Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Sasha Grishin, Adjunct Professor of Art History, Australian National University

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Review: Queer, National Gallery of Victoria

Many exhibitions claim to be a landmark show, but few live up to the hype. This one exceeds the hype.

Queer is a beautiful, strange, hard-hitting and challenging exhibition where the central concept is like liquid mercury that, on hitting a hard surface, instantly scatters into innumerable droplets – each perfect in itself.

It is a show about art made by people who consider themselves as queer. In some cases, it is an exploration of gender and sexuality. In others, it is a journey into a sensibility or an interpretation of existing art made by non-queer artists that can be interpreted through a queer perspective.

More specifically, it is an examination of art history through a “queer lens”, art that spans millennia and that is drawn from the fabulously rich collections of the National Gallery of Victoria. The exhibition is not anchored in any specific medium but ranges over many art forms through more than 400 artworks occupying five gallery spaces.

Queerness across millenia

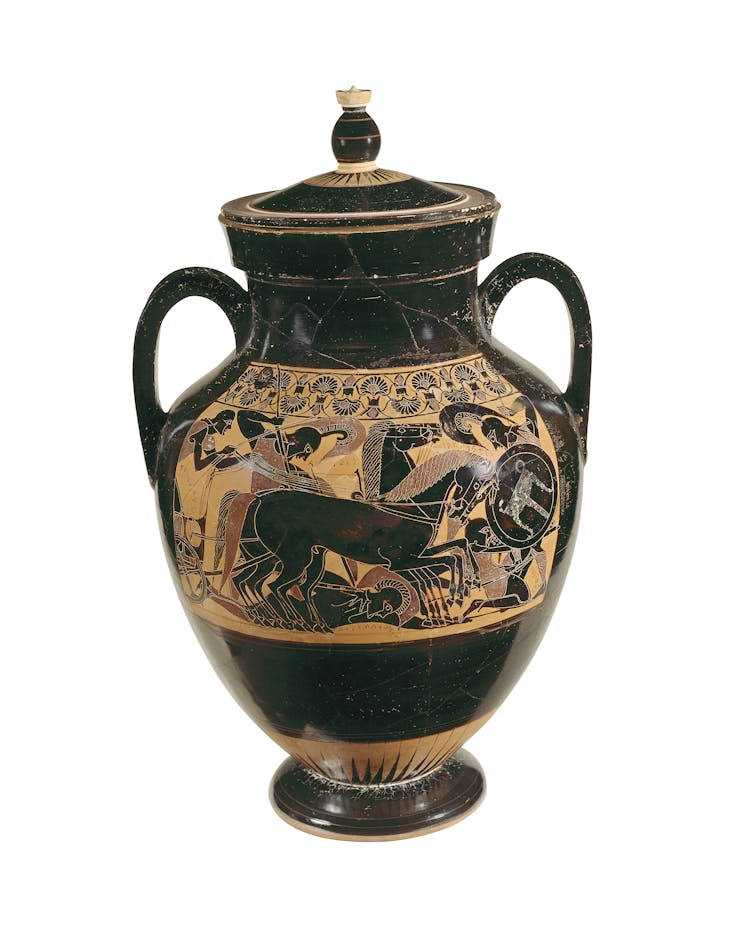

This broad-brush approach to the concept of “queer” has meant that it is possible to include a Greek Chalkidian black-figure vase, 540 BCE, depicting Achilles, the Greek hero of the Trojan War, who, according to some readings of Aeschylus and Plato, took his warrior friend Patroclus as his lover.

In the context of this exhibition, it is an illustration of homosexual love in the ancient world.

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Felton Bequest, 1956

Some 2,500 years later, in a remarkable photograph by Ponch Hawkes, two women embrace in a public display of their affection as part of the 1970s Gay Liberation Movement in Melbourne. Again it is an expression of a gay relationship celebrated through art.

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Purchased NGV Foundation, 2018 © Ponch Hawkes, 2018

In Christian iconography, some characters, including the youthful King David who as a shepherd and harpist slew the giant Goliath, were imbued by some artists with homoerotic qualities, such as in the wondrous painting by Johan Zoffany of 1756.

The making of a queer icon

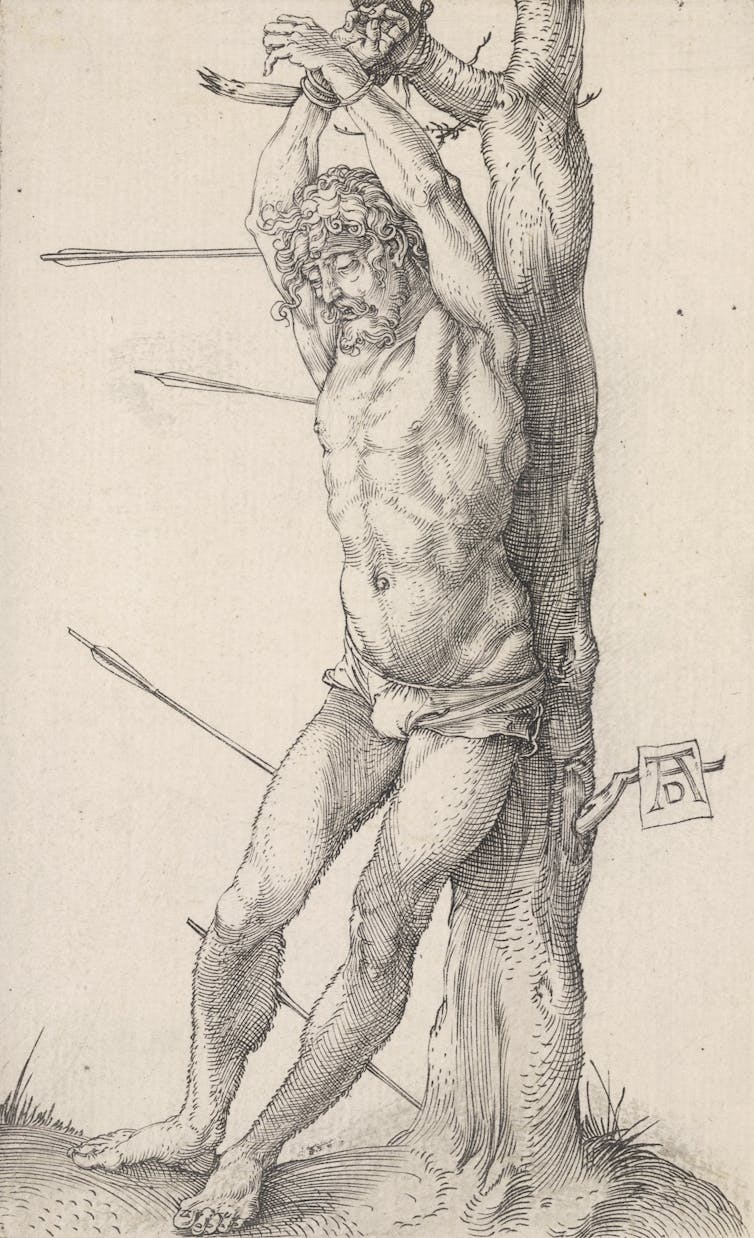

Another example was Saint Sebastian, who was martyred by the Roman emperor Diocletian for his Christian faith and who was frequently shown as a beautiful almost naked youth tied to a tree or pillar and pierced with numerous arrows. Such depictions opened a path to erotic and phallic readings of the imagery.

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Felton Bequest, 1956

Contrary to popular belief, Sebastian survived his experiences as a pincushion and was ultimately clubbed to death after he confronted the emperor over his evil ways. However, it was the saint transfixed by arrows that became his most enduring image and the excuse for artists to explore the beauty of the male nude.

Albrecht Dürer’s magnificent engraving of St Sebastian of 1501 may not have had a queer interpretation at the time of its creation, but by the 19th century, Sebastian had morphed into a gay icon. Oscar Wilde in his French exile took the alias Sebastian Melmoth.

Once the saintly image was freed of its canonical content, Sebastian marched through time attracting rich traditions of interpretation.

The fabulous Louise Bourgeois in her bold and monumental Ste Sébastienne, 1992, recreated the saint as a headless mutilated female who is surrounded by arrows that become a pointed reference to the contemporary persecution of women and a parallel to the historic persecution of Christianity by pagan rulers.

A new reading

One of the highlights of the exhibition is the fabulous costume designs by Leigh Bowery, the Melbourne-born artist, designer and performer, who revolutionised the English art scene in the 1980s making a great impact on Lucian Freud and Boy George.

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Purchased, 1999 © Courtesy of the artist’s estate

Costumes including The Metropolitan (c. 1988) and Pregnant tutu head (1992) scandalised in a subversive manner the conventions of dress and performance art at the time.

Although many of the exhibits document the centuries of struggle for the recognition of queer rights, a queer identity or simply the right to exist as a queer person, the overwhelming prevailing theme of the exhibition is the celebration of love between two people of the same gender.

© the Artist’s Estate. All Rights Reserved / Bridgeman Image

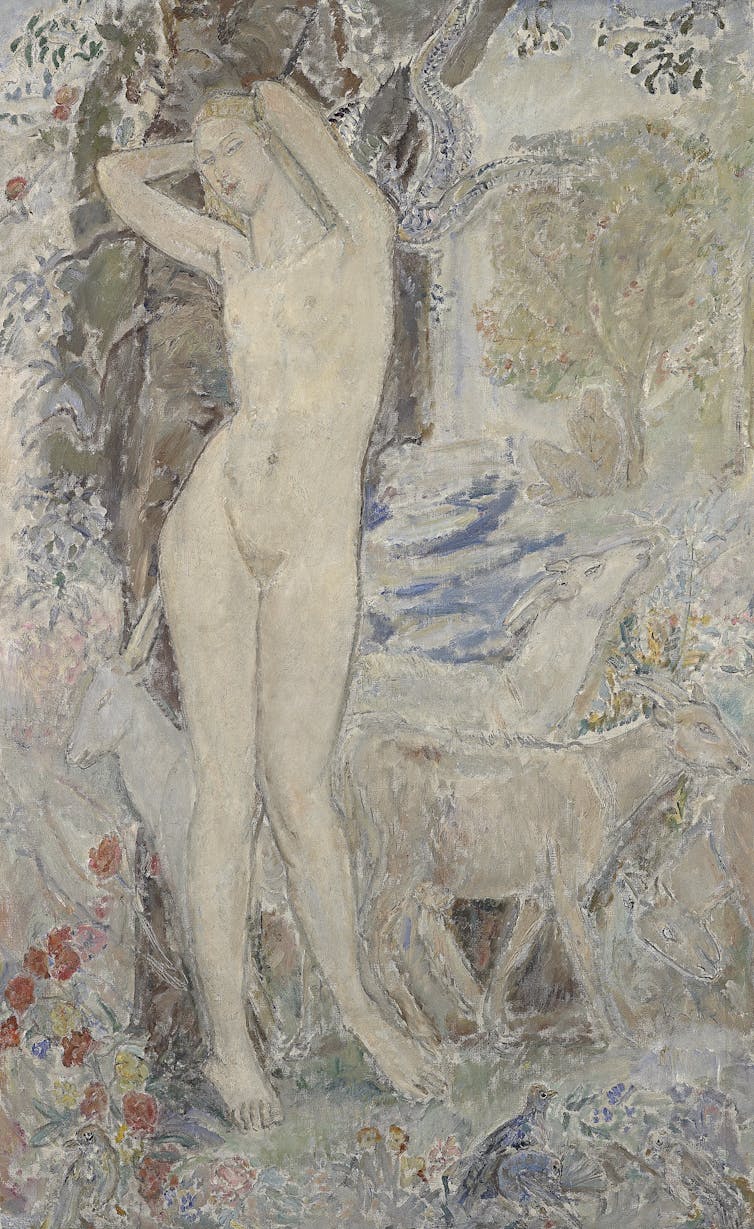

Quite a number of the assembled artworks are familiar to us, including Ethel Walker’s Lilith (c. 1920s) – the image of the first wife of the first man Adam but also possessing the properties of a primordial she-demon.

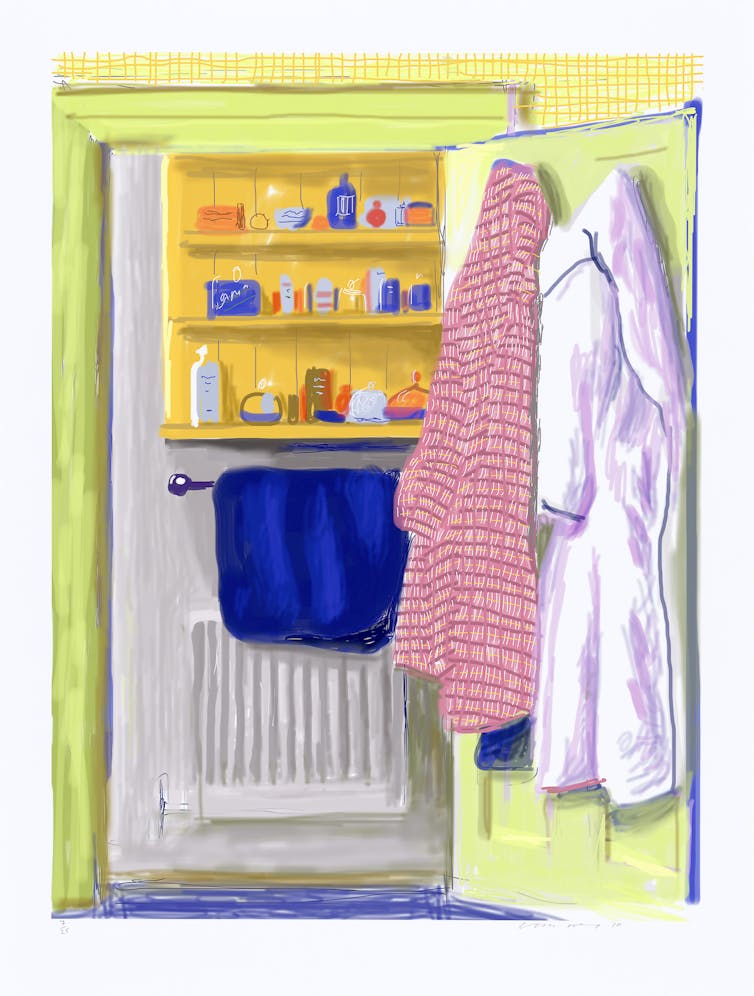

Also Glyn Philpot’s symbolic images, Agnes Goodsir’s celebration of her love for her beloved Cherry, the sensuous images of Janet Cumbrae Stewart and the homoerotic works of David Hockney, James Gleeson and Gilbert & George.

A gift from David Hockney, 2019 © David Hockney

By assembling, for the first time, such a huge cross-section of art with its phenomenal cultural diversity, richness of imagery and exceptional artistic calibre, this exhibition suggests an alternative and viable reading for art history through a queer lens.

The curatorial team responsible for this extravagant exhibition – include the NGV curators Dr Ted Gott, Dr Angela Hesson, Myles Russell-Cook, Meg Slater, and Pip Wallis – all identify with the LGBTQ+ community and present an insider’s view of queer art.

It could be argued that the 20th century was the age of writing women back into a history of art. The opening decades of the 21st century represent an age when the “queer gaze” is presenting a new and alternative reading for art of the past and of the present.

Queer is at NGV International until August 21.

![]()

Sasha Grishin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. ‘This show exceeds the hype’: NGV’s Queer advances a beautiful and challenging reading of the queer gaze in art – https://theconversation.com/this-show-exceeds-the-hype-ngvs-queer-advances-a-beautiful-and-challenging-reading-of-the-queer-gaze-in-art-176005