Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By John Stone, Senior Lecturer in Transport Planning, The University of Melbourne

As part of efforts to decarbonise urban transport, Australian states and the ACT have announced various zero-emission bus trials and targets for replacing diesel buses. These trials are designed to help resolve some of the complex technical and contractual issues facing bus operators and public transport agencies.

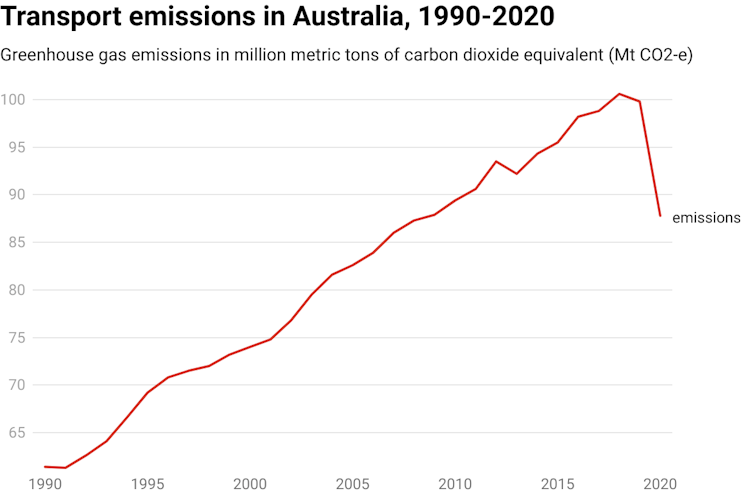

It is important to remember the vital role of buses, and public transport more generally, in decarbonising the transport sector — Australia’s third-largest source of greenhouse gas emissions. We fear this point has been lost in recent climate advocacy highlighting the slow pace of the transition to green propulsion for private cars in Australia.

Chart. The Conversation. Data: National Greenhouse Gas Inventory Quarterly Update December 2020, CC BY

Read more:

Transport is letting Australia down in the race to cut emissions

Our research aims to learn more about the obstacles to an effective transition to zero-emission buses. We are engaging mainly with groups connected with the trial announced by the Victorian Department of Transport in late 2020, but the issues are similar across Australia.

Why can’t we rely on electric cars?

Even if Australia’s transition to green-electric cars is successful, the climate benefits will be less than we need. The carbon costs of manufacturing replacements for Australia’s 20 million-strong vehicle fleet will be equivalent to around 20 years’ emissions from Australia’s dirtiest brown coal generator at Yallourn. And tonnes of concrete and bitumen will continue to be laid for new toll roads and car parks.

A city of electric vehicles will also perpetuate the fatal burdens of car dependence: urban sprawl, inequitable access to the riches of city life, suppression of cycling and walking, and a host of health risks ranging from physical inactivity to air pollution. Even if exhausts were cleaner, recent UK research shows a significant proportion of damaging particulates come from worn tyres and brake linings.

To protect the climate and to make city life safer, fairer and healthier, we need policies that take cars off the roads, regardless of how they are fuelled.

Orderinchaos/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Read more:

Think taxing electric vehicle use is a backward step? Here’s why it’s an important policy advance

Bus services are under-utilised — we can fix that

The technical complexities of the transition to zero-emission buses could, if we are not careful, lead governments to lose sight of this bigger picture. Buses can help reduce demand for car travel, but only if they operate as effective links in a seamless public transport network.

In Melbourne, for example, many buses run almost empty. Routes are convoluted and services infrequent. It would be a travesty to invest millions in moving to greener buses without improving services in ways that increase patronage.

We can use internationally proven techniques to restructure the network so buses provide practical and convenient alternatives to the car. We can then attract a new generation of riders who currently think that “buses are not for me”. This is achievable within current Australian urban densities.

Read more:

Why cities planning to spend billions on light rail should look again at what buses can do

What other challenges must be overcome?

The first technical challenge is to decide between electric battery and hydrogen power. Most governments are leaning towards batteries. This is largely because the technology and its support systems are more evolved.

However, not all battery buses are created equal. One configuration might work well for a bus that will operate on short routes and can easily return to base to recharge. A bus that will operate on longer or steeper routes might need a different set-up. Operators will need to understand these trade-offs before they order new vehicles.

MDRZ/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

As established supply chains and cost structures for fossil fuels become obsolete, operators will also need to come to grips with the intricacies of Australia’s electricity market. At the same time, the power industry is grappling with new forecasts for demand and the infrastructure required for secure supply. Added to this, there are fears of a repeat of the “gold-plating” by private energy providers and distributors that has plagued the industry in recent years.

The change of power source also creates new challenges for fleet managers. If the transition takes several years, how will an operator manage the changing demands on depot space for refuelling and maintenance? Are depots in the right locations for new patterns of refuelling and deployment? How will the workforce gain the new skills they will need?

Issues won’t be resolved overnight

These issues and other technical questions can certainly be resolved. However, the institutional framework in which this must occur makes it hard to imagine it can be done quickly.

In Melbourne, buses operate under more than 15 different contracts, some with multinationals and others with tiny family businesses. These contracts vary in their provisions for determining routes and frequencies, for fleet and depot ownership, and for rollover or re-tendering. This complexity is a historical legacy compounded by decades of political and bureaucratic inertia.

The challenge for governments is to find a path to introducing zero-emission buses and reforming bus networks that deals with the technical uncertainties and the allocation of cost and risk in a fragmented market. The arrival of new commercial players — offering combined bus procurement, operation, charging infrastructure and energy supply — makes the market all the more complex. Nevertheless, success is crucial for the climate and for the health of our cities.

Read more:

Climate policy that relies on a shift to electric cars risks entrenching existing inequities

![]()

John Stone has received funding from the ARC and other Australian and international research bodies and has consulted to state and local governments. He provides volunteer support to the Friends of the Earth Sustainable Cities campaign.

Iain Lawrie and Nat Manawadu do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Don’t forget the need for zero-emission buses in the push for electric cars – https://theconversation.com/dont-forget-the-need-for-zero-emission-buses-in-the-push-for-electric-cars-160933