Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Ted Snell, Honorary Professor, Edith Cowan University

Underneath/Uncovered – Rebecca Mansell

Communities are built from a complex layering of influences.

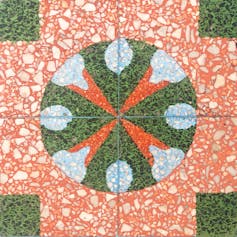

Fremantle Walyalup, like many towns across Australia, is like a terrazzo floor made up of the contributions of the many cultural groups that live here. These rich fragments combine into a cohesive pattern over time, with each element bringing its own flavour, nuance and colour to the amalgam.

Underneath/Overlooked is the latest homage to terrazzo’s popularity in Australia. It follows the contemporary works of Ukrainian-Australian artist Stanislava Pinchuk at Heide and the devotion shown to the terrazzo texture on popular home renovation television shows, design blogs and furniture designs.

Read more:

Don’t forget the west: mid-century modern and David Foulkes Taylor

The Italian connection

One of the more vibrant components of the Fremantle Walyalup terrazzo is the Italian contribution.

The first Italians arrived in the early years of European occupation, their community building in waves as groups sought refuge from famine, political upheaval and war. Fishermen from Capo d’Orlando, Molfetta and Calabria found a new home and built a community that soon attracted others. So, when Guiseppe and Anna Scolaro arrived in 1948 seeking a better life for their young family, they settled in Fremantle.

Underneath/Overlooked

With the skills developed in his small mechanical business in Capo d’Orlando, Guiseppe began making terrazzo tiles to meet the needs of the post-war building boom, establishing the Universal Terrazzo Tile company in 1952.

In Victoria, De Marco Brothers Terrazzo Granolithic and Concrete Placing was established in 1914 by Italian brothers Annibale and Severino De Marco. They completed flooring for the Australian War Memorial’s Hall of Memory in 1955.

Using marble chips imported from Italy, the Scolaros designed tiles to be laid in renovated homes and newly constructed buildings alike.

Supplied

Tradition

Venetian artisans began constructing decorative, durable and easily maintained flooring for their terraces (terrazzo) in the 15th-century, using discarded marble offcuts set within a coloured, concrete matrix.

Abraded and polished to create a smooth finish it was a low-cost solution with a decorative embellishment.

The popularity of terrazzo grew in the early 20th century with new grinding and production technologies. As the Italian diaspora spread around the globe, it was used extensively in public and domestic buildings.

Rebecca Mansell

Read more:

Design makes a place a prison or a home. Turning ‘human-centred’ vision for aged care into reality

Covered with carpet

Terrazzo enlivened many homes and offices built in Western Australia from the 1950s until the 1970s. The floors injected a cosmopolitan modernism into the built environment and generated a familiar ambience for the Italian community. Easily maintained, decorative floors were the perfect blend of the traditional with the aspirational.

Over time, these flamboyant floors fell out of favour and were covered over with carpet, forgotten until new families took up residence and discovered the hidden treasures below.

When visual artist Penny Bovell moved into a new studio in 2000, the intricate and ornate tiles were a revelation.

“The repeat patterns, contrasting colours, textual aggregates, and aged patinas become an intensely expressive language,” she explains.

It was the catalyst to discover more. She bought the Scolaro’s first home and found each room with a unique flooring character. On a quest, she set to find other houses and meet their besotted owners who lived each day with this wondrous bounty.

Rebecca Mansell

Recreating magic

The Underneath/Overlooked exhibition at the Moores Building in Fremantle, presented as part of the Ten Nights in Port festival, is Bovell’s tribute to Guiseppe, Anna and their artistry.

Bovell and daughter, Gabby Howlett, had to find innovative ways of translating the unique presence of these environments into a public gallery.

Rebecca Mansell

Set within the lofty main space within this heritage building, they have recreated the Scolaros’ first home. Printed on silk with the patterns of the various tile layouts of each room, the half-scale floating reconstruction is transformed into a magical space.

Panoramic photographs of floors from other houses activate the walls. On the floor, stacks of tiles printed on foam core can be rearranged to create new pattern variations.

This exercise brilliantly replicates Guiseppe and Anna’s working methodology. Each new client was offered the chance to create a unique pattern using combinations of templates and colours.

Speaking at the exhibition opening, their son Armando said his parents would lay out tiles, chat about colours and develop a floor that had its own character and reflected the preferences of the commissioning patrons.

Old floors, new custodians

The project is a social document. It chronicles the impact of Italian migration to Australia and documents the individuals who made and commissioned these remarkable floors and the new custodians who discovered the bounty beneath their feet.

Underneath/Overlooked

As home owner Stephanie Hammill notes in the exhibition catalogue, the floors are “a precious resource linking different generations and populations. They help us to define us as a community: who we are and where we come from”.

Terrazzo was reinvigorated around 2017 when it was named an official Pinterest trend. Since then, it has become ubiquitous in magazines, on screens and stores.

Like all trends, the current interest will fade — unlike these marvellous floors and the Scolaro legacy.

Underneath/Overlooked is on until Sunday July 25th.

![]()

Ted Snell does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Layer upon layer: uncovering the terrazzo treasures of the west and celebrating legacy floors – https://theconversation.com/layer-upon-layer-uncovering-the-terrazzo-treasures-of-the-west-and-celebrating-legacy-floors-164635