Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Peter Hobbins, Head of Knowledge, Australian National Maritime Museum and Honorary Affiliate, University of Sydney

IMDB

It’s a familiar tale with a morbidly fascinating ending: humans go feral. Emerging from the wreckage of a crashed aircraft or sunken ship, they find themselves cast into a wilderness. Their social moorings lost, the survivors drift towards depravity, chaos and death.

This is the premise for Showtime’s visceral series Yellowjackets, which has just wrapped up its premiere season. Its gruesome depiction of cannibalism and privation seems too horrific to be true. Yet several stories from Australia’s past show fiction can come perilously close to our own realities.

Parallel fates

Yellowjackets tracks two parallel fates. In 1996, a high-school soccer team survives an aircraft accident in a remote Canadian forest. In our present day, those who made it out remain both united and riven by their shared ordeal.

But the survivors share something more traumatic – and unthinkable – than just a plane crash. As the episodes progress, both the plot and the characters disentangle, revealing a narrative of mutilation, murder and cannibalism.

The creators and critics alike have likened Yellowjackets to fiction, especially William Golding’s 1954 novel, The Lord of the Flies. Others draw parallels with the 1972 crash of Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571 in the Andes. Cannibalism sustained some of the survivors who emerged after 72 days of torment, including members of an amateur rugby union team.

Lifeboat dramas and castaway narratives

Yellowjackets collapses several genres of survival narrative. In part it evokes the castaway stories that ask how we sustain our moral, spiritual and intellectual essence in the absence of everyday cultural constraints. The series also echoes the “lifeboat drama”, in which traumatised survivors realise that they depend entirely on each other for their future – or their demise.

In 1929, for instance, celebrated Australian aviators Charles Kingsford Smith and Charles Ulm provoked a tragic scandal. On a flight from Sydney to England, their record-breaking aircraft Southern Cross made an emergency landing in the Kimberley region of Western Australia. They withstood two weeks of extreme temperatures and dwindling supplies before being saved.

But two ill-prepared friends who participated in the search were less fortunate. After an engine failure their small aeroplane, named Kookaburra, landed in the Northern Territory’s Tanami Desert. Pilot Keith Anderson and mechanic “Bobby” Hitchcock had no water aboard.

A poignant diary written by Anderson on the Kookaburra’s tail recorded that the increasingly weakened men drank the only fluids available to them: oil, petrol and their own urine. They soon perished, adding vitriol to accusations that the Southern Cross disappearance was merely a publicity stunt.

State Library Queensland

Another accident in 1937 also left a bittersweet legacy. Flying to Lismore from Brisbane, a Stinson Model A airliner vanished. While a vast search was mounted, three of the seven men aboard survived its crash into the McPherson Range on the Queensland/NSW border.

Believing that he could see a farm in the distance, James Westray set off for help but fell fatally over a cliff. Rather than resorting to cannibalism, however, Joseph Binstead struggled for ten days to keep alive his injured fellow passenger, Jack Proud. When rescued, the pair asked their saviour for the cricket results.

Calamity, mutiny and brutal retribution

Both lifeboat dramas and castaway narratives are deeply anchored in maritime history – with good reason. Archaeologist Martin Gibbs has termed the study of shipwreck survivor camps “the archaeology of crisis”, laying bare the social challenges, survival strategies and rescue plans of those who wash ashore.

Departing Calcutta in 1796 with trade goods for the new British settlement of Sydney, the sailing ship Sydney Cove began sinking and was deliberately beached. Landing on Preservation Island in Bass Strait, its British and Indian crew established a camp and dined on native animals.

But their 17 shipmates who set off to raise the alarm in Sydney suffered desperate privations. Their small longboat was wrecked on Victoria’s Ninety Mile Beach. Struggling for 700 kilometres overland, they faced unfamiliar country and daunting river crossings. The marooned mariners were at first aided by coastal Kurnai and Thaua peoples. Gradually, however, exhaustion, injury, starvation and the baser instincts of people under extreme duress picked them off. Ultimately, only three ragged sailors reached the safety of Port Jackson.

Read more:

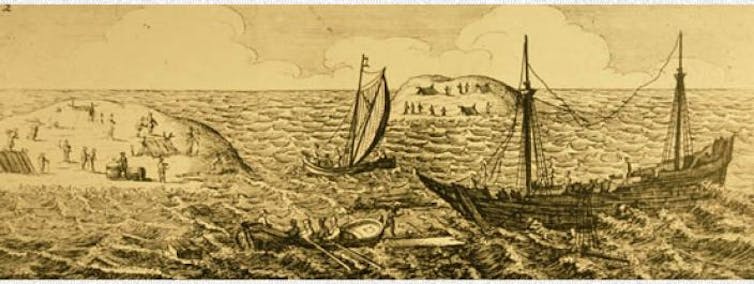

Picturing the unimaginable: a new look at the wreck of the Batavia

The wreck of the Batavia

Where Australian history most viciously parallels Yellowjackets, however, is a series of tiny islands off the Western Australian coast. Here in 1629 a Dutch ship named Batavia pitched up on a coral reef. Its commander, Francisco Pelsaert, departed in a boat with 48 others to seek help. Over 200 crew, soldiers and passengers remained stranded.

Returning over three months later, Pelsaert found that a pitiless mutiny had occurred. It was led by Jeronimus Cornelisz, an officer of the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC), or United East India Company. Prior to the wreck, he had led plans to kill Pelsaert and commandeer the Batavia, including its cargo of silver coins.

WA Museum

Determined to ensure their provisions would last, Cornelisz recruited a cadre who hunted down and slaughtered up to 125 men, women and children. The mutineers drowned, bludgeoned, stabbed and slashed the strongest first, before moving on to the sick and weak. Those who were spared faced rape, sexual slavery, vicious punishment and death. The toll of depravity – including the murder of pregnant women and infants – was every bit as dark as the fictional events in Yellowjackets.

Finally, two groups of survivors remained: the mutineers and the loyal soldiers who had been sent to another island. After several beachside battles, the soldiers captured the feral Cornelisz, who was soon executed.

Perhaps the mutineers’ moral corruption on the Houtman Abrolhos Islands comprised what we could consider the Batavia’s first “series”. If so, the retribution meted out by the VOC would make for an equally brutal season 2.

Yellowjackets might take survival drama to the extreme, but our own episodes of endurance remind us nobody comes out of the woods unscathed.

Yellowjackets streams in Australia on Paramount Plus.

![]()

Peter Hobbins leads the curatorial, library and publications team the Australian National Maritime Museum. Over 2016-19 he was awarded an Australian Research Council DECRA Fellowship to research the history of aircraft accidents and aviation safety in Australia.

– ref. Cannibalism, mutilation and murder: the Australian calamities that rival Yellowjackets for survival horror – https://theconversation.com/cannibalism-mutilation-and-murder-the-australian-calamities-that-rival-yellowjackets-for-survival-horror-174863