Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Michael Westaway, Australian Research Council Future Fellow, Archaeology, School of Social Science, The University of Queensland

Rio Tinto’s destruction of the 46,000 year old Juukan Gorge rock shelters has led to recommendations by the Parliamentary Inquiry on how Australia can better conserve Aboriginal heritage sites.

Around the time the recommendations were made, Queensland’s Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Act faced an important test when a pastoralist who cleared 500 hectares of bushland at Kingvale Station in Cape York was charged with failing to protect Aboriginal cultural heritage.

The charges were eventually dismissed but the prosecution, the first of its kind in Queensland, highlights weaknesses in the law.

Like related legislation in other Australian states and territories, Queensland’s law requires landholders to conserve Aboriginal heritage sites or risk prosecution.

But the law has been criticised by many Aboriginal people and heritage specialists for allowing destructive development by removing any ability for government to independently assess how proposed clearing would affect Aboriginal heritage.Under the “duty of care” provisions in the Act, Aboriginal heritage must be protected even if it is not known to landholders. However, as the Kingvale clearing case heard, if Aboriginal heritage is not known, how can it be shown to have been lost?

What we learned from the Kingvale clearing case

In 2013, the former Newman government in Queensland removed protection for the environment by introducing the Vegetation Management Act which enabled clearing of what they deemed as “high value agricultural projects” in Cape York.

The World Wildlife Foundation argued this would see large areas of forest and bushland destroyed. Advocates for the new Act argued primary producers are “acutely aware of their responsibility to care for the environment”.

In opening up new areas of Cape York to clearing, this legislation posed new threats to heritage sites. In this context the landholder of Kingvale decided he did not need to assess cultural heritage when clearing 500 hectares.

At the conclusion of the hearing into this case, Judge Julie Dick of the Cairns District Court instructed the jury to return a not-guilty verdict, exonerating the landholder, as the offence could not be proved beyond reasonable doubt.

The landholder’s legal team noted in the media if their defendant had been found guilty, every landholder (including freeholders) who had cleared land, built a fence or firebreak, ploughed a paddock, or built a road or airstrip since 2003 would potentially be guilty of a criminal offence.

The defendant argued the ramifications of the legal case were significant

for the rest of Queensland […] anyone who mowed a lawn or cut down a tree since 2003 would be automatically liable.

In our view, this is hyperbole. Section 21 of the Act makes explicit a person’s right to enjoy the normal and allowed use of their land to the extent they don’t harm Aboriginal heritage.

Further, a person doesn’t commit an offence if they take into account the nature of the activity and the likelihood of it causing harm. Mowing the lawn is quite different to clearing 500 hectares of native vegetation.

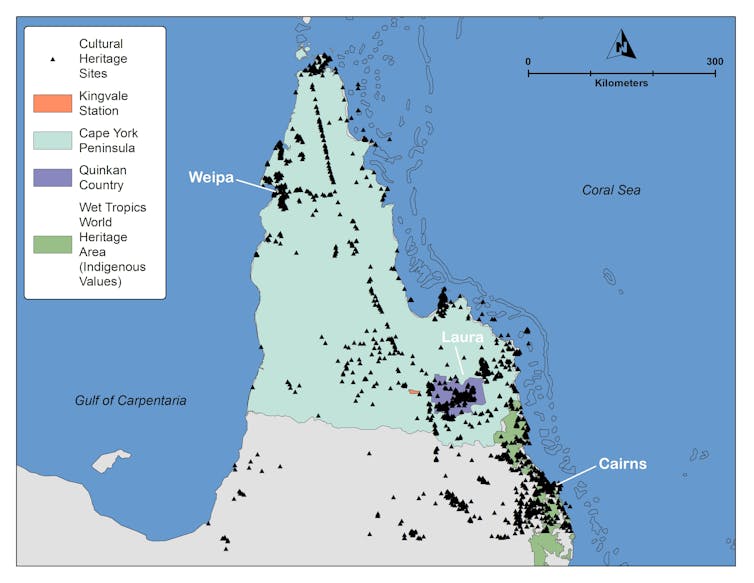

The setting of this activity is also important. Kingvale Station is located 100 kilometres west of the national heritage listed Quinkan Country. Heritage studies in similar landscapes across Cape York have identified scarred trees, artefact scatters, stone arrangements and cultural burial places.

Based on our heritage experience across Queensland, it would be surprising not to find Aboriginal heritage sites at Kingvale.

To reduce heritage risks, we assess the potential impacts of an activity, and talk with relevant Aboriginal groups about their sites and heritage values. Archaeologists and anthropologists also develop models to predict where unknown sites are likely to be found.

Can farming and the conservation of Aboriginal heritage co-exist?

The best way to conserve heritage is for Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians to work together to identify, document, and protect places. An important example is the discovery of human remains from a mortuary tree west of St George, southern Queensland.

The site was discovered during fence clearing by the landholder, who contacted the police. We worked with the landholder who has supported the Kooma nations people to conserve the mortuary tree and enable it to remain on country.

A further example from Mithaka Country saw a spectacular stone arrangement discovered by a pastoral station manager, who notified the native title holders.

All are now engaging with researchers to investigate the site’s history.

Dozens of other examples around the state illustrate collaborative approaches to heritage conservation. But more effective legislation is urgently needed in response to Kingvale’s failed prosecution.

How can we improve cultural heritage protection?

The Juukan Gorge case highlighted how Australia has a problem protecting its Aboriginal cultural heritage. The final report of the parliamentary inquiry into the disaster made several recommendations that could help pave a way forward.

Instances like Kingvale emphasise more work needs to be done. The Queensland government needs to act now to address the glaring problem with its heritage legislation.

Heritage management investment will also help. Victoria provides an example of how to improve Aboriginal heritage management. A standout action is the roll-out of a Certificate IV in Aboriginal cultural heritage management, with over 500 Aboriginal graduates to date.

This program is decentralising heritage management and empowering Aboriginal people across Victoria, building a level of professionalism rarely seen in other states.

Establishing treaties and agreements similar to those in Canada and New Zealand could go a long way to enable First Nations people in Australia to authoritatively protect their respective cultural heritage sites.

Read more:

The Wet Tropics’ wildlife is celebrated worldwide. Its cultural heritage? Not so much

Heritage conservation will remain challenging, particularly in resource-rich states like Queensland. But we can do better.

Judge Dick’s ruling, while frustrating for the effort to conserve heritage, is crucial as it highlights weaknesses in the law.

This trial, along with the Juukan Gorge incident, may represent a critical tipping point in the struggle to protect Aboriginal cultural heritage in Queensland and across Australia.

![]()

Michael Westaway receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Joshua Gorringe is Mithaka Traditional owner and General Manager of Mithaka Aboriginal Corporation RNTBC. Mithaka has received funding from NIAA and QLD Caring for Country Grants. He is affiliated with Mithaka Aboriginal Corporation RNTBC.

Kelsey M. Lowe receives funding from University of Queensland Strategic Research Investment.

Richard Martin receives funding from the Australian Research Council. Richard also receives funding from a range of Aboriginal groups across Queensland relating to native title claims and cultural heritage protection.

Ross Mitchell Kooma Chairperson currently receives funding from NIAA for IPA Ranger Program Murra Murra and Bendee Downs Station owned by Kooma Traditional Owner association Inc

– ref. Australia has a heritage conservation problem. Can farming and Aboriginal heritage protection co-exist? – https://theconversation.com/australia-has-a-heritage-conservation-problem-can-farming-and-aboriginal-heritage-protection-co-exist-170956