Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Jason Mazanov, Adjunct Senior Lecturer, School of Business, UNSW-Canberra, UNSW

Another Olympics is upon us, inexorable even in the face of COVID. With it comes the inevitable, salacious speculation around doping scandals.

There have been doping scandals at every Olympics in my lifetime and a few before, reaching back to the middle of the 20th century. Now, because of the lag between new drugs coming into sport and the development of reliable drug tests, there’s a 10-year retrospective testing window. This leaves the question of exactly who wins what an open question for a decade.

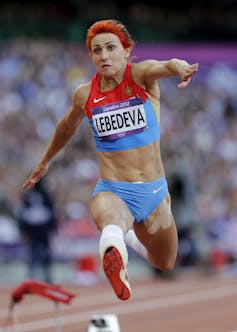

With the testing window used for the 2012 London Olympics now closed (it used to be eight years), we only now have a final account of both medals and doping at those games.

According to Olympics historian Bill Mallon, more than 140 athletes were banned or disqualified, including 42 medallists (13 of which were gold). Nearly half were caught using retrospective testing.

Because doping has become so much a part of the Olympics, one wonders whether the inevitable doping scandals in Tokyo will be as earth-shattering as they once were, or whether the public will merely shrug.

How many positive tests come back every year

The anti-doping industry has become a lot better at what it does since the establishment of the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) in 2000 and the introduction of the World Anti-Doping Code (WADC) in 2001. Revisions to the WADC came into force in 2009, 2015 and 2021.

WADA has invested US$83 million (A$112 million) in developing more advanced drug-testing capabilities since 2001, and US$3.6 million (A$4.8 million) on doping prevention research since 2005.

Read more:

Why drug cheats are still being caught seven years after the 2012 London Olympics

With the Tokyo Games expected to cost an official US$15.4 billion (A$20.8 billion) to stage (with audits suggesting the true figure is at least US$25 billion or A$33.8 billion), however, the amount of money WADA has spent on research since 2001 seems modest.

Despite this investment, the rate of positive tests has remained fairly stable.

The most recent figures released by WADA in 2019 showed the proportion of “adverse analytical findings” (the technical term for positive drug tests) relative to the total number of tests conducted wobbling between 0.97% (2019) and 1.32% (2016).

Athletes and their support teams know the drug-testing game well. They can use the lag between a new performance-enhancing drug being developed, that drug being prohibited and a reliable test being developed to their advantage. It’s just one factor coaches and other support personnel take into account when managing how their athletes use different drugs.

Unless there is a complete game-changer in anti-doping efforts — like a fundamental shift in drug-testing technology — we can reasonably expect an Olympic year to result in the same level of “adverse analytical findings” as any other year.

That means athletes will most likely be caught doping in Tokyo. Just how many — or how long it will take — remains to be seen. With the retrospective testing window, the final medal and doping tallies will only be known in the second half of 2031.

How sport has become more punitive

While drug testing has become more sophisticated, most of the changes to the World Anti-Doping Code since 2001 have actually been to bolster penalties for acts indirectly related to the taking of performance-enhancing drugs (what are known as “non-analytical” rule violations).

There are only two anti-doping violations in the code directly related to drugs being found in an athlete’s body.

By comparison, there are now nine others that deal with indirect violations. These include not being where you said you would be three times for out-of-competition drug tests, associating with someone under sanction for violating an anti-doping rule, and discouraging someone from reporting potential violations to authorities.

In many cases, these types of violations have seen athletes and support personnel vilified and stigmatised as “drug cheats” despite no direct evidence they have ever used a prohibited substance or method.

Last year, for instance, the US sprinter Christian Coleman was given a two-year ban after missing three out-of-competition drug tests in a year. The Court of Arbitration for Sport reduced the ban to 18 months, noting it believed Coleman did not dope and did not avoid being tested. Nonetheless, he will still miss the Tokyo Olympics as a “drug cheat”.

All of these rules have made life much harder for athletes, but their impact appears to be fairly minimal in reducing interest in performance-enhancing drugs.

According to the most recent report by WADA (which gives data only up to 2018), only 283 athletes were sanctioned for “non-analytical” rule violations that year, compared to 2,771 athletes for violations directly related to ingesting drugs.

Learning to live with doping?

The obvious question is whether we just have to live with a certain amount of doping in sport. Given the last time an Olympics was without a doping controversy was the middle of the 20th century, it would seem so.

David J. Phillip/AP

That does not mean we should stop protecting the integrity of sport. Rather, it is a recognition that anti-doping is just one part of this effort.

As an international leader in anti-doping measures, Australia established Sport Integrity Australia last year to replace the standalone Australian Sports Anti-Doping Authority. This move explicitly recognises that doping is part of a much bigger picture that includes match fixing and abuse of athletes.

The greater scandal is perhaps that so little money is invested in anti-doping and sport integrity. Sport Integrity Australia is budgeted to cost Australian taxpayers A$27.4 million (US$20.2 million) in 2020-21, compared to the eye-watering amount of money that goes through Australian sport and recreation every year (A$19.7 billion or US$14.5 billion for 2019).

So, it remains to be seen exactly how much attention the inevitable doping scandals at the Tokyo Games will attract. My main worry is doping scandals have become business-as-usual, one-day dramas in the sporting spectacle that is the Olympics, and little else. As such, I suspect every positive COVID test will generate far more interest than a positive drug test in Tokyo.

![]()

Jason Mazanov has received funding from the Australian Anti-Doping Research Programme and the World Anti-Doping Agency Social Science Research Grants programme in the past. Jason also reviews anti-doping social science research grant applications for a number of international agencies.

– ref. Doping has become inevitable at the Olympics. And who wins gold in Tokyo might not be certain until 2031 – https://theconversation.com/doping-has-become-inevitable-at-the-olympics-and-who-wins-gold-in-tokyo-might-not-be-certain-until-2031-163881