Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Leon Salter, Postdoctoral Fellow, Massey University

GettyImages

Largely overlooked in the recent easing of COVID restrictions has been the unequal impact on marginalised groups such as gig workers.

While for much of the past two years there was a sense of collective risk mitigation by the “team of five million”, the government has since shifted that burden more towards individuals and personal responsibility.

But this avoids the fact that not all individuals have to negotiate the same amount of risk. And research shows gig work is one of the riskiest types of employment during a pandemic.

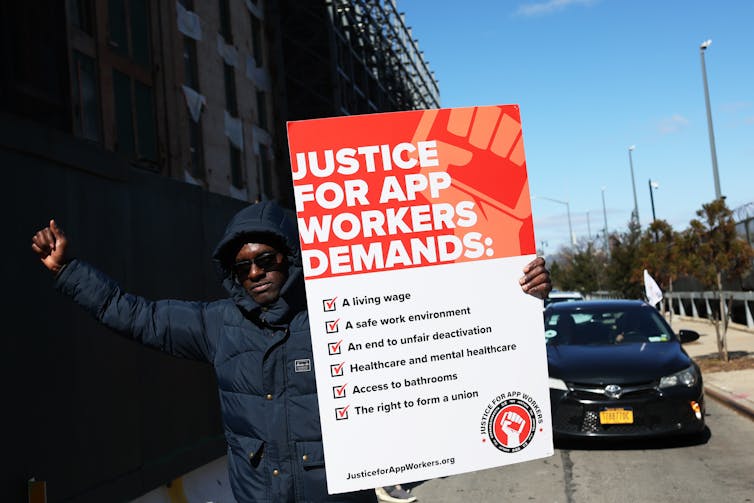

Furthermore, gig workers lack a public voice with which to communicate these risks to the general public and decision makers. But as our recent report – Experiences with COVID-19 Among Gig Workers – shows, these workers have been at a high risk of both contracting and transmitting the COVID-19 virus.

No way to speak out

We interviewed 25 rideshare and delivery drivers about their experiences during the pandemic. We found the structural features of their employment not only exposed them to increased risk from the virus, but also offered minimal protection should they be too ill to work.

While conventional businesses have established infrastructures for voicing dissatisfaction with COVID policy – through organisations such as Hospitality NZ, for example – gig workers lack equivalent communication channels.

Read more:

Gig workers aren’t self-employed – they’re modern-day feudal serfs

This inequality also extends to gig workers’ access to culturally appropriate preventive health information. Not unlike the inequities faced by Māori and migrant communities, this leaves gig workers (many of whom are also migrants who don’t speak English as their first language) more vulnerable to the negative health effects of COVID-19.

Such risk is compounded by the structural features of gig work. Our report is grounded in the voices of workers themselves and argues that seven structural features influence their experiences: the work is piecemeal, precarious, individualised, gamified, dehumanised, automated and hyper-competitive.

GettyImages

Algorithm as manager

By its nature, the work is driven by immediate supply and demand – drivers are paid for each micro-transaction, rather than a wage, meaning time spent waiting for jobs goes unpaid:

Sometimes it’s really quiet. It’s not even worth … turning your car on for. Yeah, it’s basically just waiting until … you know there’s going to be demand.

This in turn means no job security. If demand decreases, so does income – exactly what happened to rideshare drivers in the pandemic, with some reporting their incomes had halved or worse.

Rideshare workers’ only communication with their “employer” (their status as contractors is being disputed globally) is through a phone app, meaning interactions take the form of a game, with both parties trying to extract the most money.

Read more:

From COVID anxiety to harassment, more needs to be done on safety in taxis and rideshare services

There is a built-in power asymmetry, however. For example, Uber withholds information about a passenger’s destination and the length of the proposed trip, which could help a driver gauge whether to accept a job.

With no human manager and effectively managed by an algorithm, many interviewees commented on the dehumanised nature of their interactions with Uber and their isolation from other drivers. Classified as independent contractors, they function as individual micro-businesses with no colleagues and no voice or influence in their organisation:

If you’re part of it, then you’re part of it. You know this is how things are going to be. So there’s no point questioning it because there is no human component to it, so there’s no one to question.

On the COVID front line

Because of their status as independent contractors, however, risk mitigation such as masks, sanitiser or plastic screens has been their own responsibility.

While Uber offered a $20 rebate for sanitiser in 2020, drivers reported a difficult application process, with many giving up. Drivers also felt they lacked preventive health education.

On top of increased precariousness and health risks, drivers also faced the consequences of COVID’s polarising effects. They reported picking up anti-mask, unvaccinated passengers, under pressure to accept the rides due to financial anxiety and the threat of poor ratings.

Especially at the beginning of the first COVID happening, a lot of customers didn’t really want to wear a mask … and I was wearing a mask obviously. But there’s some of them tried to reach for my mask and trying to make me take it off and being abusive and all this kind of thing.

If drivers become infected with COVID-19, they often lack the financial resources to cover their household expenses. Their need to keep working then puts the wider community at risk, too.

Risk but few rewards

There have been trade union efforts to organise rideshare and delivery drivers, including an ongoing Employment Court claim seeking employment rights. As contractors, however, drivers are legally barred from full union membership – again denying drivers the means to communicate their grievances.

All of these structural features mean rideshare and delivery workers have been isolated, voiceless and highly vulnerable during the pandemic. Without protections such as sick pay or annual leave, gig workers also cannot choose to work from home.

Read more:

Uncertainty, money worries and stress – gig workers need support and effective ways to cope

But, as some have argued, they are providing what can be regarded as an essential service, putting themselves at risk while delivering food and other goods to customers in isolation.

One of the many lessons of the pandemic is the urgent need for workers in the gig economy to have their voices heard. We all need to be more aware of the precarious and risky working conditions of the person who delivers our takeaways or takes us to a party. And we need to support worker-led collectivisation efforts.

![]()

Leon Salter receives funding from an MBIE Science Whitinga Fellowship.

Mohan Jyoti Dutta receives funding from the Ministry of Justice and the Lottery Grants Board.

– ref. Voiceless and vulnerable, NZ’s gig workers faced more risk with fewer protections during the pandemic – https://theconversation.com/voiceless-and-vulnerable-nzs-gig-workers-faced-more-risk-with-fewer-protections-during-the-pandemic-178747