Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Anna Johnston, Associate Professor of English Literature, The University of Queensland

In this series, we look at under-acknowledged women through the ages.

Eliza Hamilton Dunlop’s poem The Aboriginal Mother was published in The Australian on December 13, 1838, five days before seven men were hanged for their part in the Myall Creek massacre.

About 28 Wirrayaraay people died in the massacre near Inverell in northern New South Wales. Dunlop had arrived in Sydney in February, and the Irish writer was horrified by the violence she read about in the newspapers.

Read more:

How can we achieve reconciliation? Myall Creek offers valuable answers

Moved by evidence in court about an Indigenous woman and baby who survived the massacre, Dunlop crafted a poem condemning settlers who professed Christianity but murdered and conspired to cover up their crime. It read, in part:

Now, hush thee—or the pale-faced men

Will hear thy piercing wail,

And what would then thy mother’s tears

Or feeble strength avail!Oh, could’st thy little bosom

That mother’s torture feel,

Or could’st thou know thy father lies

Struck down by English steel

The poem closed evoking the body of “my slaughter’d boy … To tell—to tell of the gloomy ridge; and the stockmen’s human fire”.

The graphic content depicting settler violence and First Nations’ suffering made Dunlop’s poem locally notorious. She didn’t shrink from the criticism she received in Australia’s colonial press, declaring she hoped the poem would awake the sympathies of the English nation for a people who were “rendered desperate and revengeful by continued acts of outrage”.

An early life as a reader

Dunlop, the youngest of three children, was born Eliza Matilda Hamilton in 1796. Her father, Solomon Hamilton, was an attorney practising in Ireland, England and India. Her mother died soon after Dunlop’s birth, and she was brought up by her paternal grandmother.

Part of a privileged Protestant family with an excellent library, Dunlop grew up reading writers from the French Revolution and social reformers such as Mary Wollstonecraft.

In her teens, Dunlop published poems in local magazines. An unpublished volume of her original poetry, translations and illustrations written between 1808 and 1813 reveals her fascination with Irish mythology and European literature. She was deeply interested in the Irish language and in political campaigns to extend suffrage and education to Catholics.

Milson Family Papers – 1810, 1853–1862, State Library of New South Wales, MLMSS 7683

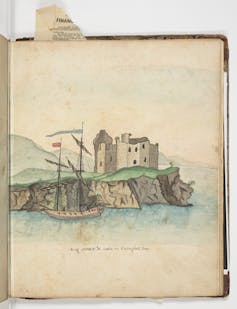

In 1820, she travelled to India to visit her father and two brothers. The journey inspired poems about colonial locations — from the Cape Colony (now South Africa) to the Ganges River — that explored the reach and impact of the British Empire.

In Scotland in 1823, she married book binder and seller David Dunlop. David’s family history inspired poems such as her dual eulogy, The Two Graves (1865), about the bloody suppression of Protestant radicals in the 1798 Rebellion, during which David’s father Captain William Dunlop had been hanged.

The Dunlops had five children in Coleraine, Northern Ireland, where they were engaged in political activity seeking to unseat absentee English landlords, before leaving Ireland in 1837.

Settler poetry and politics

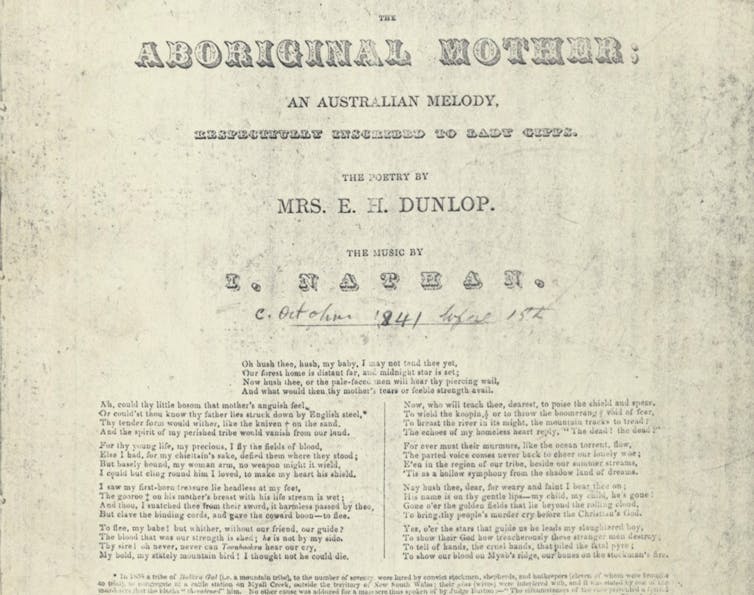

When The Aboriginal Mother was published as sheet music in 1842, set to music by the composer Isaac Nathan, he declared “it ought to be on the pianoforte of every lady in the colony”.

Trove

Dunlop often wrote about the Irish diaspora in poems which were alternatively nostalgic and political. But she also brought her knowledge of the violence and divisiveness of colonisation, religion and ethnicity to her writing on Australia.

Her optimistic vision for Australian poetry encouraged colonial readers to be attentive to their environment and to recognise Indigenous culture. This reputation for sympathising with Indigenous people — and her husband’s arguments with settlers in Penrith about the treatment of Catholic convicts — were widely criticised in the press.

This affected David’s career as police magistrate and Aboriginal Protector: he was soon moved to a remote location. There, too, local landholders campaigned against his appointment and undermined his authority.

Indigenous languages

When David was posted to Wollombi in the Upper Hunter Valley, Dunlop sought to expand her knowledge of Indigenous culture, engaging with Darkinyung, Awabakal and Wonnarua people who lived in the area.

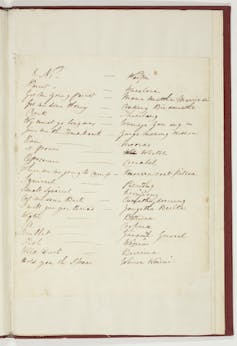

She attempted to learn various languages of the region, transcribing word lists, songs and poems, and acknowledging the Indigenous people who shared their knowledge with her.

State Library of New South Wales

She wrote a suite of Indigenous-themed poems in the 1840s, publishing poems in newspapers such as The Eagle Chief (1843) or Native Poetry/Nung-ngnun (1848). These poems were criticised by anonymous letter writers, questioning her poetic ability, her knowledge and her choice of subject.

Some critics were frankly racist, refusing to accept the human emotions expressed by Dunlop’s Indigenous narrators.

The Sydney Herald had railed against the death sentences of the men responsible for the Myall Creek massacre, and Dunlop condemned the attitude of the paper and its correspondents. She hoped “the time was past, when the public press would lend its countenance to debase the native character, or support an attempt to shade with ridicule”.

Dunlop would publish with one outlet before shifting to another, finding different editors in the volatile colonial press who would support her.

Poetry of protest

Dunlop wrote in a sentimental form of poetry popular at the time, addressing exile, history and memory. She published around 60 poems in Australian newspapers and magazines between 1838 and 1873, but appears to have written nothing more on Indigenous themes after 1850. This popular writing also contributed to poetry of political protest, galvanising readers around causes such as transatlantic anti-slavery.

Read more:

Five protest poets all demonstrators should read

The plight of Indigenous people under British colonialism inspired many writers, including “crying mother” poems that harnessed the universal appeal of motherhood.

Dunlop’s poems The Aboriginal Mother and The Irish Mother are linked to this literary trend, but her experience of colonialism lent her poetry more authority than writers who sourced information about “exotic” cultures from imperial travel writing and voyage accounts.

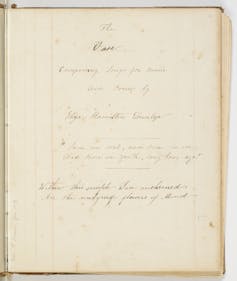

In the early 1870s, Dunlop collated a selection of poetry, The Vase, but she was never able to publish. Family demands and financial constraints precluded it.

State Library of New South Wales, B1541

Dunlop died in 1880. Like many women of the time, her writing was neglected and forgotten, until it was rediscovered by the literary critic and editor Elizabeth Webby in the 1960s.

Webby identified Dunlop as the first Australian poet to transcribe and translate Indigenous songs, and as among the earliest to try to increase white readers’ awareness of Indigenous culture. Webby published the first collection of Dunlop’s poems in 1981.

Today, communities and linguists regularly use Dunlop’s transcripts for language reclamation projects in the Upper Hunter Valley.

Last year, 140 years after Dunlop’s death, Wanarruwa Beginner’s Guide — an introduction to one language of the Hunter River area — was published.

At the launch, language consultant Sharon Edgar-Jones (Wonnarua and Gringai) movingly recited one of the songs Dunlop transcribed: revitalising the words of the Indigenous women and men to whom Dunlop listened, when so few white Australians were listening at all.

Eliza Hamilton Dunlop Writing from the Colonial Frontier, edited by Anna Johnston and Elizabeth Webby, is out now through Sydney University Press.

![]()

Anna Johnston receives funding from the Australian Research Council (FT130100625).

– ref. Hidden women of history: Eliza Hamilton Dunlop — the Irish Australian poet who shone a light on colonial violence – https://theconversation.com/hidden-women-of-history-eliza-hamilton-dunlop-the-irish-australian-poet-who-shone-a-light-on-colonial-violence-161592