Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Victor Araneda Jure, Teaching Associate / Filmmaker, Monash University

Unsplash/Joe Ciciarelli, CC BY

Typically, comics are considered a silent medium. But while they don’t come with an aural soundtrack, comics have a unique grammar for sound.

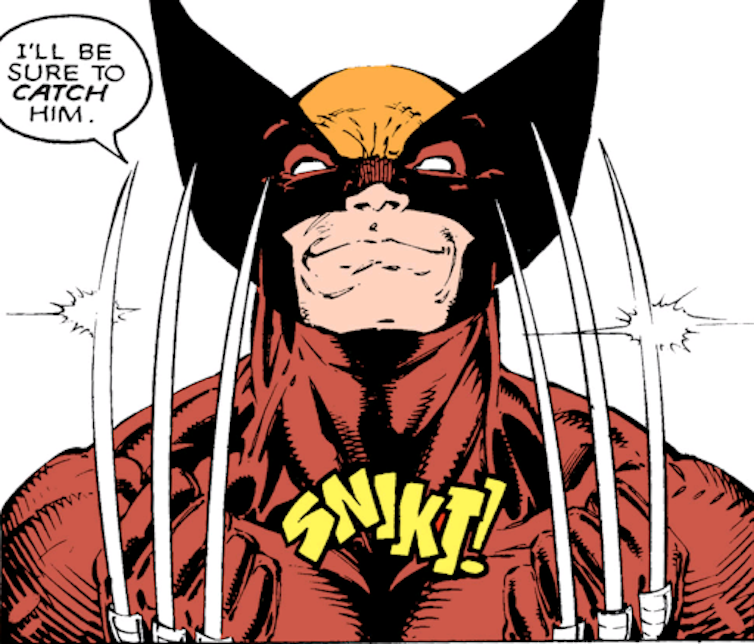

From Wolverine’s SNIKT! when unsheathing his claws, to Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 23 in The Death of Stalin (later made into a film) the use of “textual audio” invites comics readers to hear with their eyes.

Fundamental elements such as symbols, font styles and onomatopoeia (where words imitate sounds) mean reading comics is a cross-sensory experience. New and old examples show the endless potential of the artform.

Unsplash/Miika Laaksonen, CC BY

Holy onomatopoeia Batman!

Onomatopoeia — isn’t unique to comics but comic artists have certainly perfected this figurative form of language. POW! BAM! BANG! appear on the page when Batman and Robin land a punch. BLAM! is the sound made by the Penguin’s umbrella when it shoots from a distance.

The list of sounds represented by onomatopoeia is limitless in terms of creative potential. There are words that mimic sounds directly, such as SPLOSH! (the sound made by an object falling into water) and made-up sounds like that of Wolverine’s adamantium claws (as we will see further below).

The language of comics offers creative freedom to expand the aural lexicon. One online database lists over 2500 comic book sounds with links to comics images in which they’ve been used.

The Comic Book Sound Effect Database

This can also present special challenges for translators. Sounds represented in comics can range from speech sounds (subject to language rules including those governing how syllables can be formed) to human-made non-verbal sounds like sneezes, to sounds made by objects and environments.

Visual context is important too. We only recognise the warning of Wolverine’s violent retribution in SNIKT! when the word is drawn and displayed next to the hairy mutant.

Author provided

Likewise, the word THWIP! by itself may not mean much. But when positioned in context it can imbue a comic page with excitement and adventure.

Imagine a young man dressed in a tight red-and-blue bodysuit diving at high speed from the top of the Empire State building. Suddenly, just before hitting the ground, THWIP! he shoots spider webs from his wrists, using them to swing from building to building. Both readers and the crowd of enthusiastic fans on the page react: “Here comes Spidey!”

The way they say it

Comic creators also use font style and size and different speech bubble shapes and effects to shout, whisper or scream language.

Bold, italics, punctuation, faded or irregular letters are used to emphasise different features of the written words: fear, courage, loudness or quietness.

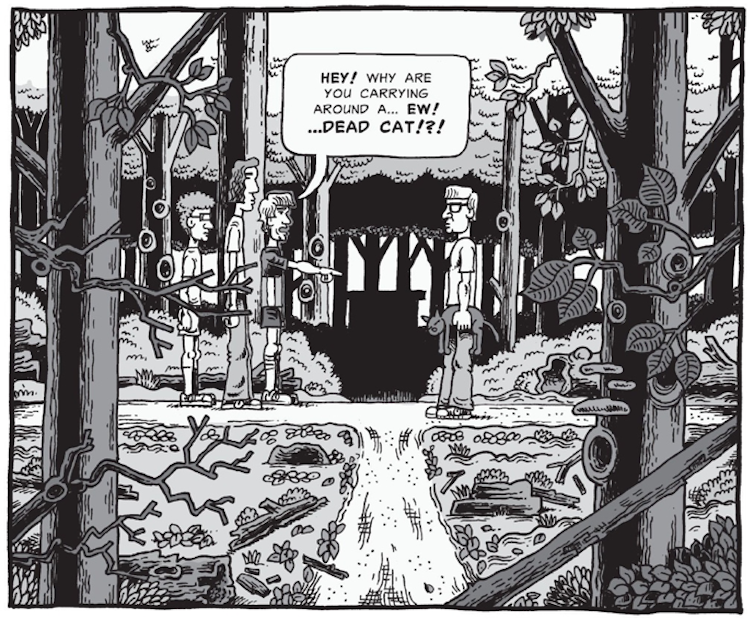

In My Friend Dahmer, created by a school friend of the infamous serial killer, the protagonist is seen carrying a dead cat on his way home by a group of kids. Comics creator John “Derf” Backderf applies bigger-bold words in one of the kids’ speech balloon to emphasise the shouting and surprise of onlookers.

Author provided

Read more:

Heroes, villains … biology: 3 reasons comic books are great science teachers

Music to my eyes

The 1973 manga Barefoot Gen, written by Keiji Nakazawa, explores his firsthand experience of the bombing of Hiroshima and its aftermath.

Gen, the main character, sings through several pages of the story. The author uses a musical note symbol (♪) to indicate where speech bubbles are sung. By the final pages of the fourth volume, Gen sings to celebrate that his hair is beginning to grow again after being affected by radiation poisoning.

When preceded by the easily recognisable musical symbol, it’s virtually impossible to read the dialogue without “hearing” a melody:

♪ “Red roof on a green hilltop …

A bell tower shaped like a pixie hat…

The bell rings, ding-dong-ding …

The baby goats sing along, baa-baa-baa …” ♪

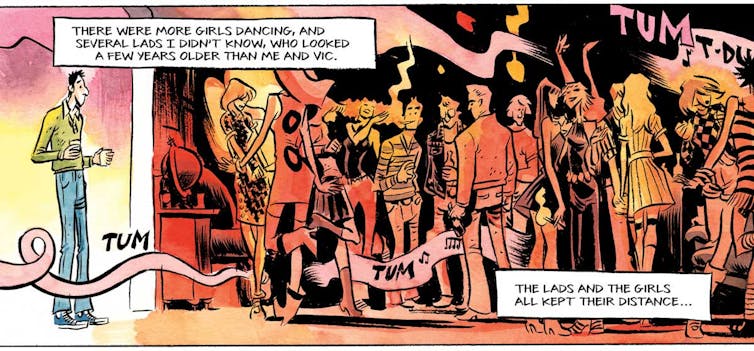

Expanding on this concept, How to Talk to Girls at Parties by Neil Gaiman contains musical panels where the combination of drawings, words and signs present a soundtrack.

Author provided

In film terminology, this is diegetic sound — noises or tunes from within the storyworld — as opposed to a narrative voiceover or a musical soundtrack the characters can’t hear within the story.

In Gaiman’s comic a combination of illustrations, musical notes and words (including the onomatopoeic TUM for a base drum beat) convey the sense that music fills every room of the house where a party is taking place.

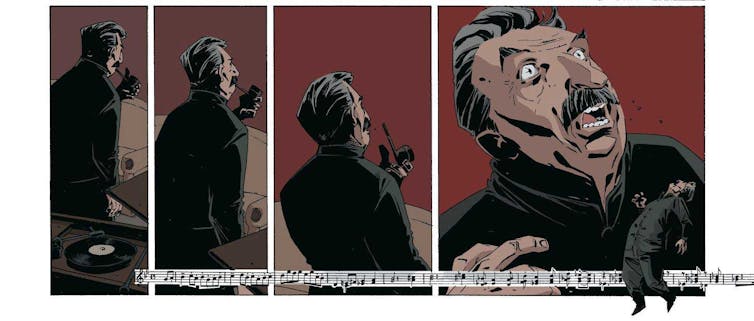

In the political satire comic that inspired a movie, The Death of Stalin creator Fabien Nury and illustrator Thierry Robin show lines from Mozart’s orchestral score for his Piano Concerto No. 23 at the bottom of two pages. This adds drama to a climactic scene where Russian leader suffers a stroke.

Author’

Next time you read a comic book, make sure you listen carefully. KABOOM!

![]()

Victor Araneda Jure does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Kapow! Zap! Splat! How comics make sound on the page – https://theconversation.com/kapow-zap-splat-how-comics-make-sound-on-the-page-160455