Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Jason Bainbridge, Executive Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Design, University of Canberra

DC Comics

Superman is bisexual.

Not the movie-starring, Lois Lane-loving , Klan-fighting, Muhammad Ali-boxing, returned-from-the-dead , mild-mannered man of steel Clark Kent (aka Kal-El, last son of Krypton). But rather his son, Jonathan Kent, named after Clark’s adoptive father and current bearer of the Superman moniker.

Issue #5 of Superman: Son of Kal-El (authored by Melbourne-based writer Tom Taylor) will be out this November, and will feature Jon sharing a kiss with friend and online journalist Jay Nakamura.

Apart from proving Superman has always had a thing for reporters, Jon expressing his sexuality is a watershed moment in the venerable franchise.

Queering the comics

Queer representation has always been read into superhero comics. This may not be surprising: they are a genre composed of essentially-nude-figures-in-action, with same-sex sidekicks and sapphic suggestiveness.

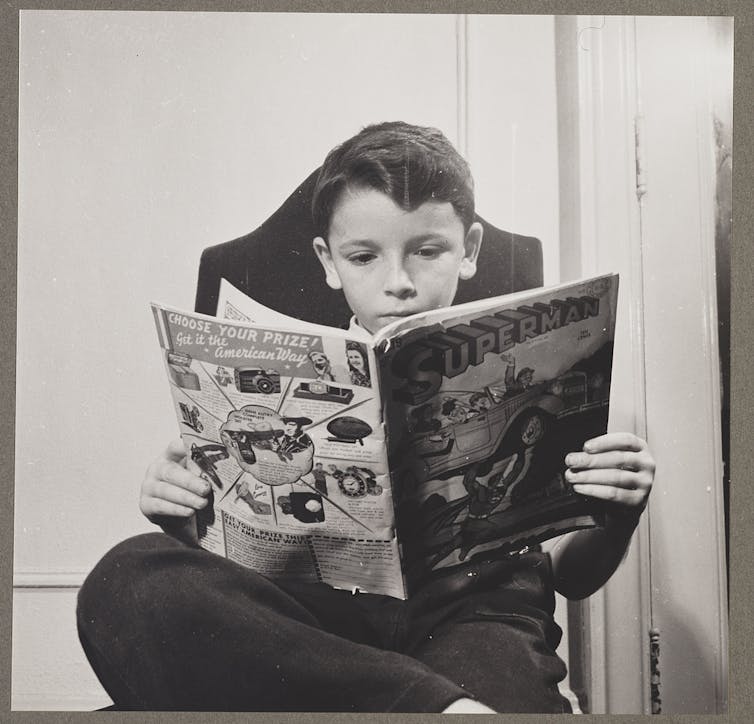

German-American psychiatrist Fredric Wertham believed comics were a corrupting influence. His book, Seduction of the Innocent, argued Batman and Robin’s relationship was inherently sexual, which therefore made comics inappropriate for children.

Library of Congress

His lobbying resulted in the creation of the Comics Code Authority, a censorship body that forbade any mention of homosexuality from 1954 until 1989.

This left secondary characters, like X-Men villains Mystique and Destiny, to be heavily coded as queer – even if their sexual preferences could never actually be stated.

When the code was relaxed in the 1990s, characters who came out as queer were invariably third-tier superheroes (like Alpha Flight’s Northstar, caricatures (like the insultingly effeminate Extraño) or characters in “mature-age” titles (like John Constantine or the Doom Patrol’s non-binary Rebis).

Read more:

How a Canadian superhero brought queer representation to Marvel Comics

Only in recent years have “top-tier” characters like the X-Men’s Iceman, supervillain Loki, Harley Quinn and Poison Ivy, the Kate Kane Batwoman and, in August of this year, the Tim Drake Robin have also come out.

I call these characters “top-tier” because they are known to audiences not only from their comic appearances, but also film, television and cartoon adaptations.

Superman is the most high-profile and visible superhero to express their sexuality in this way.

A social justice superhero

Superman is often assumed to be an unambiguously benign character, particularly in contrast with the more psychologically complex Batman.

But Superman began his career as a crusader for social justice.

In his first issue, he rescues a prisoner from a lynch mob (condemning capital punishment), takes on a wife beater (condemning domestic violence) and takes down a corrupt senator (speaking out against political corruption).

Superman was conceived as a Champion of the Oppressed that millions affected by the Great Depression were crying out for.

Many Superman writers and artists over the years have tried to remain true to these social justice roots.

Look magazine commissioned his creators to produce a two page feature on “how Superman would end the war” on 22 February 1940, nearly two years before Pearl Harbor.

The frequently outlandish Superman comics of the 1950s regularly warned against unbridled scientific experimentation.

John Byrne’s 1980s reboot saw Superman tackle the corporate greed, the power of the mass media and gun violence of the Reagan era.

But in sharp distinction to these portrayals, Superman’s role as the first superhero – and therefore elder statesman of the comics world – frequently saw him presented as a tool of government, rather than a reformer.

In the 1960s’ Justice League of America, he was portrayed as a conservative voice in contrast to more liberal, socially-minded characters like Green Arrow.

Read more:

Superman at 80: How two high school friends concocted the original comic book hero

In Darwyn Coke’s 1950s-set DC: The New Frontier (2004), it is Superman who acts as Senator Joseph McCarthy’s agent in the field, bringing in “rogue” superheroes who refuse to resign.

Perhaps most famously, in Batman: The Dark Knight Returns (1986), Superman appears on behalf of the totalitarian Reaganite government of this parallel 1980s to bring in Batman.

This has created an identity crisis at the heart of Superman, as great as his dual identities of Kal-El and Clark Kent. Is Superman a social justice reformer or conservative Government supporter?

Jon Kent helps to resolve these tensions. Suddenly, we have a Superman who can be truly representative of the 2021 audience, while insulating the elder Superman as a more conservative and paternal figure.

Times of transition

DC Comics

With Superman’s coming out, queer representation has moved from the periphery to become just another component of a superhero’s identity.

Of course, for every reader that celebrates now being able to see themselves in Superman in a way they haven’t before, there will be another bemoaning “bisexual Superman”.

Perhaps it’s worth remembering comic book superheroes were born and enjoy their greatest popularity during times of transition and uncertainty: economic crisis, armed conflict or political precarity. There’s no reason why expressing one’s sexual identity cannot similarly be understood as one of these moments of transition and uncertainty.

In this way, Jon Kent expressing his bisexuality is just as true to the legacy of Superman as Clark Kent’s social justice crusade 82 years ago.

![]()

Jason Bainbridge does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. The queer subtext of Superman comics has long been suppressed. Here’s to the original justice defender coming out – https://theconversation.com/the-queer-subtext-of-superman-comics-has-long-been-suppressed-heres-to-the-original-justice-defender-coming-out-169730