Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Paige Gleeson, PhD Candidate, University of Tasmania

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains images and names of deceased people.

Every contemporary Australian has likely seen Gwoja Tjungurrayi’s image. Tjungurrayi, a stockman, traditional lawman, and survivor of the brutal 1928 Coniston massacre, is the Warlpiri-Anmatyerr Aboriginal man engraved on our two dollar coin.

Tjungurrayi (whose name is sometimes spelled Gwoya Tjungurrayi, Gwoya Jungarai or Gwoya Djungarai) first rose to unlikely fame not on currency, but on the face of a postage stamp. In 1950 he became the first living Australian — settler or Aboriginal — to be featured on a stamp.

From 1950 to 1966, 99 million stamps featuring Tjungurrayi’s portrait were sold, and he became known to Australia and the world as “One Pound Jimmy”.

Now, fresh research has revealed the 1950 stamp was, in fact, not the first to feature Tjungurrayi. The discovery is the latest twist in a life story told in images.The face of Geelong

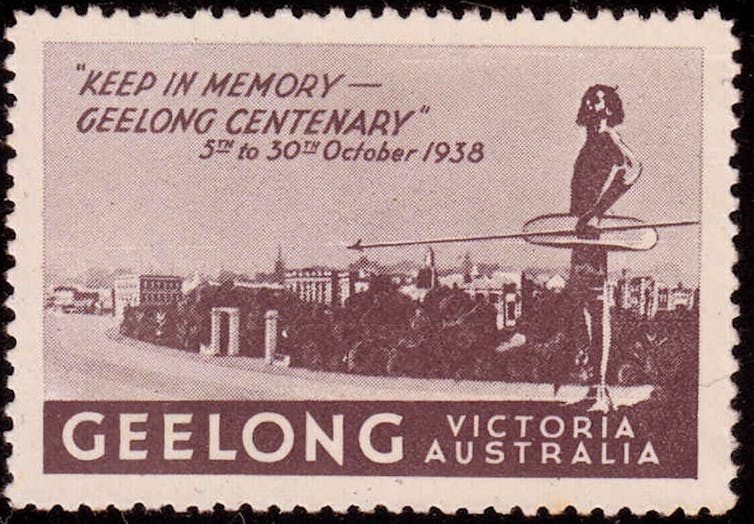

In 1938, a postage stamp was released to mark the centenary of the Victorian town Geelong. It has no decimal mark as it was not issued by the Post-Master General’s Department. Hence it could not be used to send mail but was produced by the city as a collector’s item.

While researching images of Aboriginal people on stamps, in an online stamp collecting forum, I realised the man on the Geelong stamp was unmistakably Tjungurrayi, pictured 12 years before the “One Pound Jimmy” stamp. It’s the first time the image has been formally identified as Tjungurrayi.

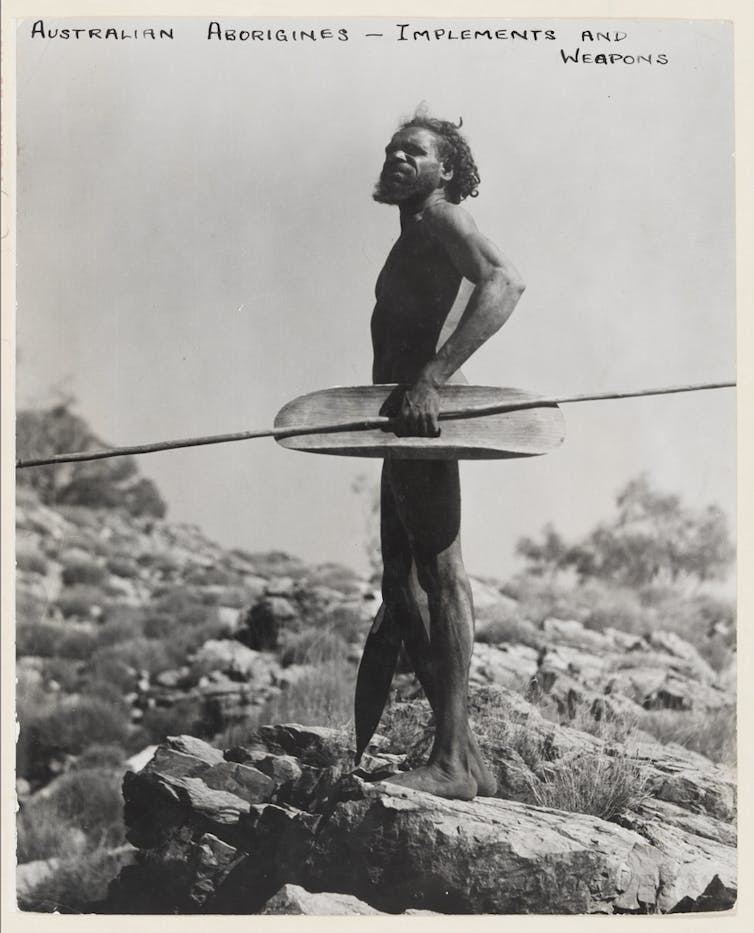

Both stamps are based on a Roy Dunstan photograph of Tjungurrayi that first appeared in the Australian National Travel Association magazine Walkabout in 1936. Tjungurrayi had encountered Dunstan and magazine editor Charles Holmes east of Alice Springs, allowing Dunstan to take his photograph.

This chance encounter had a lasting impact on Tjungurrayi’s life, transforming him into an enduring public figure.

A remarkable life

Tjungurrayi was born around 1895 in the Tanami Desert north-west of Alice Springs. He was a survivor of the 1928 Coniston massacre in which up to 70 people were brutally murdered.

One son described Tjungurrayi “worm[ing] his way out from among the dead and dying”. Another son said he was captured and chained to a tree, but freed himself. He fled to the Arltunga region.

Tjungurrayi was a stockman and station hand by trade. But he was also a traditional lawman, land custodian, cultural intermediary and guide for visiting anthropologists, and family man. He took his responsibility as a father and law custodian very seriously, and was dedicated to ensuring traditional law and knowledge of country was passed down to future generations.

Tjungurrayi died in March 1965, having lived many years in the Tanami region. Obituaries to him appeared in Northern Territory News and on the Centralian Advocate’s front page.

Between Federation in 1901 and the 1930s, Aboriginal people were conspicuously absent in visual representations of Australian nationhood, which centred on native flora and fauna.

The use of Aboriginal motifs on stamps prior to Tjungurrayi’s image in 1950 was rare. The first stamps to feature Aboriginal themes were released between 1934 and 1950 — but there were only four designs and they didn’t portray real people.

Still, the use of images like that of Tjungurrayi exemplify what academic Jillian E. Barnes calls the “pioneer tourist gaze”, presenting him as an adversarial “other”.

Australian modernist artists and writers at this time such as Margaret Preston and the Jindyworobak literary movement became interested in Aboriginal designs and mythology, often appropriating these in their work.

“Aboriginalia” souvenirs and bric-a-brac depicting Aboriginal people according to racial stereotypes were displayed in suburban homes. Aboriginal people’s creative works and performances meanwhile, were still commonly classified as “ethnography”, not art, thus they were not afforded the opportunity to represent themselves and their own culture.

The 1938 stamp shows an apparently “authentic” Aboriginal presence in Australia, but relegates it to a distant and ancient time. In doing so it suggests the contemporary presence of Aboriginal people was anachronistic.

Read more: Friday essay: the politics of Aboriginal kitsch

A new generation

The Geelong centenary stamp may have drawn inspiration from a 1934 Victorian centenary stamp. In both, a standing Indigenous figure is used to contrast the supposed “stasis” of Aboriginal pre-history with the “progress” and modernity of the Australian settler colony.

But as Tjungurrayi’s own life story demonstrates, Aboriginal people continued to survive and thrive, often against the odds. Tjungurrayi’s three sons became leaders in the Western Desert art movement in the 1970s.

One son, Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri, became one of Australia’s best known and well regarded Aboriginal artists.

In 1988, a new chapter in legacy of the family’s engagement with the postage stamp began.

The painting Ancestor Dreaming (1977) by Tjungurrayi’s son Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri was featured on an Australia Post stamp as a part of a series celebrating Western Desert art.

Unlike his father’s designation as “Aborigine” in 1950, or his anonymity on the 1938 stamp, Tim was showcased as a significant artist.

In 2019, the Northern Territory electorate formerly named Stuart was renamed Gwoja in honour of Tjungurrayi.

Contemporary Australia is finally willing and able to remember and celebrate Tjungurrayi as an Elder, lawman and survivor.

Read more: A stamp of approval for legendary sports commentators – but only the male ones

– ref. Elder, lawman, survivor: new stamp discovery is the latest chapter in Gwoja Tjungurrayi’s remarkable life in pictures – https://theconversation.com/elder-lawman-survivor-new-stamp-discovery-is-the-latest-chapter-in-gwoja-tjungurrayis-remarkable-life-in-pictures-161437