Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By John Middleton, Doctoral Candidate, University of Auckland

If you didn’t know Tokelau Language Week begins this weekend, you can probably be forgiven. Spoken by fewer than 5,000 people worldwide, Tokelauan has been designated “severely endangered” by UNESCO, its second-most at-risk category. You simply don’t hear it spoken much – or spoken about.

The statistics tell us why. Since the mid-1960s, migration from Tokelau has meant more 3,000 Tokelauan speakers now live in New Zealand, with just 1,500 still in their homeland. With transmission between generations declining, Tokelauan really is in danger.

Compared to the estimated 1.8 billion English speakers in the world, Tokelauan is literally and figuratively a speck in the ocean, with native speakers now spread around the Pacific in Samoa, Hawaii, Australia and New Zealand.

But while many Tokelauans may not have been born in Tokelau, their culture and language continue to play an important part in their lives. Keeping the language in the public consciousness is crucial to it thriving.

Shutterstock

Survival strategies

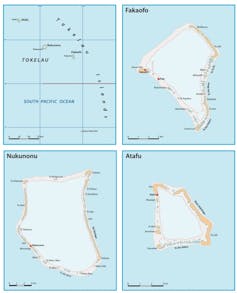

Tokelau itself is comprised of three tiny atolls – Atafu, Nukunonu and Fakaofo – with a combined land area of just 12 square kilometres, a day’s boat ride north-west from Samoa.

To give a sense of scale, the habitable space on Fakaofo is roughly the size of Auckland’s Eden Park. Being so small and near sea level means not only the language is at risk – climate change is a grave threat, too.

Read more:

What happens when a country drowns?

A strong communal culture exists, although many younger people emigrate for education or employment. Fishing the surrounding ocean is vital to people’s livelihoods, as most other supplies have to be shipped in from Samoa.

Now part of the “Realm of New Zealand”, the atolls were first populated over 500 years ago by people originally from Samoa, as evidenced by the similarities between the two languages.

Tokelauan falls under the Samoic-outlier branch of the Polynesian languages, along with Samoan (which it borrows words from) and Tuvaluan. Other related languages include Pukapuka from the Northern Cook Islands, and East Uvea from Wallis Island.

GettyImages

A unique language

On the Tokelauan atolls, the language is used in everyday life, church and politics. For children growing up, it’s the main language they hear all the time, which means inter-generational transfer is normal.

By contrast, only 0.06% of the New Zealand population speaks Tokelauan, almost exclusively within the New Zealand Tokelauan community. In a culture dominated primarily by English, then, how does the language stay healthy and survive?

The answer seems obvious – you speak it. But who, and where? And how do people learn it, if not at home?

One way is through the immersive Tokelauan-speaking preschools in Wellington and Auckland, where most Tokelauans live. Catching children at that critical early age when a language is most easily acquired means they usually gain a full understanding by the age of four or five.

For adults coming fresh to the language, however, it might not be so effortless. Like all languages, Tokelauan has a multitude of unique features. As a linguist, my research is focused on the grammar of Tokelauan and how it differs from other languages.

Do you Tokelauan-speak?

Native speakers have these rules hard-wired naturally in their brains. But for learners, there are various unusual elements of Tokelauan to navigate.

A good example is something linguists call “noun incorporation”, where the noun becomes attached to a verb. In English, there are only a few cases of this: “I went planting trees” can become “I went tree-planting”.

The verb “plant” is connected to the noun “tree” to create the odd compound of “tree-planting”. But this is hardly a regular feature of the language. It would sound weird to say “I car-drove” or “she rugby-played”.

But in Tokelauan, these compounds are completely possible. The sentence “Na tunu e Susie nā ika” (meaning “Susie cooked fish”) becomes “Na tunu ika ia Susie” – “Susie fish-cooked”.

Read more:

Indigenous languages matter – but all is not lost when they change or even disappear

Another interesting linguistic feature is the distribution of “the” and “this”. In English these two words precede a noun – in “the boat” or “this boat”. They can’t appear together, meaning we wouldn’t say “the this boat”.

In linguistics, this is referred to as a “slot” in the grammar that takes either “the” or “this”. But in Tokelauan this one-slot theory doesn’t work; we can have both “te” (the) and “tēnei” (this) together, making “te vaka tēnei” (the this boat). In other words, Tokelauan has two slots – one before the noun and one after it.

These grammatical styles, so different from English and with so many possible patterns, make it a fascinating language to study. Sadly, I don’t Tokelauan-speak. But I’m keen to learn, ideally by visiting those beautiful specks in the ocean while I still can.

In the meantime, Tokelau Language Week is a chance for everyone to appreciate a little of this remarkable and unique tongue that still enriches our shared culture.

![]()

John Middleton receives funding from New Zealand Royal Society Te Apārangi and The Polynesian Society.

– ref. With more Tokelauan speakers in New Zealand than in Tokelau, it remains a unique but endangered language – https://theconversation.com/with-more-tokelauan-speakers-in-new-zealand-than-in-tokelau-it-remains-a-unique-but-endangered-language-169536