Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Maria Nugent, Co-Director, Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Australian National University

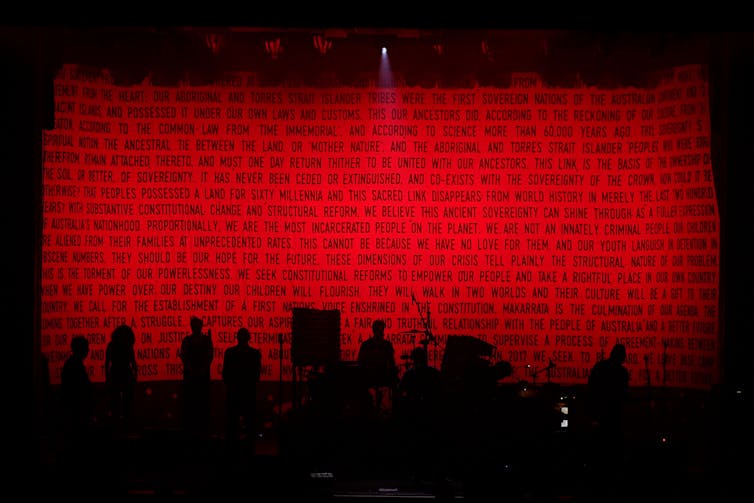

Return to Uluru is the latest book from respected historian Mark McKenna. It is one of a few history books published recently that explicitly engage with the Uluru Statement from the Heart and its demand for a nationwide process of truth telling — one that some key advocates insist should be pursued locally and pluralistically. Not one truth, but many truths.

McKenna has already responded to the Uluru statement in his searching Quarterly Essay, Moment of Truth (2018). Amid that wide-ranging discussion of politics, history and Australian futures, he paused to consider a single street sign in the down-at-heel suburb of Kurnell on Botany Bay’s southern shore, where, in 1770, the Endeavour crew had spent a listless week.

Read more: The Uluru statement is not a vague idea of ‘being heard’ but deliberate structural reform

Through reconstructing a history of a worn out sign announcing Kurnell as the “birthplace of modern Australia”, McKenna traced the changing significance of this site, and the strange politics of foundational myths. This revealing vignette seemed like a chapter-in-the-making, with Kurnell poised to be added to the itinerary of vantage points from which he showed his readers ways to view past, present and future differently.

But it was a tease. McKenna’s next book — this one — turns its back on the coastal fringes and faces inwards, gingerly and then confidently venturing into terrains, actual and abstract, he had not yet traversed.

In Return to Uluru, McKenna continues his journey in search of alternative sites of national foundations — or, national sites of alternative foundations. This quest had begun with Looking for Blackfellas’ Point, subtitled An Australian History of Place, published two decades ago in 2002.

Searching for a satisfying way to intervene in the heat of the history wars, he turned his focus to what had become his own backyard: a bend in the Towamba river in southeastern NSW known in the local vernacular as Blackfellas’ Point, where he had purchased eight acres (3.2 hectares) of land. From there, McKenna’s vista spanned outwards to the far south coast region, reaching backwards to its frontier past and forwards to its racial present.

McKenna then detoured via his magisterial biography of Manning Clark, An Eye for Eternity, a suitable byway for a historian deeply interested in place and the redemptive power of narrative. By the early 2010s, he resumed his Australian journey by essaying four coastal locations. In From the Edge: Australia’s Lost Histories (2016), he explored the peripheral histories of the long stretches of beach of southeast Australia from Gippsland to Sydney; Port Essington on the Cobourg Peninsula in west Arnhem Land; Murujuga in the Pilbara in the northwest and Gangaar (Cooktown) in Far North Queensland.

These off-centre places were offered as viable and lively alternatives to the moribund, foundational myths of single moments of bloodless and benign possession. Such myths are gradually reaching their use by date, although still hanging on as last year’s commemoration of Cook and the Endeavour proved.

Read more: A failure to say hello: how Captain Cook blundered his first impression with Indigenous people

Redemption

And so, Return to Uluru sees McKenna venture inland — for the first time. Heading inwards, he makes use of those stories of discovery and exploration, with which settler Australians (particularly those of a certain age) are familiar, to insert himself into a practised way of encountering the mythologised space of the continent’s heart. The opening section of the book has the quality of re-enactment; it is hard to know how ironic it is. This is a history approached from the outside in.

But the explorer narrative makes sense since it turns out McKenna is a rare creature — someone who had not yet made the pilgrimage to Uluru and the fabled Centre. And so, the “return” in the book’s title is initially a puzzle: Who then, if not the author, is making a return to Uluru? What is returning — or being returned?

It takes the remainder of the book — which is part travelogue, part detective story, part historical narrative and part political treatise — to appreciate in all dimensions this powerful metaphor of return.

With the Centre reached, the second section of the book, called Lawman, focuses on a policeman, Bill McKinnon, who murdered an Aboriginal man, Yokununna, in 1934. McKinnon is reasonably well-known in scholarship on the Northern Territory. His killing of Yokununna, an Anangu man arrested on suspicion of being responsible (along with others) for the death of an Aboriginal stockman, is likewise amply documented since it was the subject of a federal government inquiry. This part of the book provides a narrative retelling of episode — a seamless weaving together of the official story and its obfuscations and competing interests.

Reading this part is a reminder the audience for this book is not the critical historian who is wondering when the debates about policing in the NT or the contradictions of government policy will be canvassed. The archive holds secrets and stories, and this is an “archive story”, which requires little critical commentary.

If the four “off-the-beaten-track” coastal sites of From The Edge were chosen for the ways they lent themselves to the work of revelation — of hidden histories or discarded truths — Uluru provides McKenna scope for the work of redemption.

In this case, redemption comes through the belated admission of a sin that was denied — or covered up — for which the perpetrator avoided punishment, even as he lived out his life knowing that he had dissembled. That is the Uluru to which McKenna returns through his historical scholarship.

As with all his books, the work of historical reckoning that McKenna pursues through the poetic telling of history operates simultaneously at a series of scales: the individual, the family, the local, and the national. It is the same rhetorical move that originally allowed McKenna’s own land on the NSW south coast to become a space of imagining on a national scale. And now, Uluru speaks again to the nation’s unfinished business.

This time it is a single site (a cave near Uluru), a singular episode (a newly-minted territory policeman chasing accused Aboriginal men), and a split second (when the policeman’s bullet kills one of them) that becomes the viewfinder for seeing past, present, future anew.

Ethical questions

Explaining its emphasis on the “micro”, the book begins with an epigram from the Swiss artist and sculptor, Alberto Giacometti: “By doing something a half centimetre high, you are more likely to get a sense of the universe than if you try to do the whole sky”.

But we are left with the question of whether a focus on the microcosmic is a productive model for this urgent and difficult work of national truth telling? Might it be a problem that a string of episodes — but not structures — are revisited and revised?

By the book’s third section, the power of the quest begins again — and here we are not only travelling to the Centre or into the past through the surviving official record. We are also jumping on a plane to Brisbane to meet with policeman McKinnon’s family. Here, we delve into other archives — those boxes of papers and other detritus of one’s life, which in Australia are less likely to be found in attics than in garages or, in Brisbane, in that evocative space known as “under the house”.

At this juncture, as the story spins from past to present, from the official memory to family memory, from public archives to private ones, the ethical stakes seem to grow ever greater.

While McKenna is flicking nonchalantly through McKinnon’s personal papers, he finds treasure — “a copious archive of Australia’s frontier” — including the notebook in which the policeman admits he had fired to hit Yokununna. Meanwhile, a curator in a museum in South Australia is searching records and finding the remains of McKinnon’s victim.

Our archives and collections — both public and private — still contain plenty of damning evidence to hold the past to account. These secret stashes. This murky memory-work.

Archaeologist Denis Byrne has described the “ethos of return”, in which the flow of things and knowledge is reversing, coming home — perhaps to haunt, perhaps to heal. This is another kind of redemption. A powerful section of the book deals with the urgent work of taking Yokununna’s remains home — a process interrupted by COVID-19 and still playing out.

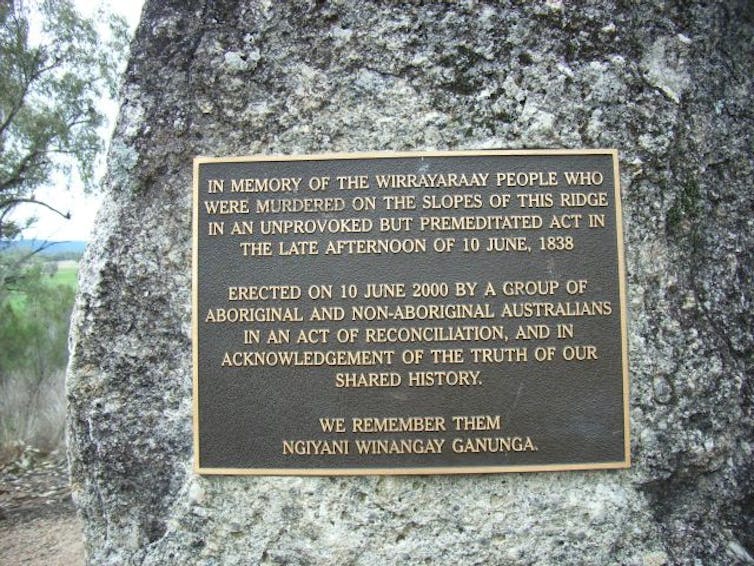

So far, the two families at the heart of this story — McKinnon’s and Yokununna’s — are travelling on parallel journeys; the reckoning will come, as it has powerfully at Myall Creek and other places, when families on opposite sides of a violent past come face to face.

Read more: How can we achieve reconciliation? Myall Creek offers valuable answers

Such a future meeting is not yet guaranteed, but it hangs as a possibility. The Myall Creek memorial was shepherded by local churches and communities. Here, it seems, it will be museum curators and historians who are the nursemaids for re-membering — creating communities around common but differently experienced pasts.

What are we to do?

At the height of the history wars in the 1990s, the anthropologist Gillian Cowlishaw expressed surprise at how readily some Australians were prepared to condemn their own ancestors rather than try to understand them.

She saw this as symptomatic of the polarising tenor of the furore — a failure of collective imagination to apprehend the complexities and contradictions of frontier lives. McKenna’s book (and inquiry) seeks to avoid such simplification and easy distancing from the fraught pasts we inherit.

Read more: Friday essay: it’s time for a new museum dedicated to the fighters of the frontier wars

He nudges his readers to see McKinnon and his crime for what it was: violent, illegal, excessive, irrational, and unconscionable, even if he was exonerated. No-one was found guilty of the killing, although the inquiry’s finding was that the “shooting of Yokununna […] though legally justified, was not warranted”.

McKenna does this not by swift damnation from the comfortable distance of the present, but by paying attention to the chinks in McKinnon’s own conscience. The fact that he held onto a piece of evidence that would expose him even as he spent his long retirement contributing occasionally to myth-making about himself and other police on the NT frontier.

But McKenna also has to deal with the implications for cherished family memories and pride when it becomes clear the generosity and hospitality extended to him by McKinnon’s doting daughter (who is slipping into dementia) is the path to the evidence that exposed her father.

And, indeed, the shadow of memory loss — the cruel play of remembering and forgetting — falls over the whole sorry episode. What happens when the distant frontier takes up residence in the family home? How will we remember our flawed ancestors then?

McKenna shares a story of a difficult meeting with McKinnon’s grandchildren, who understand the gravity of the situation, and articulate their commitment to reconciliation. They are prepared to do what needs to be done to come to terms with their unexpected inheritance; what that will be remains to be seen.

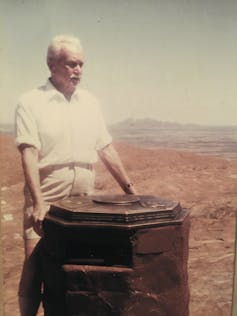

The book ends – surprisingly, jarringly, uncomfortably – with a sympathetic portrait of McKinnon, sitting atop an overturned box playing a violin. The context of the photograph is explained (McKinnon took it and annotated it). But we are left with the question: What do we do with these benign and romantic images of men who murdered and got away with it because the racial structures of Australian society ensured they would?

Is this the challenge of a much anticipated process of truth telling? Not that we will return to the big historical truths that in some ways, we all already know, but that we will have to revise our own and others’ family myths and treasured memories, finding a way to reconcile or hold in tension our love of — and our abhorrence for — the sins of the fathers?

This is the redemptive strain in McKenna’s work — that quest for grace — which perhaps has echoes of his biographical subject Manning Clark and his belief in the moral purpose of the historian’s craft.

Return to Uluru, by Mark McKenna, is published by Black Inc.

– ref. Friday essay: truth telling, Return to Uluru and reckoning with the sins of fathers – https://theconversation.com/friday-essay-truth-telling-return-to-uluru-and-reckoning-with-the-sins-of-fathers-155118