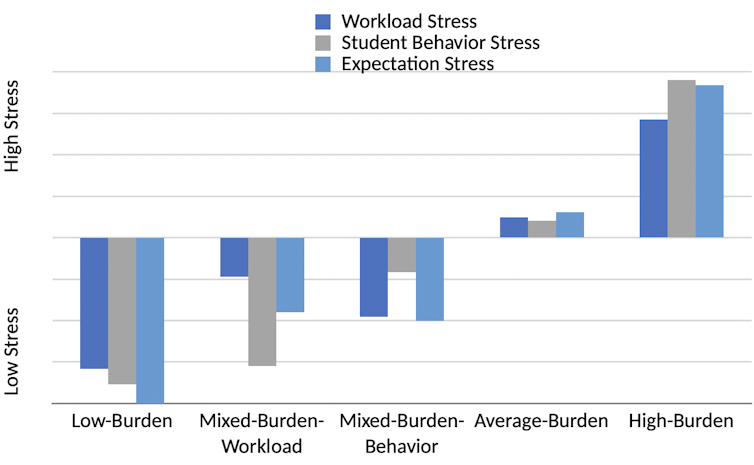

Our analysis used data from the OECD Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) 2018. We identified five teacher profiles:

-

low-burden profile (7% of teachers in our sample) displaying very low levels of all three stressors

-

mixed-burden-workload profile (15%) displaying below-average workload stress, very low student behaviour stress and low expectation stress

-

mixed-burden-behaviour profile (19%) displaying low workload stress, below-average student behaviour stress and low expectation stress

-

average-burden profile (41%) displaying slightly above-average levels of all three stressors

-

high-burden profile (18%) displaying high workload stress and very high student behaviour and expectation stress.

Collie & Mansfield 2022, Author provided

Looking at links between profiles and outcomes, the low-burden profile and the two mixed-burden profiles generally displayed the lowest work strain and highest work commitment.

Read more:

Higher salaries might attract teachers but pay isn’t one of the top 10 reasons for leaving

What school profiles did we find?

We then examined how these teacher profiles are distributed in schools. We identified three school profiles:

-

workload-oriented-climate profile (17% of schools in our sample) composed mostly of teacher profiles with high workload stress, but also a sizeable proportion displaying lower stress

-

behaviour-oriented-climate profile (23%) composed mostly of teacher profiles with high student behaviour stress, but also a sizeable proportion displaying lower stress

-

higher-pressure-climate profile (60%) composed mostly of teacher profiles with above-average to high levels of all three sources of stress.

Teachers who collectively displayed the highest levels of work strain tended to work in higher-pressure-climate schools. Levels of work commitment were also lowest among teachers in those schools.

Read more:

COVID and schools: Australia is about to feel the full brunt of its teacher shortage

What does this mean for teachers and schools?

One notable finding was the differentiation between workload stress and student behaviour stress in two teacher profiles and two school profiles. Some teachers and schools were higher in student behaviour stress. Others were higher in workload stress. And other profiles had similar levels of all types of stress.

These results suggest sources of stress at work are not necessarily specific to the individual, but reflect a broader school climate as well. So, teachers’ stress isn’t just an individual issue – some schools are more stressful places to work.

In practice, it is important that teachers have their own strategies to manage stress. At the same time, our findings suggest schools and educational systems should be aware of teachers’ collective experiences of stress and provide school-wide supports.

To reduce workload stress, research suggests supportive mentors are helpful. It’s also helpful to develop professional learning communities to share the loads of lesson preparation and marking moderation.

Reducing workload across the school is also critical. Decreasing teachers’ face-to-face teaching time and administrative tasks have been suggested as ways to do this.

Providing professional learning opportunities to develop teachers’ classroom management skills might help reduce student behaviour stress.

A positive learning climate at school is also important. When students feel supported and are more engaged in their learning, they are less likely to be disruptive. In particular, research suggests it is important that all students feel cared for, have opportunities to succeed in their learning, and are given a say in content and tasks in the classroom.

Finally, research suggests school leaders can help reduce expectation stress by seeking out teachers’ perspectives and conveying their trust in them as professionals. Likewise, positive school-home partnerships can help ensure teachers, school leaders, students and parents are aligned in their goals.

![]()

Rebecca J Collie receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Caroline F. Mansfield does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Teachers’ stress isn’t just an individual thing – it’s about their schools too – https://theconversation.com/teachers-stress-isnt-just-an-individual-thing-its-about-their-schools-too-183451