Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Anna Clark, Australian Research Council Future Fellow in Public History, University of Technology Sydney

Summer’s here again. After months of lockdowns, travel bans and uncertainty, that first crunch of warm sand between the toes brings a sigh of relief that, all being well, lasts at least until the end of January. Walking by the waves finally feels like a bookend to what’s been a testing year.

If you’re like me, days at the beach mean watching the tides, walking the clifftops and poking in the dunes. I love shimmying my feet in the wet sand to catch a feed of pipis and gather bait for a sunset fish. Kids jump in the waves and down the embankments, filling their hair with sand and dry seaweed.

It’s a much-needed salve. But a closer examination of the Australian beach reveals this place isn’t simply a retreat from modern life or a hard year’s work. Many thousands of generations have come here before us to savour this place and enjoy its bounty.

Read more: Plenty of fish in the sea? Not necessarily, as history shows

Ancient middens in the dunes exposed by the wind reach back into an archaeological deep time. They’re a granular archive of Aboriginal life which, as the Wirudjuri scholar Michelle Bovill explains:

embodies layers of shells, bones, charcoal and tools, capturing moments in time, celebrations and ceremonies of our ancestors.

In Weipa, Queensland, the middens are so extensive – up to 16 metres high – that they’re visible on Google Earth. Meanwhile, Indigenous oral histories give accounts of the inundation of Naarm (Port Phillip Bay) and the north Queensland coast, which provided the seabed for what’s now the Great Barrier Reef. These histories reveal a knowledge of the beach that seems almost incomprehensible from a settler-colonial perspective.

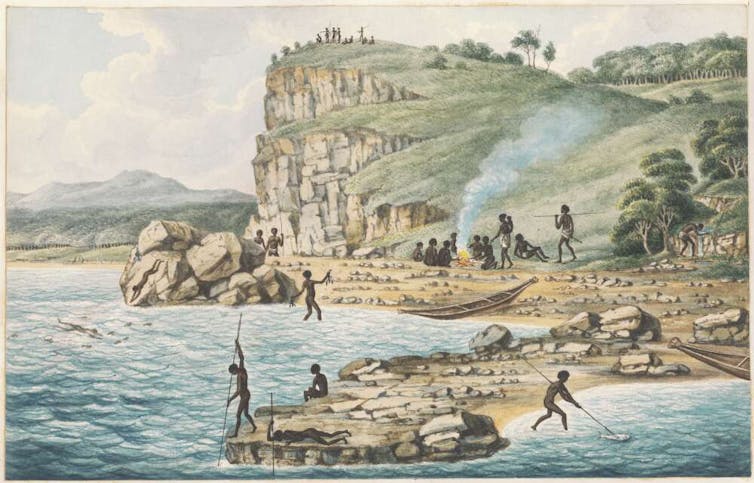

Early colonial accounts from Sydney Cove also show the essential place of the beach for Indigenous communities, as well as its extraordinary natural bounty: water just off Bondi filled with crayfish, giant schools of Australian salmon that seasonally swam into the harbour, and bays filled with native oysters and shellfish. Sydney placenames (such as Cockle Bay, Chowder Bay and Kirribilli – which is believed to mean “good fishing spot”) are like little threads that link us back in time to the environmental history of the city.

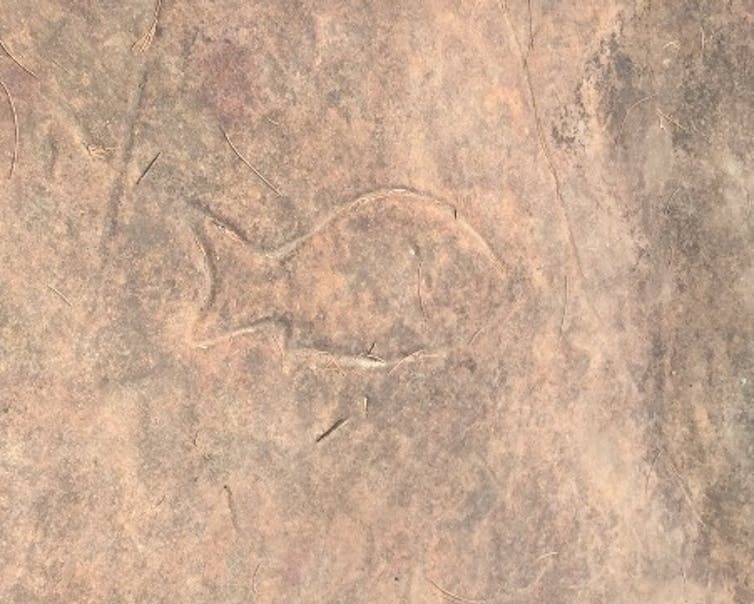

Other Aboriginal imprints remind us the beach wasn’t simply a place for gathering food, but also of contemplation and stories. Vast galleries of rock art right across Australia reveal Indigenous cosmologies that connect land, sea and sky. Giant engravings of whales, sharks, stingrays and fish on sandstone rock platforms around Sydney show how the things that enchant us about the beach today — the natural wonder, the nostalgia of places we played in as children – have been wondrous for millennia.

Even when the beach has been visited by necessity, its allure has been profound. During the Great Depression in the 1930s, unemployed families camped out by the beach right around the country. While many of their old shacks have been removed, some can still be seen at Crater Cove in Sydney and further south at Royal National Park.

The inhabitants of these shanty communities had been driven there by need, to catch and barter fish while they were out of work. But residents also remembered this time in terms of the deep connections to the coastline that sustained them.

Many migrants also describe the importance of beachside activities such as fishing and camping to their growing sense of belonging. Australia’s population swelled by over 1 million arrivals between 1945 and 1955. And, like their Australian-born neighbours, many of those who migrated here from Europe and later Asia found themselves at beach camps on their weekends and summer holidays.

However, not all seaside histories are based on forging connections. Place names like Lime Kiln Bay in Sydney or Limeburners Lagoon in Geelong point to a history of cultural destruction on the beach. Aboriginal middens were dug up and burnt to make lime for the mortar that built colonial cities like Melbourne and Sydney.

Likewise, what can be seen as ground-breaking environmental protections from the late 19th century also confirmed the dispossession of Aboriginal people from Country they had managed and occupied prior to colonisation. The declaration of the Royal National Park just south of Sydney in 1879 was only the second in the world. It reflected the idea that Australia’s beaches and bushland were important enough to be protected and enjoyed, rather than simply a resource to be exploited.

It’s no accident this burgeoning popular and government interest in the Australian landscape coincided with the end of frontier wars. Surviving Indigenous communities had mostly been moved off their country and onto missions, reserves and stations by the turn of the 20th century, allowing “the beach” to become synonymous with Australia’s settler-colonial identity.

The 2005 Cronulla race riots also confirm how that identity has worked exclusively at times — this shared, multicultural place can be the front line for social dislocation and unrest.

Read more: Friday essay: a response to the Cronulla riots, ten years on

Such histories demonstrate communal places like the beach can segregate as well as bring together, as the Goenpul scholar Aileen Moreton-Robinson contends. Swimming and fishing on the beach can be regenerative, connected and grounding, an embodied history that’s passed down through families in place. But the historical terrain of the beach can also be felt unevenly.

That little patch of summer coastal paradise is undoubtedly restorative. But its complex and multilayered history is important to remember, even as we dash over the hot sand for a dip in its glorious cool waters.

– ref. Sun, sand and survival: a short history of the beach in Australia – https://theconversation.com/sun-sand-and-survival-a-short-history-of-the-beach-in-australia-148527