Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Alastair Blanshard, Paul Eliadis Chair of Classics and Ancient History, The University of Queensland

The Musicians 1597

Oil on canvas

92.1 x 118.4cm

Rogers Fund, 1952 / 52.81

Collection: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Review: European Masterpieces from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Queensland Art Gallery & Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane.

Thanks to the pandemic, exhibitions such as European Masterpieces from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, which opened at QAGOMA on the weekend, are fraught with logistical difficulties. Quarantine rules and social distancing requirements, not to mention the actual health effects of COVID, have dramatically affected the ability of gallery and museum staff to plan, oversee and shepherd high profile exhibitions into existence.

The fact they are open at all stands as an extraordinary demonstration of trust between institutions and their commitment to the power of masterworks to speak to the human condition.

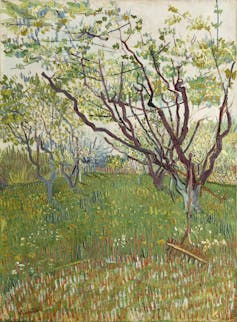

The Netherlands 1853–90

The Flowering Orchard 1888

Oil on canvas

72.4 x 53.3cm

Signed (lower left): Vincent

The Mr and Mrs Henry Ittleson Jr Purchase Fund,

1956 / 56.13

Collection: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The excuse for this exhibition was a major refit of the European Galleries at the Met. Planned long before the pandemic, exhibitions like this one take on new meaning in current times. None of us are going to be able to travel with ease to New York any time soon. These exhibitions remind us of what we are missing. So, as our memories of the joy of visiting international galleries fade, what impression of the Met emerges from this show?

Certainly, the quality and depth of its collection shines through. This exhibition doesn’t give us all the Met’s greatest hits. Everyone will have a favourite painting that didn’t make the cut. However, the curatorial choices are clever.

It is fun to play the mental game of which of an artist’s pictures from the Met you would choose to include. Time and again, it proves to be on the walls in Brisbane.

Lost in the interplay of glances among the figures in Georges de La Tour’s The Fortune Teller, you don’t regret for a moment that we didn’t get his darkly moody The Penitent Magdalen.

France 1593–1653

The Fortune-Teller c.1630s

Oil on canvas

101.9 x 123.5cm

Signed and inscribed (upper right): G. de La Tour Fecit Luneuilla Lothar: [Lunéville Lorraine]

Rogers Fund, 1960 / 60.3

Collection: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Fans of French neoclassical painting are extremely well served by Marie Denise Villers’ portrait of Marie Joséphine Charlotte du Val d’Ognes — a luminous, arresting portrait whose sitter is painted with breathtaking clarity and intensity.

France 1774–1821

Marie Joséphine Charlotte du Val d’Ognes (died 1868) 1801 Oil on canvas

161.3 x 128.6cm

Mr and Mrs Isaac D Fletcher Collection, Bequest of Isaac D Fletcher, 1917 / 17.120.204

Collection: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The exhibition plays up the advantages of distance. Second-tier works gain new life separated from their more famous siblings.

In New York, Poussin’s Saints Peter and John Healing the Lame Man is overshadowed by the riotous profusion of bodies in his Abduction of the Sabine Women. In Queensland, away from the noise of the Sabine painting, it is possible to appreciate the elegant structure of this religious picture.

France 1594–1665

Saints Peter and John Healing the Lame Man 1655 Oil on canvas

125.7 x 165.1cm

Marquand Fund, 1924 / 24.45.2

Collection: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Connoisseurs of technique will not be disappointed by the works on display. Fra Angelico’s The Crucifixion rightly occupies an important place in the history of perspective. One can trace the story of the treatment of light from Caravaggio through to Cézanne.

The Crucifixion c.1420–23 Tempera on wood, gold ground 63.8 x 48.3cm

Maitland F Griggs Collection, Bequest of Maitland F Griggs, 1943 / 43.98.5

Collection: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Venice is expertly evoked with Turner’s characteristically soft, wispy brushstrokes; a perfect contrast to the thickness of paint found in El Greco’s The Adoration of the Shepherds or Rembrandt’s Flora. The Fragonard (The Two Sisters) looks like a Fragonard.

More than this, what makes these works so exciting is the way they brim with ideas. Vermeer’s Allegory of the Catholic Faith is a good example. It’s one of his cleverest paintings. One could spend a week in front of the work unpacking its symbolism and theological ideas.

The Netherlands 1632–75

Allegory of the Catholic Faith c.1670–72

Oil on canvas

114.3 x 88.9cm

The Friedsam Collection, Bequest of Michael Friedsam, 1931 / 32.100.18

Collection: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The works not only reflect ideas, they stage deliberate interventions. Titian’s Venus and Adonis is a case in point. It shows the couple in a passionate embrace, the moment before Adonis is about to head off on the ill-fated hunt that will cost him his life.

The accompanying label describes this work as “re-imagining” Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the Latin epic about mythological transformations. This fails to capture the dynamism of the relationship. This is a painting desperately keen to escape its origins in Ovid’s work. In Ovid, you never forget that Adonis is the product of incest, the offspring of a mother who burned with unnatural desire for her father.

106.7 x 133.4cm

The Jules Bache Collection, 1949 / 49.7.16

Collection: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Read more:

Guide to the classics: Ovid’s Metamorphoses and reading rape

It is a tale so monstrous that Ovid even warns his readers (or at the very least their daughters) not to read it. Ovid makes you feel uneasy about love. His epic is full of rape and violence. This painting rewrites Ovid’s story and invites you to devote yourself to the pleasures of love, even if they have tragic consequences.

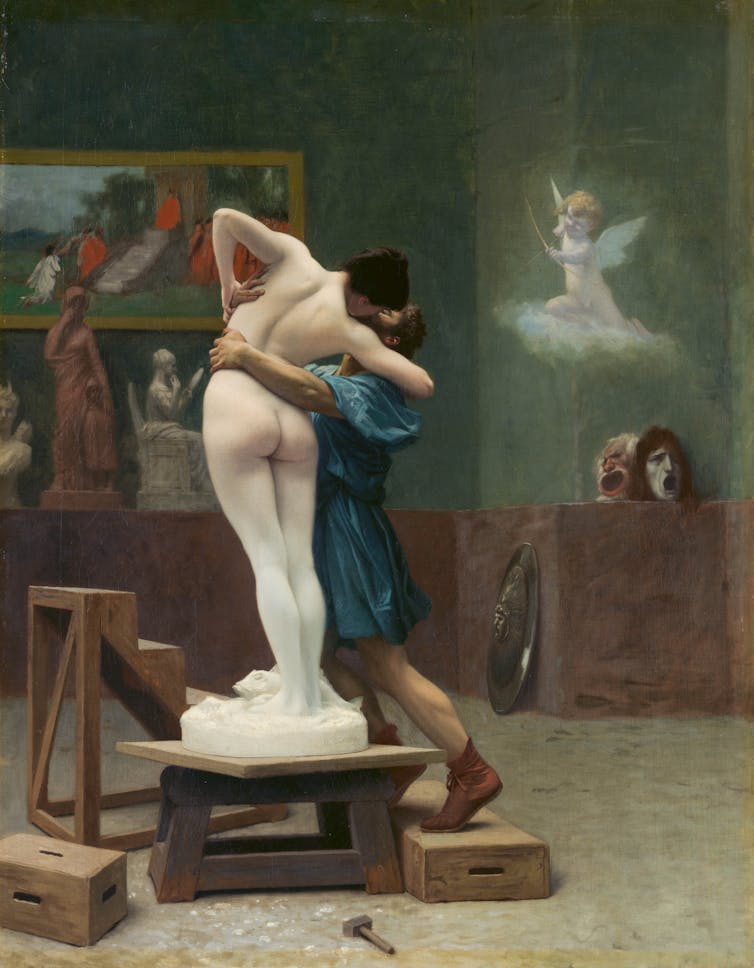

Equally compelling is Jean-Léon Gérôme’s Pygmalion and Galatea. Critics have not been kind to Gérôme. His great crime was to be born so late and live so long. He jumped the wrong way on Impressionism, railing against the “junk” of modern art, and few have forgiven him.

France 1824–1904

Pygmalion and Galatea c.1890

Oil on canvas

88.9 x 68.6cm

Signed (on base of statue): J.L. GEROME.

Gift of Louis C Raegner, 1927 / 27.200

Collection: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Collection: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Yet at the same time, Gérôme was engaged in arguably his most important sequence of works, his series of paintings and sculpture depicting the moment when the fantasies of the sculptor Pygmalion are realised and the statue he has been carving — with whom he has passionately fallen in love — comes to life.

Gérôme’s sequence is uneven. The sculpture is terrible, now perfectly at home in that temple of kitsch, Hearst Castle in California. The reason why that sculpture fails is why this painting succeeds. In the sculpture, despite a bit of added paint, we see only marble.

Here, in an example of virtuoso painting, Gérôme plays with the transition of stone to flesh. We see a miracle unfolding before our eyes. It is a painting inviting us to contemplate art’s ability to imitate, perfect, mediate and complicate our relationship with the world. In this, it is a perfect emblem of this exhibition.

European Masterpieces from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, is showing at QAGOMA Brisbane until October 21.

![]()

Alastair Blanshard does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. European Masterpieces from the Met demonstrates art’s power to speak to the human condition – https://theconversation.com/european-masterpieces-from-the-met-demonstrates-arts-power-to-speak-to-the-human-condition-160462