Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By David Peetz, Professor of Employment Relations, Centre for Work, Organisation and Wellbeing, Griffith University

The federal government’s industrial relations “reform” bill offers a new definition of “casual” employment that creates more problems than it solves.

It effectively defines a casual job as anything described that way by the employer at the time a job commences, so long as the employer initially makes “no firm advance commitment to continuing and indefinite work”.

Anyone defined as such loses any entitlement to leave they might otherwise have got through two recent Federal Court decisions.

Fair enough, you might think. Casual jobs are meant to be flexible. There can’t be an ongoing commitment.

But that’s not what the data on “casual employment” tell us.I’ve drilled into previously unpublished data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics to get a better sense of what “casual employment” means for those employed as such.

Overall, what I’ve found suggests the “casual” employment relationship is not about doing work for which employers need flexibility. It’s not about workers doing things that need doing at varying times for short periods.

The flexibility is really in employers’ ability to hire and fire, thereby increasing their power. For many casual employees there’s no real flexibility, only permanent insecurity.

The federal government’s new bill will not solve this. It will reinforce it.

Read more: So much for consensus: Morrison government’s industrial relations bill is a business wish list

Casual definitions

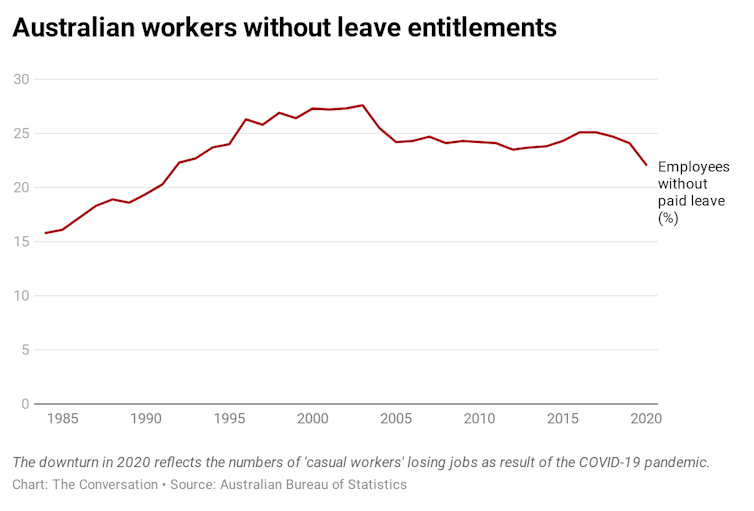

Technically the ABS does not routinely estimate the numbers of casual employees. For a few years (to 2013) it published data on workers who received a casual loading, and it occasionally asks people to self-identify whether they are casuals. But mostly its data on “workers without leave entitlements” (collected quarterly) is used as a proxy measure of casual employment.

About 24% of Australian employees were in this boat in 2019 – a high proportion compared with most other industrialised countries.

Theory versus reality

The ABS data I’ve analysed includes statistics collected before 2012. But since the proportion of employees without leave entitlements has been relatively stable since the mid-1990s, the results remain relevant. They show:

-

about 33% of “casuals” worked full-time hours

-

about 53% had the same working hours from week to week, and were not on standby

-

about 56% could not choose the days on which they worked

-

almost 60% had been with their employer for more than a year

-

about 80% expected to be with the same employer in a year’s time.

Very few (6% of “casuals”) work varying hours or are on standby, have been with their employer for a short time, and expect to be there for a short time.

There are many reasons to question whether an employee without leave entitlements could really be defined as a genuinely flexible casual worker. It’s better to just call them “leave-deprived” employees.

Read more: Self-employment and casual work aren’t increasing but so many jobs are insecure – what’s going on?

A common feature: powerlessness

The common features of all leave-deprived employees are permanent insecurity and low power.

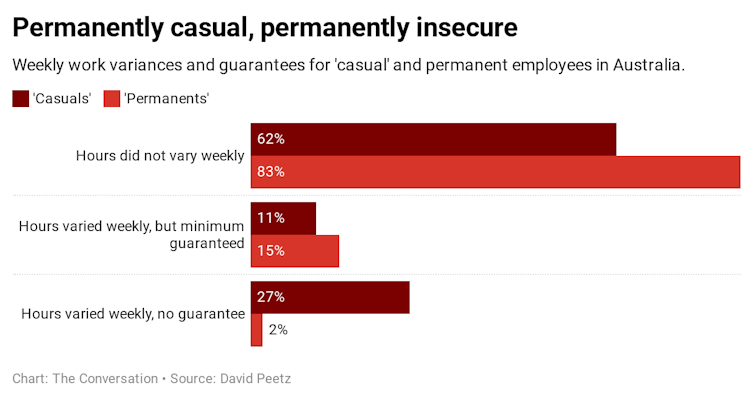

Leave-deprived employees are about twice as likely as “permanent” workers (with leave entitlements) to have variable hours. But almost all “permanent” workers with variable hours have a guaranteed number of minimum hours. Yet less than a third of leave-deprived employees have that guarantee.

Overall, 27% of leave-deprived employees have variable hours and no minimum guarantee of hours. That is the case for only 2% of “permanent” workers (see chart).

We can think of variable hours as reflecting employers’ flexibility needs, and a guarantee of minimum hours as reflecting employees’ power. The big difference between leave-deprived employees and “permanents” is in the power employees have.

Sometimes you hear the term “permanent casuals”. They should more accurately be called “permanently insecure”.

Casual loading

Another sign of low power is how few leave-deprived workers receive the casual loading – the 25% extra pay meant to compensate them for their lack of leave entitlements.

When the ABS used to ask about casual loading, less than half of leave-deprived workers said they got it. That’s hardly surprising, given how often breaches of awards have been uncovered.

A study published in 2019 found low-paid leave-deprived workers in Australia, on average, were paid less than equivalent “permanent” employees.

Low power is what should be expected when an employment contract only lasts as long as the current shift. A worker might not even get formally terminated, just not be given any more hours.

Why have casual employment?

There may be good reasons to have casual employment when work is genuinely intermittent and uncertain.

But that’s not the case for most leave-deprived jobs. They are, instead, long-term and stable – yet still insecure for the employee. The only flexibility in them lies with the employer’s power to withhold work.

Allowing employers to overrule previous court decisions and define who is and is not a casual, as proposed in the current bill, will not overcome any of these problems.

Instead, it will just entrench the practice of employers using “casual employment” to increase their power.

– ref. The truth about much ‘casual’ work: it’s really about permanent insecurity – https://theconversation.com/the-truth-about-much-casual-work-its-really-about-permanent-insecurity-151687