Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Katie Lee, PhD Candidate, The University of Queensland

Shutterstock

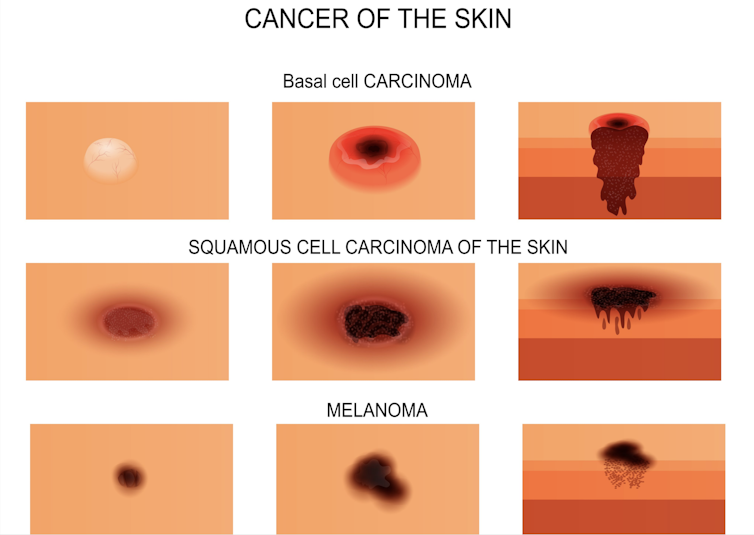

Two in three Australians will have a skin cancer in their lifetime, nearly all of them basal cell carcinomas (BCC), squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) or melanomas.

If the spot removed was more like a sore or lump than a mole, it’s likely your doctor is talking about basal or squamous cell carcinoma, also called keratinocyte cancer or non-melanoma skin cancer. (See our piece on melanomas, which look more like moles, here).

Read more:

The doctor says my mole is a melanoma. What happens next?

About 80% of all cancers treated in Australia are skin cancers – most of which are BCCs or SCCs. But because BCCs and SCCs are not notifiable diseases, there is no official tracking system for them.

It’s difficult to know how many are diagnosed each year, but based on Medicare data, there are more than 900,000 treatments for BCC and SCC each year – some of these will be separate treatments of the same cancer.

Although they are less likely to be fatal than melanoma (around 560 deaths per year in Australia) the sheer number of them costs more than A$700 million a year to diagnose and treat.

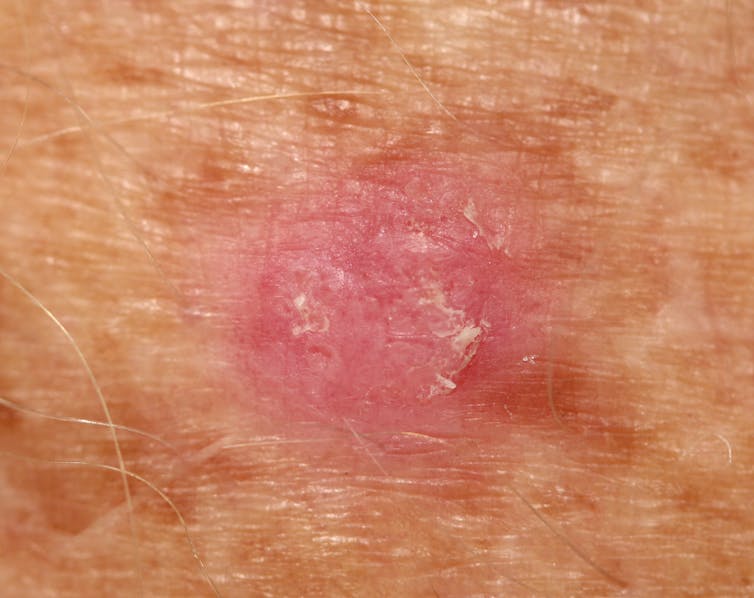

When diagnosed early, BCCs and SCCs are usually straightforward to treat. But don’t be complacent. Left untreated, they will grow wider and deeper, as much as 20cm across. They will invade and destroy surrounding tissue, even bone.

Shutterstock

What’s the treatment?

The treatment path for SCCs and BCCs is much less clear-cut than for melanomas. There are few firm guidelines and many treatment options, but here are the most common tactics.

Excision is the first-line treatment because it is the most likely to be curative and prevent recurrence, and the tumour can be sent to a pathologist for microscopic examination.

The pathology report will indicate if there are any signs of an unusually aggressive variant of the tumour, and if the whole tumour and a safety margin of surrounding healthy skin has been removed. If not, your doctor will remove a bit more to ensure the whole tumour is gone. The safety margin size depends on the size, type and location of the tumour, and can range from 2mm to 1cm.

Shutterstock

Many BCCs and SCCs require only a simple excision to cure. However, those on delicate parts of the face with many nerves and small muscles, or close to bones and cartilage, are difficult to safely cut out. If they have grown down into underlying fat, muscle or bone, surgery might not be appropriate.

The right treatment in this case depends on the size and location of the tumour, whether it has well-defined or blurry edges, is scar-like or gelatinous. Informed patient preference is also important. Your doctor may freeze the tumour off, cut it out with a sharp scoop and cauterise the wound, or prescribe a cream that encourages a strong immune reaction or reacts with light to damage the cancer cells.

Your doctor may also refer you to a specialist for radiotherapy, which involves a very targeted dose of radiation, generally x-rays, to kill the tumour by damaging its DNA, and is performed by a specialist radiation oncologist.

Read more:

Health Check: do I need a skin cancer check?

Can it spread?

If the pathology report shows the cancer has invaded a nearby nerve, or if you have painful, tingling or crawling symptoms indicating a nerve is compromised, more aggressive excision or radiotherapy might be suggested. In the case of SCC, you may also be offered an MRI scan to see how far it has spread.

In this case you will be referred to a radiation oncologist to discuss whether radiotherapy would be helpful. Radiotherapy may also be considered if a BCC has invaded underlying bone, or if there is evidence of BCC cells in the nearby lymph nodes.

It’s extremely rare for BCC to spread away from the original site: only about 0.1% spread into the rest of the body. However, if it is very thick, has returned multiple times, or has other aggressive features, your doctor may also refer you to a specialist to examine your lymph nodes.

Shutterstock

SCCs are somewhat more likely to spread, but due to the lack of compulsory reporting it’s difficult to tell the actual rate. Some studies report about 4% of SCCs spread to the lymph nodes, but these are often drawn from higher-risk cases, so the true rate is likely to be lower.

Your doctor may refer you for lymph node examination if your SCC was more than 2cm wide, or has spread into the fatty tissue just below the skin. SCCs on the head and neck, those with poorly defined edges, tender, inflamed lesions and lesions sitting at the edge of the lips may also require more attention.

Read more:

Why does Australia have so much skin cancer? (Hint: it’s not because of an ozone hole)

What follow-up is needed?

Your GP or dermatologist will want to see you for regular full-body skin checks after your initial treatment. This is because 44% of people with a basal cell carcinoma and 18% with a squamous cell carcinoma will have another one.

How often the checks are recommended depends on the original location, pathology report and treatment choice, but is usually once a year. You will also be taught what to look out for so you can bring any suspicious skin spots to your doctor early.

People with strongly suppressed immune systems, such as organ transplant recipients, need to take special care to have regular checks for skin cancers as their immune systems will not be doing their regular job of finding and destroying all sorts of cancers at an early stage. Regular checks can reduce skin cancer-related ill-health and deaths by as much as a third in organ transplant recipients.

Read more:

Common lumps and bumps on and under the skin: what are they?

In areas of skin that have significant UV damage and signs of early superficial skin cancers, your doctor may suggest a “field treatment” to remove the damaged skin cells. The most common is a cream used for four weeks, but other options include laser treatment.

It’s never too late to reduce your risk of further keratinocyte cancers. Recent research has shown taking up sun-smart behaviour – slip, slop, slap, seek and slide – even late in life, significantly slows down the rate of new skin cancers and in some cases even seems to allow the body to heal some precursor lesions.

![]()

Katie Lee receives funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council.

H. Peter Soyer is a shareholder of MoleMap NZ Limited and e-derm consult GmbH, and undertakes regular teledermatological reporting for both companies. He is a Medical Consultant for Canfield Scientific Inc, MoleMap Australia Pty Ltd, Blaze Bioscience Inc, and a Medical Advisor for First Derm. He holds an NHMRC MRFF Next Generation Clinical Researchers Program Practitioner Fellowship (APP1137127) and several other NHMRC and MRFF grants. He is a Board Member of Melanoma and Skin Cancer Trials Limited and the Queensland Skin and Cancer Foundation. He is employed by The University of Queensland and works as Visiting Medical Officer at Metro South HHS.

Erin McMeniman does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. The doctor says I have skin cancer. What happens next? – https://theconversation.com/the-doctor-says-i-have-skin-cancer-what-happens-next-182414