Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Jan Gothard, Adjunct Associate Professor, Murdoch University

Artist: Marcus Fernihough, Author provided

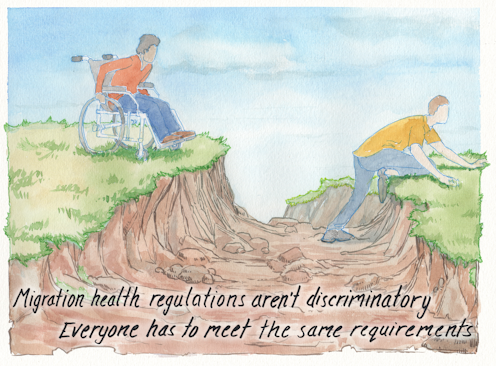

“Idiots”, “imbeciles”, the “feeble-minded”, anyone with a “loathsome disease”: all were refused entry into Australia under early migration acts. Today, the language has changed, but the thrust of migration health regulations has not.

The government has strict health regulations for migrants for three main reasons: to protect public health, preserve access to scarce resources such as organ transplants, and control government spending on community and health services.

While few disagree with the first two, the focus on cost to the community is problematic. This has been used to prevent people with disabilities from becoming permanent residents, even Australian-born children such as Kayaan Katyal, Shaffan Butt or Kayban Jamshaad.

The Racial Discrimination Act of 1975 outlawed raced-based discrimination in migration. By contrast, the Migration Act of 1958 is exempt from the provisions of the Disability Discrimination Act, passed in 1992.

Australia has also excluded itself from compliance with some aspects of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disability to allow it to maintain its discriminatory migration practices.

How do the current health regulations work?

Migration health policy requires visa applicants to be assessed to ensure their future costs to community services will not exceed the so-called “significant” threshold of A$49,000, measured over a specified period depending on the type of visa and health issue.

Some visas in the family and employer-sponsored area allow an applicant to argue for the health requirement to be waived because of personal circumstances and their ability to contribute to society.

Other visas have no waiver, such as investment visas. An investor worth millions who has a child with a disability has no capacity to argue for a waiver; nor does an elite sportsperson, scientist, or academic offered permanent employment. The benefits an applicant brings have no bearing if there is no waiver.

Read more:

Visa policy for overseas students with a disability is nonsensical and discriminatory

If a visa applicant is eligible for a waiver, it can still take years for a visa to be granted, usually at considerable personal and financial cost.

Shaffan Butt was born in Australia in 2014 with a disabling condition that makes the prospect of a flight life-threatening. His family applied for a permanent visa in early 2016, but could not apply for a waiver, despite Shaffan’s perilous circumstances.

They were refused by the Administrative Appeal Tribunal in 2019 since Shaffan’s health care costs exceeded the “significant” threshold. The family is still seeking a response to their appeal from the immigration minister. In limbo for more than five years, their anguish has been enormous.

How many people are affected?

According to statistics provided to me by a home affairs spokesperson, over 99% of the nearly 900,000 applicants who undertook a visa health examination in 2019–20 met the requirement. Only 1,300 people did not, about half of whom had no access to a waiver and were refused outright.

Of the 639 who were eligible for a waiver, 91% were granted visas, but only after years in limbo. Just 84 waivers were ultimately refused.

While these numbers may be small, the personal cost to individuals — both those refused and those subjected to the waiver process — is beyond measure.

As one highly qualified applicant for permanent residence told the Welcoming Disability campaign, which is advocating for change:

the heart of the process is proving to the government that you’re worth more to the country than the cost of your treatment […] because of my disability I had to do more than others to be allowed the right to stay indefinitely.

What does it take to satisfy the minister?

In 2011, the Enabling Australia report recommended many changes in the health requirements for migrants. This included giving all visa applicants access to the waiver and the opportunity to argue for the benefits they can bring to society and their capacity to mitigate costs.

Some positive recommendations have been implemented. Notably, applicants for humanitarian visas are now automatically granted a waiver for the health requirement. But most recommendations have been ignored.

One policy the report recommended be dropped was the “one fails, all fails” rule, which requires all members of a family to meet the health requirement, even if they are not applying to migrate themselves.

This can have particularly bizarre implications. For example, one person I’ve worked with in my role as a migration agent, a Filipino woman named Juliet (a pseudonym), divorced her first husband and remarried an Australian while living in Australia on a temporary visa. Her two teenage children from her first marriage live in the Philippines, and though Juliet supports them financially, they are happily settled there and not applying to migrate.

But in order for Juliet to apply for a permanent visa, her children in the Philippines were subjected to a migration health assessment. Her daughter, who has a mild disability, failed the test. It took three years to satisfy the minister that her daughter’s costs to the community would be nil and grant her visa.

The government’s 2012 response to Enabling Australia accepted the recommendation to drop the “one fails, all fails” rule. But this change has still not been introduced.

True cost to the community

Canada once had similar regulations to Australia, but the government reexamined the need for them several years ago.

The government first assessed the cost impact of those denied visas, which was found to be “minuscule” — just 0.1% of Canada’s annual health care budget.

Adrian Wyld/The Canadian Press/AP

After easing the restrictions in a trial period from 2018, the government found the country was not flooded with the sick and disabled. In April, the changes became permanent.

Read more:

Finally, some changes to health-based discrimination in Canadian immigration law

Australia, too, needs to determine the actual cost of relaxing the health requirement. In the meantime, every visa applicant should be given the right to argue for a waiver, while Australian-born children like Shaffan should be granted a waiver automatically.

It’s time Australia embraced a 21st century understanding of disability and reformed its immigration system to make it more humane.

![]()

Jan Gothard is an adjunct associate professor at Murdoch University. She is a registered migration agent (MARN 1569102) with Estrin Saul Lawyers, specialising in health and disability, and is a co-founder of Welcoming Disability which supports changes in migration health laws.

– ref. Australia once rejected ‘feeble-minded’ immigrants. While the language has changed, discrimination remains – https://theconversation.com/australia-once-rejected-feeble-minded-immigrants-while-the-language-has-changed-discrimination-remains-158872