Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Nick Richardson, Adjunct Professor of Journalism, La Trobe University

Wikimedia Commons

Men write nearly nine in ten sports articles that appear in Australian media, a report on female voices in the media found last year. The report also found women were only quoted in 31% of the most prominent sports stories that are published, and about 31% of sports stories focused on a female subject.

These statistics show that despite an increase in the visibility of a few female sports reporters during the past decade, media coverage of women’s sport is still not fully reflecting its excellence, depth and achievements.

Yet there was a time when this wasn’t the case, when a diverse group of female sports reporters played a critical role in covering women’s sport.

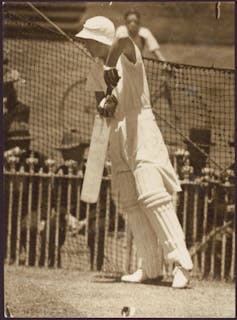

This was perhaps best exemplified in the newspaper coverage of the first test cricket series between the Australian and English women’s team in 1934-35 in Australia, and the subsequent Australian women’s tour of England in 1937.

As I discuss in my new podcast, The Maiden Summer, the series featured coverage by a range of Australian female sports journalists whose reporting helped support the growing public interest in the tests.

Pioneers in sports media

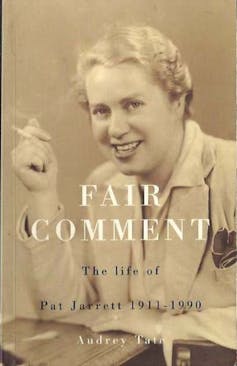

Patricia Jarrett was a talented swimmer and junior athletics champion in Victoria when she became the first female sports writer at Keith Murdoch’s The Herald in 1933.

The Herald’s in-house staff publication introduced Jarrett as “[…] our outstanding woman athlete.” At the time, there was only one other woman on the newspaper’s editorial staff.

Wikimedia Commons

Jarrett then accompanied the 1934-35 Australian women’s cricket team around the country, and became the first woman to cover an overseas cricket tour when she travelled to England in 1937.

These breakthroughs provoked little resistance within newsrooms. Jarrett recalled in a National Library of Australia interview in 1984 there was only one reaction to her being sent on the 1937 tour, when a female friend remarked, “Fancy The Herald sending a woman to England to cover a cricket match.”

But Jarrett explained when she asked Murdoch if she could cover the tour, he readily agreed “…and off I went on this slow boat”.

The arrival of the Australian Women’s Weekly in 1933 also provided an important platform for a discussion about women’s sport. The former cricketer, administrator and national selector Ruth Preddey had a weekly column in the new magazine that canvassed a range of sporting issues, particularly those affecting women’s cricket.

WikiCommons

Jarrett and Preddey were soon joined by many others in Australian sports media:

-

the Hansen sisters, Pat and Carley, who played hockey and cricket, wrote about women’s sport in Sydney and Brisbane newspapers

-

Lois Quarrell, who created the Women in Sport page in The Adelaide Advertiser in 1936 and continued to cover women’s sport in the 1940s and 1950s

-

Gwen Varley, who pioneered the coverage of women’s sport, particularly grassroots sport, during the early years of ABC Radio in Sydney and then at 3AW in Melbourne

-

Kath Commins, a talented cricketer and tennis player, who joined The Sydney Morning Herald in the 1934 after telling an executive there was a gap in the newspaper’s coverage she could fill – women’s sport.

Early advocates for women’s sport

What many of these women had in common was a deep involvement in sport administration. This meant they were not just absorbed by the contests of sport, but also its development and promotion. They became early advocates for women’s sport through their writing and broadcasting.

Melbourne University Press

There were two important factors that feed in to this blossoming of women’s sport reporting in the 1930s.

In cricket, in particular, there was a strong public interest in the game, especially following the 1932-33 men’s Ashes series that was riven by the Bodyline controversy – the use of short and targeted fast bowling by England to curb the run-scoring of Don Bradman. English women’s captain Betty Archdale was still being asked about “Bodyline” when her team arrived in Fremantle in 1934.

Second, women’s cricket was in the midst of the next stage of its evolution – the game was more organised at a state level and there was an equivalent growth in interest. Women’s club cricket in Melbourne would frequently draw several thousand spectators, mainly men, to suburban grounds.

A slow decline after the war

This interest in women’s sport and the growth in female reporting was interrupted by the second world war.

Although there was still some vibrancy in post-war women’s cricket, the number of women sports reporters declined, partly because returned servicemen went back to newsrooms, and partly because some of the trailblazing female reporters from the 1930s had moved on.

Jarrett, for example, had been an accredited war correspondent within Australia, which reflected her desire to write about issues other than sport. She later recalled,

It was when I came back from that [1937] tour that I thought there had to be more for me in journalism than sportswriting […] I saw the opportunities for other writing.

My preliminary research shows publications had supported this group of pioneers at the time because there was a readership for women’s sport. Newspapers, in particular, were also healthy businesses back then. Advertising was strong and there were large editorial departments and plenty of pages to fill – unlike the current commercial pressures facing the Australian press.

Nevertheless, there is only one sobering conclusion to be drawn – we have gone backwards since then.

Integral to appreciating the contribution of these women’s sports reporters in the 1930s is an understanding of how important they were in supporting women’s sport and driving interest, patronage and attendance at games.

This is a clear sign what happened once before needs to happen again – we need more women reporting on sport, especially at a time when the interest in women’s sport has rarely been greater.

![]()

Nick Richardson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Women sportswriters were critical to the growth of cricket in the 1930s. How have we gone backwards? – https://theconversation.com/women-sportswriters-were-critical-to-the-growth-of-cricket-in-the-1930s-how-have-we-gone-backwards-175644