Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Erica Russ, Senior Lecturer, Southern Cross University

Shutterstock

The crisis in child welfare in Australia has, for too long, resulted in too many children taken into care, with many not receiving the timely assistance and care they and their families need.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are 11 times more likely to be taken into care. Children from culturally diverse families, and children and parents with disability are also over-represented in the system. Children often enter child protection systems for many reasons, including neglect because of poverty. Families need support to care for their children safely, rather than having their children removed.

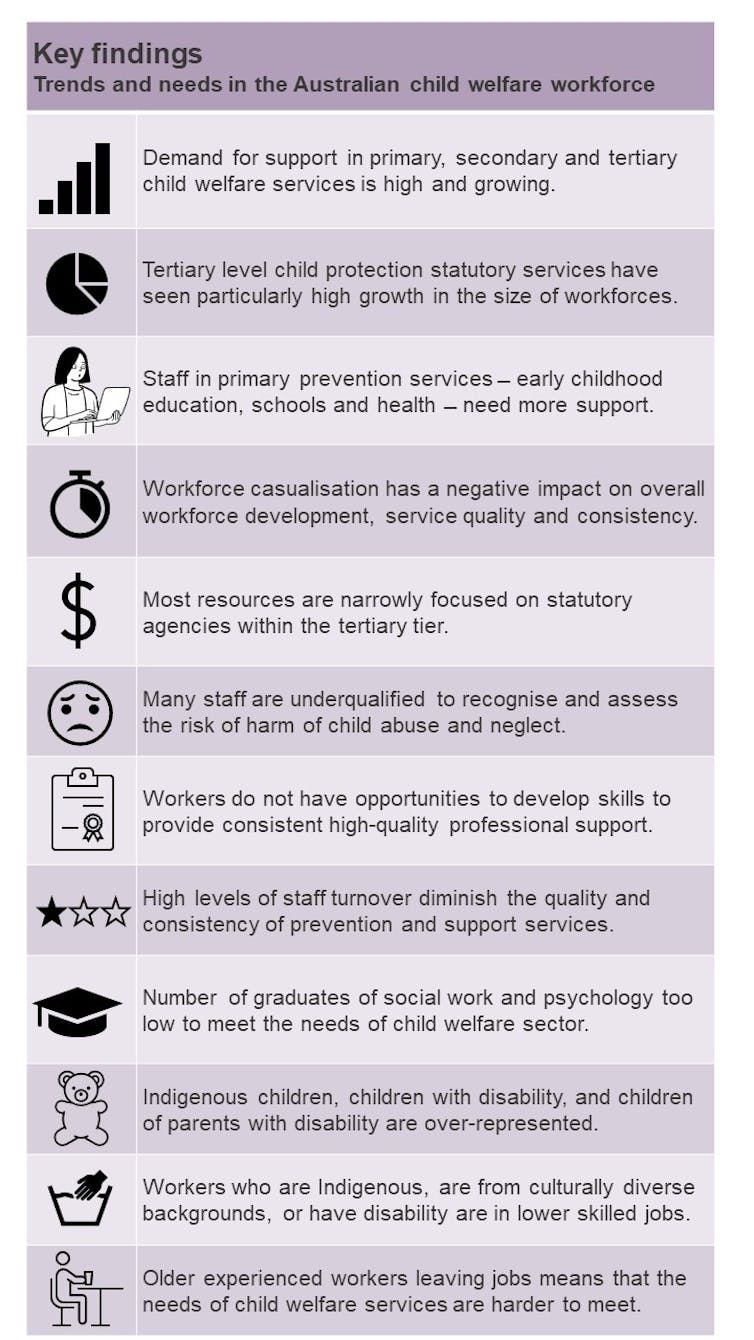

Our national study, published by the Institute of Child Protection Studies, found this problem is made worse by poor workforce planning. The need for child welfare services has gone up but the current workforce is ill-equipped and unable to respond.

Reform is urgently needed to reshape the system and its workforce towards more services that prevent problems emerging in the first place, rather than a system geared towards removal. Such reform would support children to remain safely with their families.

Read more:

The faulty child welfare system is the real issue behind our youth justice crisis

A prevention approach

Our study examined broad-ranging, publicly available data to investigate emerging trends, issues and needs in the child welfare workforce and the educational profile of the workforce.

We approached this research from a public health perspective, where the priority is prevention and early intervention.

We wanted to evaluate how ready this workforce is to implement principles outlined in the National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children 2009-2020, a guiding policy document agreed upon by state and federal governments at the 2009 Council of Australian Governments (COAG) meeting.

These principles envision a system where services and key stakeholders – such as teachers, health workers and community service workers – are funded to work together with children and families to reduce vulnerability and prevent child abuse and neglect.

Research has also identified ways we can invest in supporting parents to address early issues that might otherwise become a child protection concern.

Shutterstock

If early intervention approaches prove to be not enough, more intensive services exist to support more vulnerable families to reduce the risk of child abuse and neglect. Then, the formal state child protection response (sometimes known as the “tertiary tier” of the broader child welfare system) should only kick in if the supportive services are not able to manage or reduce the risk of child maltreatment.

Even when someone notifies a state child protection authority about a child’s safety, they and their family don’t always get the help they need. Safety concerns keep on being raised. Removal of children may be necessary in some instances. But removal often does not ensure the safety and well-being of children.

We need early, specialist support that is actually helpful for children and families, culturally appropriate, and meaningful. This is by far the most effective way to deal with child abuse and neglect and promote child safety and well-being, while minimising removals.

To achieve this goal, workforce reform is needed.

A question of resourcing

The workforce for the preventative and supportive services in the child protection system is poorly defined and resourced.

Many of these workers – teachers, early childhood educators, nurses, GPs – do not have the qualifications or skills needed to recognise and assess risk of harm and provide needed support.

These problems inherent with prevention and support increases the pressure on the child protection systems.

Most of the funding and resources are aimed towards the more severe end of the child protection systems, yet high levels of staff turnover continue, which negatively affect the quality and consistency of service.

Trends and needs in the Australian child welfare workforce: An exploratory study

Diversifying the workforce

Our analysis highlighted that workers in child protection systems are overloaded yet still must deal with complex situations. They often lack the training or skills and have limited experience to draw on.

The number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workers, culturally diverse workers, and workers with disability does not align with the disproportionate representation of these groups within child protection systems.

Those that are in the child protection system tend not to be in leadership roles, and less likely to be making decisions.

Educational programs key to child welfare – such as social work, psychology and human services – are not meeting the increased demand for workers.

What would make a difference?

Investment priorities must shift. Funding needs to be aimed at preventative and supportive services for vulnerable children and their families, rather than at the part of the system that deals with removals. We must respond to people’s needs early and decrease the pressure on child protection systems.

The preventative child welfare workforce (including teachers, early childhood educators, nurses, GPs and other community service workers) needs to be better resourced and supported. These stakeholders must be able to develop the skills and knowledge necessary to identify and respond to the risk factors.

Better professional development for all workers in the child welfare sector is urgently needed.

The numbers of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workers, in support and child protection services needs to be increased in a way that recognises their knowledge, expertise and value in keeping children safe. More government funding and support for First-Nations led organisations like SNAICC (Secretariat of National Aboriginal and Islander Child Care) could potentially assist with this.

There is also a need for more culturally diverse workers and those with a disability.

Higher education providers and child welfare sectors must work together to plan for the continuing demand and future needs in child welfare services.

![]()

Erica Russ has prior experience working in child protection and have previously undertaken other state government funded research related to child protection. She is a member of the Australian Association of Social Workers. This story is part of The Conversation’s Breaking the Cycle series, which is about escaping cycles of disadvantage. It is supported by a philanthropic grant from the Paul Ramsay Foundation. The researchers would like to acknowledge seed funding for this project provided by the University of New England, Faculty of Medicine and Health and New England Institute of Healthcare Research Collaborative Research Scheme.

Bob Lonne is am a member of the Australian Association of Social Workers.

Daryl Higgins receives funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council, a range of Australian, state, and territory governments, and non-government agencies. He is a member of the Australian Psychological Society.

Louise Morley has previous experience working in the child protection field and has previously undertaken other state government funded research related to child protection. She is a member of the Australian Association of Social Workers.

Maria Harries and Mark Driver do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. The workforce in the child protection system needs urgent reform – https://theconversation.com/the-workforce-in-the-child-protection-system-needs-urgent-reform-180950