Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Brooke Collins-Gearing, Senior Lecturer, University of Newcastle

Review: Firestarter – the Story of Bangarra, directed by Wayne Blair and Nel Minchin

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains names and images of deceased people.

Watching Firestarter is like being immersed in a Knowledge Story. A story that contains deep, secret knowledge at its heart, while sharing an outside, public version. If I had to sum up the outside layer of this story, I would say it is one about energy transformation.

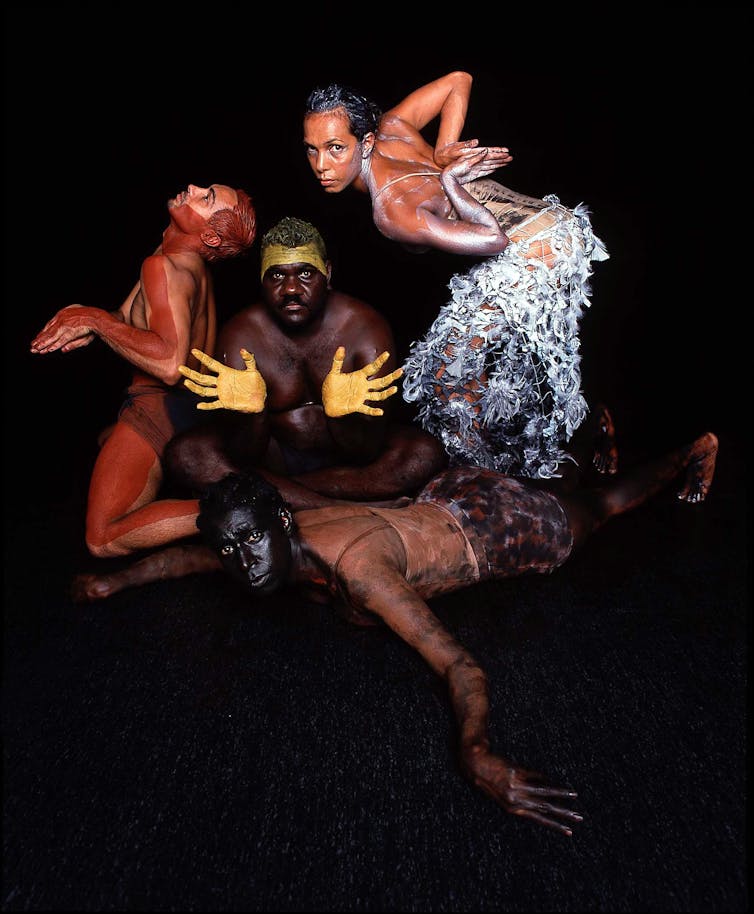

The film gives insight into the emergence of contemporary Indigenous dance in 1970s Australia. It’s a story about embodied activism birthed by founding figures such as Carole Y Johnson and Cheryl Stone through the fusion of contemporary dance forms with ancient living ones.

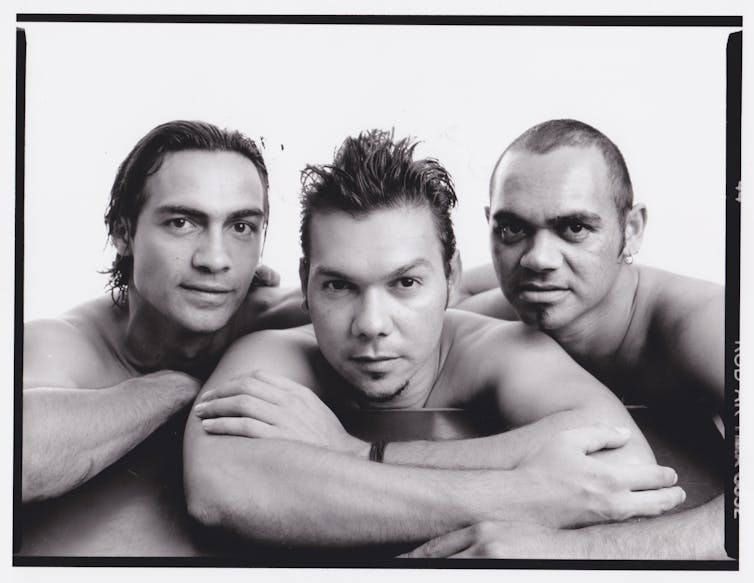

And it’s the story of three Page brothers — choreographer Stephen, composer David and dancer Russell — who established the iconic style that is Bangarra movement.Since 1989, Bangarra Dance Theatre has used dance to craft spaces in important national moments. The opening ceremony of the 2000 Olympics, for example, allowed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge of movement, music and song to be seen, heard and felt.

And just as a public version of a Knowledge Story helps make connections to deeper meanings, Firestarter gives you access to stories containing ancient wisdom fused with contemporary colonial trauma.

Read more: What are message sticks? Senator Lidia Thorpe continues a long and powerful diplomatic tradition

Dreaming to today

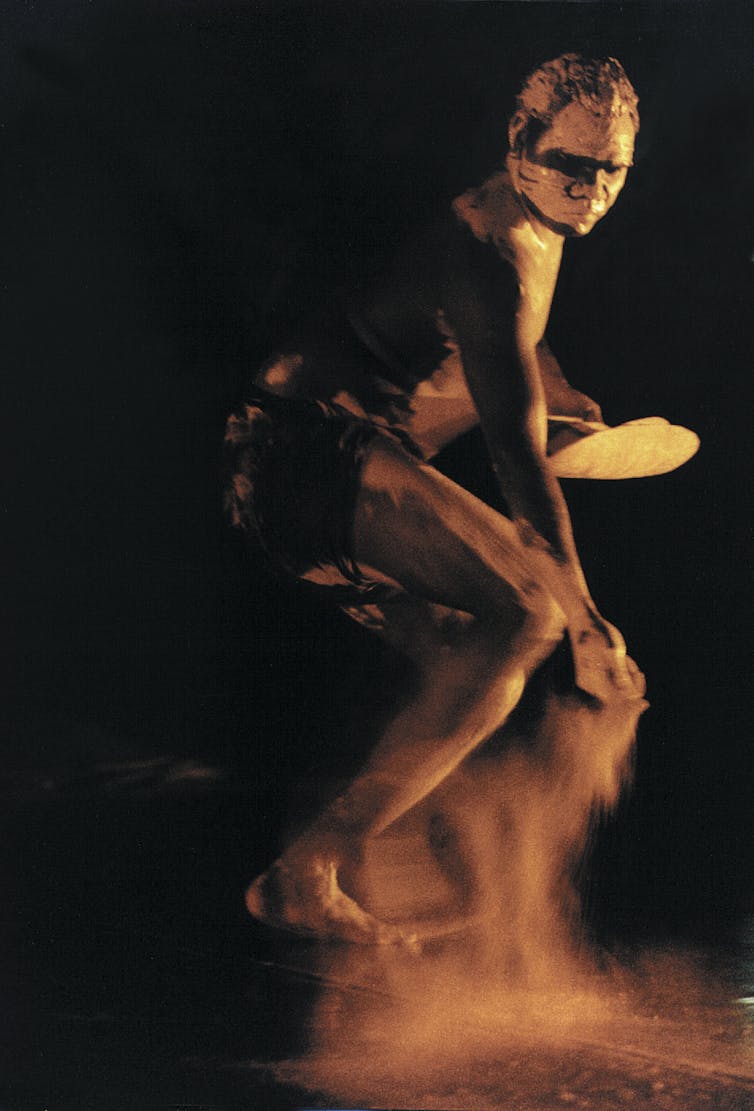

If you’ve ever seen a Bangarra performance you will know that dance is a thread straight to the Dreaming. A ceremonial form with physical and metaphysical knowledge embodied by, and shared with, movement.

Watching the documentary, like watching a Bangarra performance, requires you to pay attention, make connections, explore possible interpretations and potentially be transformed by the telling of it.

The founding of the Aboriginal Islander Dance Theatre in 1975 was a moment in this nation-state’s history that saw the hearts, minds and bodies of mobs of different Blackfellas merge together to begin to shape what would become Australia’s leading Indigenous dance movement.

The dance theatre’s transition into the National Aboriginal and Islander Skills Development Association — better known as Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Dance College — cemented the fusion of cultural knowledges, dance forms, political activism and historical events that would lead to the birth of Bangarra, a Wiradjuri word meaning “to make fire”.

Bangarra has always been both a mirror and a portal. It reflects the aliveness and sentience of stories that come from different mobs and their Countries across Australia while at the same time navigating ongoing colonial trauma.

Through the sharing of stories — the dilemma of how we remember Bennelong, a long history of cultivation through Dark Emu (based on Bruce Pascoe’s book), the yearning for cultural connection in Blak, of the Stolen Generation in Mathinna — the company allows moments of moving through the traumatic to access glimpses of love, healing, transformation and possibilities.

Contemporary Indigenous dance speaks to and of survival, despite 200-odd years of colonial policies aimed at ensuring cultural disconnection.

As the association’s co-founder Carole Y Johnson says in the film:

Australia wasn’t acknowledging Aboriginal people. They had been taken off of their land so many times and I was shocked to understand it was really within living memory of so many people. In terms of dance, Indigenous people were actually ahead and I thought they had something very unique and special to offer.

Read more: Review: Warwick Thornton’s The Beach is a delicate conversation with Country

The cost of the challenge

In telling the story of Bangarra, the film tells stories of creation, trauma, connection and hope.

A significant part of the telling is the influence of the three Page brothers who use music, dance and story to navigate disconnection and reconnection through grief and praise.

Their childhood was lived alongside 12 siblings filled with music, storytelling, laughter and the lived impacts of being cut off from language, land and culture. The brothers went on to use their powerful creative abilities to tell stories about finding your identity, connecting with cultural knowings and acknowledging violent colonial lived experiences.

Such service comes with a heavy responsibility.

The brothers don’t just carry the burden for themselves, but for any Aboriginal and Torres Islander person who knows their ancestors are there but does not know how to access them.

Firestarer explores how the deaths of Russell in 2002 and David in 2016 continues to be felt by artists and audiences, magnified by the power of their performances and music.

Bangarra has, time and time again, stepped up to the challenge of sharing stories through dance to create moments of access for all Australians who hold a relationship with this land’s First Nations’ peoples, its living colonial history and Country itself.

Light in the dark

The story of Bangarra is the story of ignition: Bangarra, for 31 years, has nurtured, protected and breathed life into an ancient ember of light that is then shared with the collective consciousness of Australia — and the world.

Stephen Page, Bangarra’s artistic director since 1991, states:

… art, dance, music, they’re such good medicines. […] Storytelling is the best medicine you can have, it’s what sustains us as a society.

So I need to acknowledge and pay my respect to the heat, oxygen and fuel that is the story of Bangarra and all those who have contributed to creating the energetic and powerful being that it continues to become.

Thank you for carrying the responsibility of telling both living ancient stories woven with painful contemporary ones that speak of both national and personal tragedies.

I recognise your ceremonial medicine.

I am grateful for your light.

Firestarter – The Story of Bangarra is in cinemas now.

– ref. Firestarter — the Story of Bangarra is a film of national and personal tragedies, with light in the dark – https://theconversation.com/firestarter-the-story-of-bangarra-is-a-film-of-national-and-personal-tragedies-with-light-in-the-dark-155114