Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Frank Bongiorno, Professor of History, ANU College of Arts and Social Sciences, Australian National University

The first two weeks of the 2022 election campaign have increased the possibility that neither of the two major parties will gain a majority in the House of Representatives.

While the prospect may make some people queasy, the country’s political history tells us hung parliaments can work effectively and support productive, and even strong, governments.

Indeed, it is possible an indecisive election in 2022 might produce a better government than one that results in a narrow majority in the House of Representatives for one side or the other.

On the Coalition side, especially, there are differences of outlook between the partners as well as within each party that might produce the same kinds of unpredictability the naysayers often attribute to minority government.

There have been several stable minority state and territory governments over the past 30 years. But at the federal level, since the two-party system emerged in 1910, there are really two precedents for a hung parliament and minority governments.

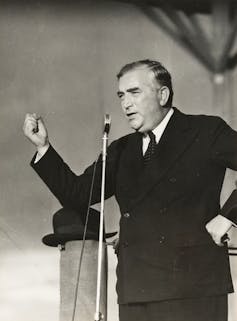

The first was between 1940 and 1943, during the second world war. Robert Menzies and Arthur Fadden each led non-Labor minority governments, and these were succeeded by John Curtin’s Labor government.

The second precedent was between 2010 and 2013, when Julia Gillard, followed briefly by Kevin Rudd, led a minority government supported by the Greens and some of the crossbench.

AAP/Alan Porritt

Minority government in war-time

The 1940 election left the Australian Labor Party with voting support equal to that of the United Australia Party (UAP, a predecessor to the Liberal Party) and the Country Party (predecessor to today’s Nationals) together. Two independents, representing traditionally conservative seats, held the balance. One of those independents, businessman Arthur Coles, soon joined the UAP, but withdrew after it changed leaders.

Coles was elected in 1940 to the seat of Henty, which included the south-eastern suburbs of Melbourne, some of which now form part of the seat of Goldstein contested this year by another independent, Zoe Daniel.

The other independent seat in 1940 was held by wheat farmer Alexander Wilson, who had wrested the seat of Wimmera in Victoria’s north-west from the Country Party in 1937. In contrast with Coles, he leaned left – toward Labor – rather than right.

Museum of Australian Democracy

In a divided House of Representatives in 1940 and 1941, Menzies more than once invited Curtin to form an all-party or “national” government. Curtin, fearing a split in the Labor Party, declined the invitation and Menzies led a United Australia-Country Party coalition government supported by the independents.

But, while rejecting a national government, Curtin suggested something else that would help minority governments manage the House of Representatives during wartime: he accepted Labor’s membership of an Advisory War Council (AWC). It drew all the major parties in the parliament into the process of making decisions on Australia’s war effort. The two independents eventually switched sides, but not before giving the Coalition government ample opportunity to succeed. The instability of that government had nothing to do with the independents. Its problems were self-inflicted, coming from within.

When Curtin succeeded Menzies and Fadden as leader of a minority government, he kept the AWC. Between 1941 and 1943, one observer noted,

not a piece of legislation could be framed by the [Labor] Cabinet with the certainty that it would be passed in the form in which the Government framed it.

But with the support of the independents and deft use of the AWC, Curtin was able not only to lead a stable government but to implement ground-breaking legislation. These included the Uniform Tax legislation that led to the Federal Parliament monopolising income taxation ever since.

chifley.org.au

The Gillard-Greens alliance

If this seems like ancient history, we have a more recent exemplar that minority government can be made to work. Between 2010 and 2013, Julia Gillard was able to secure workable and reliable parliamentary majorities in both houses of parliament, despite Labor’s lack of control of either house.

In some areas, she was able to succeed where Kevin Rudd, who had a comfortable majority in the house but no majority in the Senate, had failed. Some 561 pieces of legislation were passed, many more than during the Rudd government and, remarkably, more than when John Howard had control of both houses (2005-2007).

Like the difficulties of the Menzies government in 1940-41, the Gillard government’s major problems did not arise so much from lack of parliamentary numbers as from internal divisions arising from the rivalry between Gillard and Rudd.

Read more:

Farewell to 2021 in federal politics, the year of living in disappointment

Could 2022 be next?

A minority government established in 2022 could consider similar mechanisms to the Advisory War Council: a variation on the existing National Cabinet, consisting not only of the leaders of Commonwealth and state governments, but of representatives of the opposition, minor parties and independents as well. Its remit could be extended beyond COVID-19 to encompass necessary reforms given a mandate by the people, such as a national integrity commission, and climate change and energy policy.

Curtin was helped, too, by the United Australia Party Speaker of the House of Representatives, Walter Nairn, remaining in his post for most of the parliamentary term, giving him a more stable majority in the house. Had Tony Smith remained in parliament, a minority Albanese government might well have welcomed him continuing to perform this role. There would be nothing to stop one of the crossbench, moreover, accepting the role to become an “independent speaker”.

What does history tell us might happen if a divided House of Representatives is the outcome in May?

AAP/Alan Porritt

Most of the crossbench will have won their seats campaigning for a robust national integrity commission, stronger action on climate change and water policy, and more serious action on gender equity. Labor’s policies on these matters place it in a stronger position to negotiate with the independents. But some of the independents, most of whom represent “natural” Coalition seats, might fear the electoral consequences of supporting a Labor minority government.

The experience of independents Tony Windsor and Rob Oakeshott is instructive here. They showed they could win historically National Party seats. But their experience would be a warning to an independent in a “natural” Coalition seat about the dangers of supporting Labor. While neither recontested his seat in 2013, there was sufficient evidence of a local backlash to indicate that holding on, in the context of a national swing to the Coalition, would not have been easy. As we pointed out in an earlier article, another scenario after May 21 might be the independents supporting a minority Coalition government supported by someone other than the present prime minister.

Whatever the case, it is entirely possible a hung parliament might provide the circuit-breaker for a parliament that needs to grapple with much needed national reforms.

Australians have many things to fear about the future, but a minority government is among the least of their problems. If it should happen, it would rather reflect the loosening hold of the major parties on the votes of Australians, and so would be an authentic expression of an important turn in the history of our democracy.

![]()

Frank Bongiorno is a member of Kim For Canberra (Senate election) and has donated to Climate 200.

David Lee is a member of the Australian Labor Party and has donated to Climate 200.

– ref. Could the 2022 election result in a hung parliament? History shows Australians have nothing to fear from it – https://theconversation.com/could-the-2022-election-result-in-a-hung-parliament-history-shows-australians-have-nothing-to-fear-from-it-181484