Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Htwe Htwe Thein, Associate professor, Curtin University

STRINGER/EPA

Myanmar’s democracy movement wants the international community to get tough on the military junta. But if history is any indicator, that’s not going to happen.

Western nations have responded with suspending arms sales and “targeted sanctions” aimed at hurting individual members of the military elite. But for Myanmar’s regional neighbours it’s still largely business as usual.

Australia’s position is emblematic.

Normally it would be expected to follow the lead of friends and allies such as the US, Britain, Canada and the European Union. They have prohibited dealings with businesses controlled by Myanmar’s military, and targeted key junta officials and their families through asset freezes and travel bans.

But citing “national interest”, Australia has declined to follow, on the basis no other countries in the region are taking such measures.

Which is true. At their meeting in Jakarta in April, the leaders of the Association of Southeast Nations (ASEAN) – of which Myanmar has been a member since 1997 – backed “constructive engagement” and “constructive dialogue”. This echoes the stance taken through Myanmar’s previous two decades of military rule.

AP

China, meanwhile, has said it supports Myanmar “choosing a development path that suits its own circumstances”. Its veto power on the UN Security Council makes any global consensus on sanctions unlikely.

Read more:

Aung San Suu Kyi trial: how Myanmar’s judicial system is stacked against the deposed leader

Sanctions in the past

We’ve been through all this before, from the time the US and European Union imposed sanctions against Myanmar in September 1988, following the military’s brutal suppression of democracy protests known as the 8888 uprising.

After thousands of civilians were killed, the Reagan administration suspended all aid and arms sales. More sanctions came with subsequent developments – the coup d’tat that established the junta known as the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC), the house arrest of democracy leader Aung San Suu Kyi in 1989, the refusal to hand over power to the Suu Kyi-led National League for Democracy following elections in 1990, and so on.

In 1996 the Clinton administration suspended visas for “persons who formulate, implement, or benefit from policies that impede Burma’s transition to democracy”, and in 1997 banned US businesses making new investments in Myanmar. In 2003 the US Congress banned imports from Myanmar and prohibited US nationals from providing financial services to the country. In 2008 it banned imports of any jadeite and ruby originating from Myanmar.

To varying degrees other Western nations followed suit. The European Union, for example, imposed an arms embargo and visa bans on top-ranking military personnel and their families in 1996. It then banned imports of timber, metals and precious stones from Myanmar in 2007.

Australia supported such measures with restrictions on financial transactions and visa and travel bans on top-ranking officials, though never prohibited trade and investment relations.

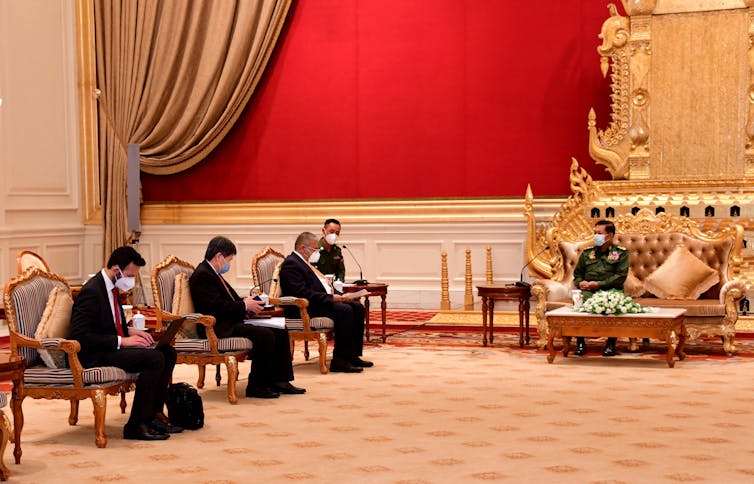

Myanmar Ministry of Information/EPA

Business as usual

But for Myanmar’s Asian neighbours it was business as usual.

China forged a closer, if sometimes tense, relationship. ASEAN talked about “constructive engagement”. When it welcomed Myanmar into the fold in 1997, Malaysia’s prime minister Mahathir Mohamad explained: “We can’t wait until they put their house in order before admitting them.” In the assessment of human rights scholars such as Catherine Shanahan Renshaw: “The influence of ASEAN was negligible in encouraging Myanmar’s transition to democracy.”

Thus Asian business investment in Myanmar increased, seizing opportunities left untapped due the sanctions of the US and others.

In this context, critics thought the sanctions pointless. Leon Hadar of the libertarian US Cato Institute, for example, argued in 1998 that “unilateral trade and investment sanctions” had been a failure on all fronts.

International trade unions and human rights organisations disagreed, arguing the sanctions were important pressure points for improving human rights in the country.

Even so, most observers recognised broader sanctions such as bans and restrictions on imports from Myanmar had wreaked “collateral damage” on the very people they were meant to help. A US state department analysis in 2004 estimated the 2003 import ban had led to the loss of 50,000 to 60,000 jobs in Myanmar’s garment manufacturing industry.

Sanctions in 2021

Is it possible to do better this time – for the US, Europe and a few other countries to more effectively target the regime without hurting the people of Myanmar?

We believe it is.

First, the Americans, British and Europeans have great influence over the global financial system. As noted by Human Rights Watch:

Sanctions imposed by the US, UK, the EU, and other jurisdictions can have extremely broad international consequences. The majority of the world’s financial institutions and banks are based in these jurisdictions, have shares that are traded on their securities exchanges, or otherwise have connections that make them subject to relevant sanctions or regulations enforcing them.

The United Nations special rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, former US congressman Thomas Andrews, has suggested the US ban on financial dealings with junta leaders means any non-US bank or other entity could face criminal and civil penalties if they “wilfully facilitate US dollar transactions” that benefit the Myanmar regime.

Even without China’s support, there is much that can be done to financially isolate Myanmar’s junta.

The second reason is the pressure that civil society – human rights activists and so on – can now put on on multinational corporations. Companies already feeling such heat for links with military companies in Myanmar include the South Korean steel maker POSCO and Indian resources giant Adani Group.

The alternative government formed by deposed parliamentarians wants all foreign companies to stop dealing with the regime, including suspending all payments to the regime.

A prime example is the Myanmar Oil and Gas Enterprise, a state-owned enterprise that provides Myanmar’s government an estimated US$1.5 billion a year. Its foreign partners include Chevron (US) and Total (France).

Cutting off the regime’s access to money will weaken the military’s grip on power. Even with collateral damage, it is “constructive disengagement” that the people of Myanmar are actually asking for in their struggle to restore their fledgling democracy.

![]()

Htwe Htwe Thein has received funding for Myanmar research from the Australian Research Council.

Michael Gillan has received funding for Myanmar research from the Australian Research Council.

– ref. Sanctions against Myanmar’s junta have been tried before. Can they work this time? – https://theconversation.com/sanctions-against-myanmars-junta-have-been-tried-before-can-they-work-this-time-158054