Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Duncan Keenan-Jones, Lecturer in Ancient History, The University of Queensland

In the second episode of the current season of the TV show Lego Masters, contestants were asked to build a castle — then watch it be destroyed by a bowling ball.

In the lucky dip that followed, teammates Fleur and Sarah drew a Spartan figure to signal their theme for the task (others worked on Viking, Medieval or samurai strongholds). They went on to build a giant Spartan warrior, standing protectively against white city walls.

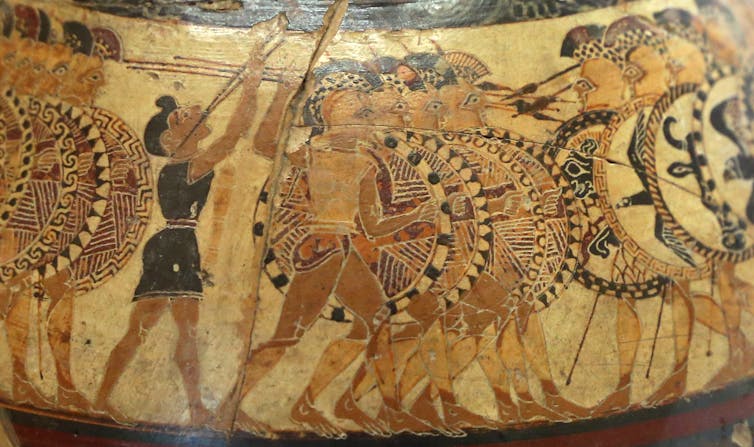

The inclusion of Sparta in a gathering of Lego warrior figurines might seem incongruous to those familiar with ancient history. Sparta, located in Greece’s southern peninsula, the Peloponnese, was one of the oldest and most powerful Greek city-states. Helen, whose abduction started the Trojan War, was married to the king of Sparta in Homer’s Illiad (probably composed in the 8th century BCE).

Read more: Guide to the classics: Homer’s Iliad

Sparta was eventually absorbed into the Roman Empire in the 2nd century BCE. But the Spartans are now a touchstone of popular culture: portrayed in movies such as 300 and Troy, and video games such as Assassins’ Creed: Odyssey and Rome: Total War.

Unfortunately for these hopeful Lego Masters, the city of Sparta was not famous in the ancient world for its walls — but for its lack of them.

Read more: Structuring thought and imagination brick by brick, Lego is more than child’s play

Surrounded by men, not bricks

The Athenian historian Thucydides was probably alluding to this lack of walls when he described the primitive urbanism of Sparta. Later Greek and Roman authors, including the philosopher Plato, considered Sparta’s lack of walls to be a reflection of Sparta’s belief in the superiority of its justly famed soldiers.

As Sparta’s mythical founder Lycurgus is reputed to have said: “A city will be well fortified which is surrounded by brave men and not by bricks.”

Other Spartan notables insulted (in the ancient Greek mindset, at least) cities with impressive walls by describing them as “fine quarters for women”.

Archaeological excavations in 1906–7 confirmed walls were not built around the town until shortly after 184 BCE, long after the height of Sparta’s power during the Persian and Peloponnesian Wars in the 5th century BCE.

Read more: Curious Kids: who were the Spartans?

And yet, while Sparta was protected by an army and not a castle, Sparta and her Peloponnesian allies did seek to shelter behind a set of walls. Not walls around the city of Sparta, but the walls across the Isthmus of Corinth: the narrow strip of land joining the Peloponnese to the rest of Greece.

This was the fall-back position argued for by many Peloponnesians before and after the eventual defeat of Leonidas and his 300 Spartans by the Persians at Thermopylae in 480 BCE.

The Peloponnesians even offered for other city-states to move their families behind the walls.

Looking for weaknesses

This isn’t to say Spartans didn’t recognise the value of a good wall. They saw them as a barrier to other Greek city-states.

The Spartans attempted to convince the Athenians not to rebuild their city wall after it had been torn down by the Persians when they occupied the city after Thermopylae. Once the Persian threat was reduced after Greek victories at Salamis (480), Plataea and Mycale (479), Sparta began to fear the growing power of Athens.

An unfortified Athens would be at the mercy of Sparta’s dominant land army. A fortified Athens, however, could rely on its dominant navy to supply itself by sea and hold out for a long time against a future Spartan siege.

Cannily, Sparta argued Athens should join with them to fund the building of walls around other, less powerful, city-states (who also happened to be less of a threat to Spartan dominance).

Athens delayed their answer to the Spartans, giving themselves time to hastily erect a wall of sufficient height to withstand a siege.

In the 5th century BCE arms race between Greek city-states, Athens wanted their own set of walls to keep pace with other members of the confederacy.

According to Thucydides (an excellent source, even if he treated his speeches and statistics a bit liberally at times), the Spartans eventually became so fearful of Athens’ growing power they fell into the “Thucydides’ trap” — where a dominant power allows its fear of a rising power to result in conflict — resulting in the Peloponnesian War (c. 431–404 BCE).

Read more: Guide to the classics: Thucydides’s History of the Peloponnesian War

Lycurgus, is that you?

Today’s brick-builders on Lego Masters surrounded their Spartan stronghold with protective walls.

Although this isn’t quite how Sparta was built, Fleur and Sarah’s creation of a giant Spartan warrior towering over the fortifications and facing off invaders (or bowling balls) was an inspired choice. Their work echoed the words of famous Spartans including Lycurgus, Agesilaus and Antalcidas: Sparta’s walls were its warriors.

– ref. What were the Spartans like? Note to Lego Masters: they didn’t build city walls – https://theconversation.com/what-were-the-spartans-like-note-to-lego-masters-they-didnt-build-city-walls-159910