Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Michael Swanson, PhD Student, University of Otago

Christopher Luxon’s ascendancy to the National Party leadership has highlighted – once again – the precarious balance between the party’s liberal and conservative wings. So his newly appointed shadow cabinet attempts to establish some equilibrium, particularly in the choice of liberal Nicola Willis as deputy.

But persistent questioning about Luxon’s own evangelical Christian faith tends to reinforce perceptions that National’s “broad church” is not an entirely unified congregation.

These perceptions have their roots in National’s origins as a political party. The question now is, why does this need for balance exist? And why, under MMP, has National not devolved into multiple, more ideologically coherent, parties that negotiate with each other come election time?

To answer those questions we need to look at the formation of National from a merger between the United and Reform parties in 1936. In that history we can see the origins of the modern party and the challenges it faces in the MMP era.

The birth of a party

The United and Reform parties had first formed a coalition in 1931 to see off a challenge from the Labour Party, and won that year’s general election. But in 1935 the coalition lost to Labour, leading to the formal merger as National.

United’s predecessor, the Liberal Party, dominated New Zealand politics up to the first world war, and was the country’s first organised political party. The Liberals enjoyed support from urban liberals and workers, but the formation of the Reform Party in 1909 and Labour in 1916 saw a steady decline in the party’s fortunes.

Read more:

Luxon takes the controls – can the former Air NZ CEO make National straighten up and fly right?

For its part, the Reform Party was the first consolidation of conservative politicians in New Zealand, coming to power for the first time in 1912 and staying in government until 1928.

It’s establishment went back to the Liberal government’s land and welfare reforms, which were branded as “socialism” and an attack on farmers. Support from social conservatives and rural communities continued to be core components of the Reform Party until the 1936 merger.

Meanwhile, a group of Liberal members had formed the United Party in 1927, supplanting the Liberals as the main challenger to the Reform Party. United gained support from urban centres, the business community and socially liberal (in the 1920s sense) interest groups.

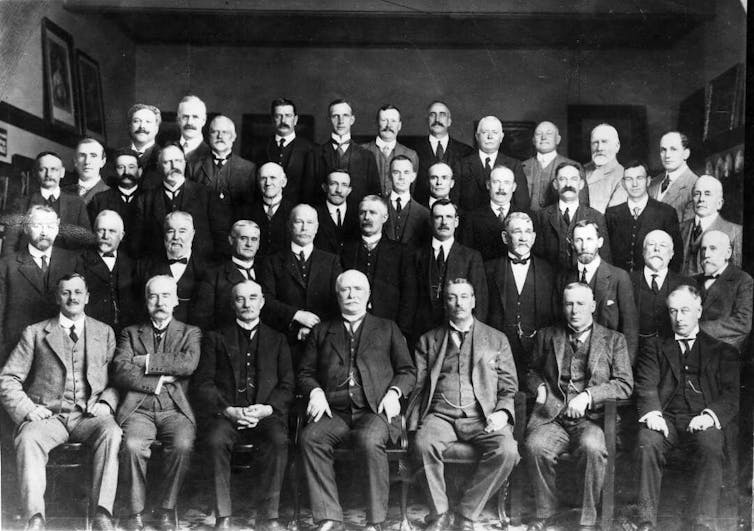

Alexander Turnbull Library, CC BY-NC

The MMP effect

If this all seems oddly familiar, that’s because many aspects of the United and Reform parties still exist within National today.

Under the First Past the Post (FPP) electoral system, the merger of those two parties made sense. Forming a single block that represented the centre-right in New Zealand allowed them to build a well-supported political apparatus.

More importantly, the merger allowed the two parties to stop fighting each other, and instead counter Labour.

Under MMP (which replaced FPP in 1996), however, the need for single parties that dominate whole sides of the political spectrum has decreased. Instead, there’s an opportunity for parties to have more refined policy platforms based on clear ideologies, rather than broad-based appeal.

This doesn’t mean socially conservative or liberal parties can’t work together – MMP allows for this as part of governing coalition negotiations, rather than the tensions playing out as internal party machinations.

Proportional representation systems tend to increase diversity within political systems – not just in terms of gender or ethnicity, but also by providing more specific political channels for different ideological perspectives, and encouraging open collaboration and compromise between those various groups.

Looked at this way, the obvious outcome is for a devolution of major “one size fits all” parties into smaller ones that take clearer policy and ideological positions. To some extent this has already happened on the left, with the advent of New Labour, and subsequently the Alliance (which contained the Green Party), splitting out of Labour in the early 1990s.

No motive for change

So, if that’s the way MMP works, could such a devolution occur within National, and what might that look like? Might we see modern versions of United and Reform – one socially liberal, the other conservative – emerge to represent different groups on the right?

Similarly, could we witness the same process on the left, with socially conservative elements of Labour forming their own party, separate from but aligned to the Labour Party?

It’s not impossible, but for the time being seems unlikely. The main reason for that is scale – staying a single entity gives a party size, and size brings resources. So while devolution might make sense in theory, the current system rewards major political blocs, particularly through campaign funding.

Read more:

Labour makes it easier to change leaders, but Jacinda Ardern has no reason to go – yet

Segmenting into new parties would also result in a splintering of support, with consequences for funding streams. The consolidation of resources and support was, of course, one of the main forces that pushed United and Reform together in the first place.

Unless there’s major fallout within National, with one cohort having severely reduced influence over policy, it’s unlikely there will be significant change any time soon. For decades, National’s liberal-conservative balance has seen the party able to unify a broad base around core values, making National the key player on the centre-right.

Given all of this, until the 2023 election we can expect to hear far more about Christopher Luxon’s conservatism being balanced out by the urban liberal values of Nicola Willis. For now at least, there will be no going back to the future for National.

![]()

Michael Swanson is a member of the National Party

– ref. History made the National Party a ‘broad church’ – can it hold in the MMP era? – https://theconversation.com/history-made-the-national-party-a-broad-church-can-it-hold-in-the-mmp-era-173319