Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Cecilia Leong-Salobir, Honorary Research Fellow, University of Western Australia

In this series, our writers explore how food shaped Australian history – and who we are today.

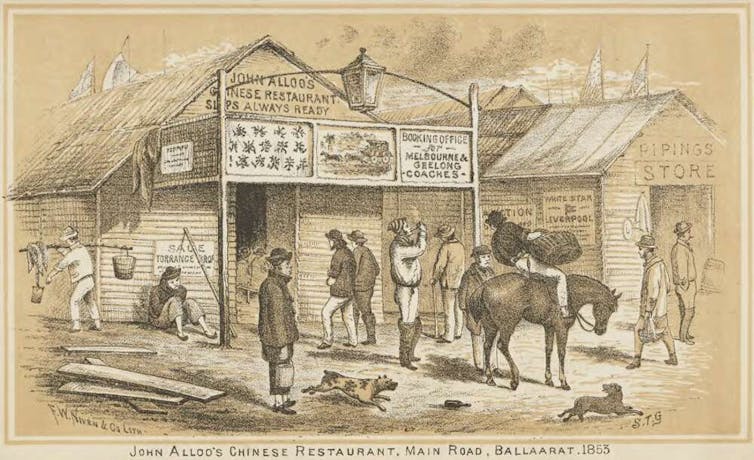

The first whiffs of Chinese cooking in mid-19th century Australia would have emanated from tiny huts owned by Chinese workers in the goldfields. There, they faced racial hostility from the European miners, culminating in the Lambing Flat riots in New South Wales in 1860-61, where Chinese residents of the fields were physically assaulted and had their camps set on fire.

Chinese cooks were also employed in farms and factories and sold food from “cookshops” in the various urban centres for other migrants, such as Sydney’s Chinese furniture factory workers.

Locally sourced meat, seafood and vegetables were complemented by imported ingredients such as Cantonese sausage, tofu, lychee nuts, black fungus and bamboo shoots.

But when it came to the development of Chinese cuisine here, food and politics were deeply entangled. The White Australia Policy of 1901, its amendment in the 1930s and abolition in 1973; the Tiananmen Square protest and other political developments all had consequences for Australia’s Chinese restaurant trade.

From the mines to the cities

When the gold rush years ended, Chinese miners flocked to the cities to start restaurants. The public taste in the first half of 20th century Australia shifted from mutton to lamb, before shifting further. While there were newspaper caricatures of Chinese people eating or selling cats and rats, some Anglo-Australians were soon attracted to flavours other than the one meat and three veg.

Read more: Friday essay: the story of Fook Shing, colonial Victoria’s Chinese detective

Anti-Chinese sentiment and other factors led to the Immigration Restriction Act 1901 – known as the White Australia Policy — restricting migration from Asia and the Pacific.

Most of Australia’s Chinese population before the White Australia policy were from Guangdong and served Cantonese fare. It was this food which took a foothold.

From the early 1900s, Chinese restaurants were concentrated in Chinatowns in Australia, as happened elsewhere around the world. Alongside food, these enclaves provided networks for Chinese labour, trade and provisioning Chinese ingredients.

The Australian public started eating at Chinese restaurants from the 1930s, or brought saucepans from home for takeaway meals. Chicken chow mein, chop suey and sweet and sour pork were the mainstays.

The latter — together with other dishes smothered in sweet sticky sauces — became the lurid-orange epitome of Chinese cuisine for many Anglo Australians.

This fondness was aided and abetted by Chinese cooks who thought this sweetness was what Westerners thought of — and wanted from — Chinese food.

After White Australia

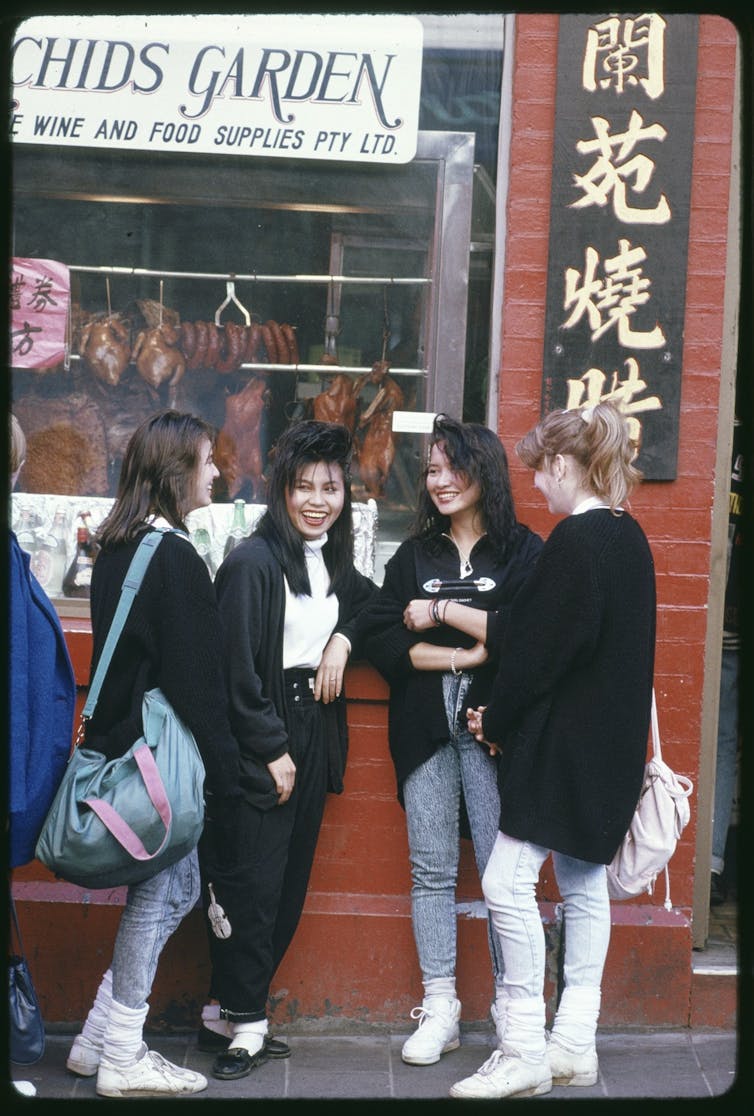

When the White Australia Policy ended, a new wave of more educated and affluent Chinese arrived. Settling in suburbs, they did not require the infrastructure of Chinatown. Later, from the 1980s, international Chinese students took up residence near university campuses.

With this, Chinese restaurants and provision stores were no longer found only in Chinatown. Still, the survival of Chinatowns depends on the Chinese food industry: in restaurants, cafes and grocery shops. The majority of Chinese restaurants in Australia are of the mum-and-dad variety and not part of global fast food conglomerates.

Read more: Sydney’s Chinatown is much more of a modern bridge to Asia than a historic enclave

Both resident and transient Chinese consume and purchase Chinese goods in Chinatown for two reasons: to consume the familiar foods of home or childhood and to reconnect with their culture. And in eating Chinese meals in Chinatown, Australians show off their global palate by tasting a foreign and yet familiar cuisine.

Tiananmen and Hong Kong

Following the 1989 Tiananmen Square student protest, the Australian government granted permanent residence to 20,000 Chinese international students.

They brought food practices from many different regions of China. Importing their own particular ingredients and cooking methods, restaurants started offering cuisines from Hunan, Sichuan, Beijing and Shanghai.

In the years before and after Britain returned Hong Kong to China in 1997, numerous Cantonese chefs migrated to Australia. Locals at the time boasted that the best Hong Kong Cantonese food in the world was found in Perth’s Northbridge.

Today the discerning restaurant diner in Australia looks more for regional foods from China: the hot chilli lamb and noodles from Uyghur cuisine, the delicate dumplings of Shanghai, the Beijing hot pot. “Chinese food” is no longer a good enough descriptor for the variety of cuisines available in Australia.

But while Australians can now eat Peking duck and xiao long bao (soup dumplings), the ubiquitous Chinese restaurant — with its sweet and sour pork and chow mein — still exists across Australia in a culinary time warp. It is evidence of the enduring love for Chinese food here.

The COVID-19 pandemic means this week’s Lunar New Year will be different. Usually marked by an obligatory reunion dinner, this year not every family member will be at the dining table — but every dining table is sure to be piled high with food.

– ref. From lurid orange sauces to refined, regional flavours: how politics helped shape Chinese food in Australia – https://theconversation.com/from-lurid-orange-sauces-to-refined-regional-flavours-how-politics-helped-shape-chinese-food-in-australia-150283