Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Mardi McNeil, Postdoctoral researcher, Queensland University of Technology

Mention the Great Barrier Reef, and most people think of the rich beauty and colour of corals, fish and other sea life that are increasingly threatened by climate change.

But there is another part of the Great Barrier Reef that until recently was largely hidden and under-explored.

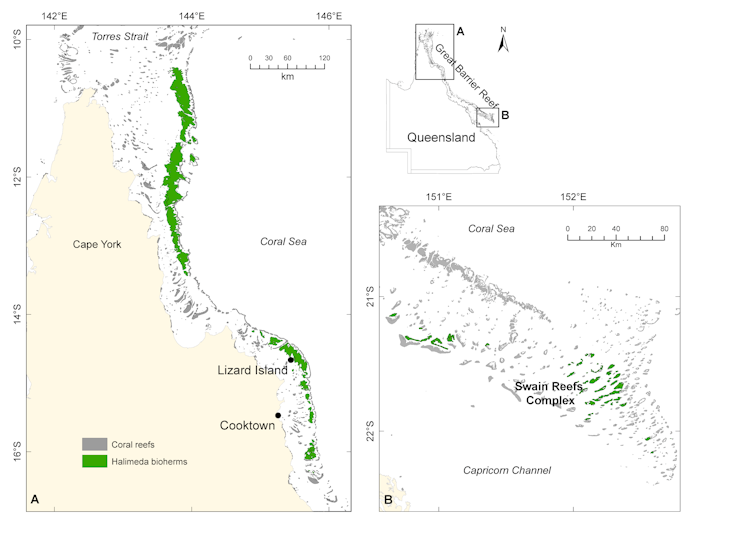

In the northern section of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park there are large Halimeda algal habitats called bioherms (also known as doughnuts because of their shape).

They are constructed by a type of algae (Halimeda) with a limestone skeleton. The tops of the bioherms are carpeted by a living meadow of the algae, yet much of the plant community includes other types of green, red and brown algae and some seagrasses.

Scientists have known for decades of this unusual inter-reef seafloor habitat that lies between the coast and the outer barrier reefs. But they’ve never investigated the diversity of marine life that lives there, until now.

In a new study published today in Nature Ecology and Evolution, scientists examined the community of plants and animals that inhabit these unique areas.

Let’s go deeper

Most studies of tropical marine biodiversity come from shallow coastal and coral reef habitats. We know a great deal about the biodiversity of these parts of the Great Barrier Reef.

But beyond the vision of scuba divers, deeper inter-reef habitats on the shelf, such as the bioherms, have been largely under-explored.

In our study, we used a dataset of all the plants and animals recorded from the bioherms and surrounding seafloor habitats. The data came from the Seabed Biodiversity Project, a large study published back in 2007 of the inter-reef biodiversity in the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area.

What we found was surprising. An exceptional diversity of marine life and a distinct community was found to be living on the bioherms.

A diverse community

The biodiversity of marine life was up to 76% higher on the bioherms than the surrounding inter-reef habitats. Species richness was especially high for plants and invertebrates.

The average number of fish species per site was about the same in both Halimeda and non-Halimeda habitats. In total, 265 species of fish were observed in the bioherms, including sharks and rays.

Overall, more than 1,200 species of animals were recorded from the bioherms. The majority of these (78%) are invertebrates.

A distinct community

The composition of plant and animal communities on the bioherms was also distinctly different to the surrounding inter-reef areas.

Some 40% of bioherm species were unique to that habitat in the study area. The community included many sponges, snails and slugs, crabs and shrimps, brittle stars, sea urchins and sea cucumbers.

The fish community on the bioherms was also distinct from surrounding habitats. The two-spot wrasse, threadfin emperor and black-banded damselfish were particularly common.

Most interesting about the bioherm fish community was the occurrence of some species such as the yellowtail angelfish generally thought to live mostly on coral reefs. Some of these reef-associated fishes have been increasingly observed in a range of non-reef habitats.

These multi-habitat users may be using the bioherms for shelter, feeding, spawning or as nursery grounds. Understanding the connections between shallow coral reefs and deeper bioherms is important to better understand how the reef and inter-reef habitats function.

An unusual habitat

The Halimeda bioherms are arguably the weirdest habitat in the Great Barrier Reef.

Recent high-resolution seafloor mapping using airborne lasers revealed the bioherms form a seafloor that looks like fields of giant doughnuts 20 metres high and 200 metres across.

The tops of the bioherms lie some 25-30 metres below the surface, so can’t be seen from boats passing over.

Deeper water and the remote location has meant the bioherms have been mostly invisible to marine biologists that work on the nearby shallow coral reefs.

Under threat from climate change

We are only just beginning to understand the importance of Halimeda bioherms as a habitat to support biodiversity in the Great Barrier Reef.

But just as the rest of the Great Barrier Reef is likely to be impacted by the effects of climate change, so too are the bioherms.

Potential threats to the bioherms include marine heating, ocean acidification and changes to circulation patterns.

Read more: Under the moonlight: a little light and shade helps larval fish to grow at night

It has been more than 15 years since the inter-reef Seabed Biodiversity Project. The five-yearly Great Barrier Reef Outlook Report says little is known about any ecological trends in the bioherm habitat.

Our new study provides a baseline of the biodiversity of Halimeda bioherms at a single point in time. But questions remain about the present state of this ecosystem and its resilience on short and long-term physical and biological cycles.

Long-term monitoring of these unique and hidden habitats is critical to more fully understand the overall health of the Great Barrier Reef.

– ref. Life on the hidden doughnuts of the Great Barrier Reef is also threatened by climate change – https://theconversation.com/life-on-the-hidden-doughnuts-of-the-great-barrier-reef-is-also-threatened-by-climate-change-154266