Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Bernadette McCabe, Professor and Principal Scientist, University of Southern Queensland

Biomethane technology is no longer on the backburner in Australia after an announcement this week that gas from Sydney’s Malabar wastewater plant will be used to power up to 24,000 homes.

Biomethane, also known as renewable natural gas, is produced when bacteria break down organic material such as human waste.

The demonstration project is the first of its kind in Australia. But many may soon follow: New South Wales’ gas pipelines are reportedly close to more than 30,000 terajoules (TJs) of potential biogas, enough to supply 1.4 million homes.

Critics say the project will do little to dent Australia’s greenhouse emissions. But if deployed at scale, gas captured from wastewater can help decarbonise our gas grid and bolster energy supplies. The trial represents the chance to demonstrate an internationally proven technology on Australian soil.

What’s the project all about?

Biomethane is a clean form of biogas. Biogas is about 60% methane and 40% carbon dioxide (CO₂) and other contaminants. Turning biogas into biomethane requires technology that scrubs out the contaminants – a process called upgrading.The resulting biomethane is 98% methane. While methane produces CO₂ when burned at the point of use, biomethane is considered “zero emissions” – it does not add to greenhouse gas emissions. This is because:

-

it captures methane produced from anaerobic digestion, in which microorganisms break down organic material. This methane would otherwise have been released to the atmosphere

-

it is used in place of fossil fuels, displacing those CO₂ emissions.

Biomethane can also produce negative emissions if the CO₂ produced from upgrading it is used in other processes, such as industry and manufacturing.

Biomethane is indistinguishable from natural gas, so can be used in existing gas infrastructure.

Read more: Biogas: smells like a solution to our energy and waste problems

The Malabar project, in southeast Sydney, is a joint venture between gas infrastructure giant Jemena and utility company Sydney Water. The A$13.8 million trial is partly funded by the federal government’s Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA).

Sydney Water, which runs the Malabar wastewater plant, will install gas-purifying equipment at the site. Biogas produced from sewage sludge will be cleaned and upgraded – removing contaminants such as CO₂ – then injected into Jemena’s gas pipelines.

Sydney Water will initially supply 95TJ of biomethane a year from early 2022, equivalent to the gas demand of about 13,300 homes. Production is expected to scale up to 200TJ a year.

Biomethane: the benefits and challenges for Australia

A report by the International Energy Agency earlier this year said biogas and biomethane could cover 20% of global natural gas demand while reducing greenhouse emissions.

As well as creating zero-emissions energy from wastewater, biomethane can be produced from waste created by agriculture and food production, and from methane released at landfill sites.

The industry is a potential economic opportunity for regional areas, and would generate skilled jobs in planning, engineering, operating and maintenance of biogas and biomethane plants.

Methane emitted from organic waste at facilities such as Malabar is 28 times more potent than CO₂. So using it to replace fossil-fuel natural gas is a win for the environment.

Read more: Emissions of methane – a greenhouse gas far more potent than carbon dioxide – are rising dangerously

It’s also a win for Jemena, and all energy users. Many of Jemena’s gas customers, such as the City of Sydney, want to decarbonise their existing energy supplies. Some say they will stop using gas if renewable alternatives are not found. Jemena calculates losing these customers would lose it A$2.1 million each year by 2050, and ultimately, lead to higher costs for remaining customers.

The challenge for Australia will be the large scale roll out of biomethane. Historically, this phase has been a costly exercise for renewable technologies entering the market.

The global picture

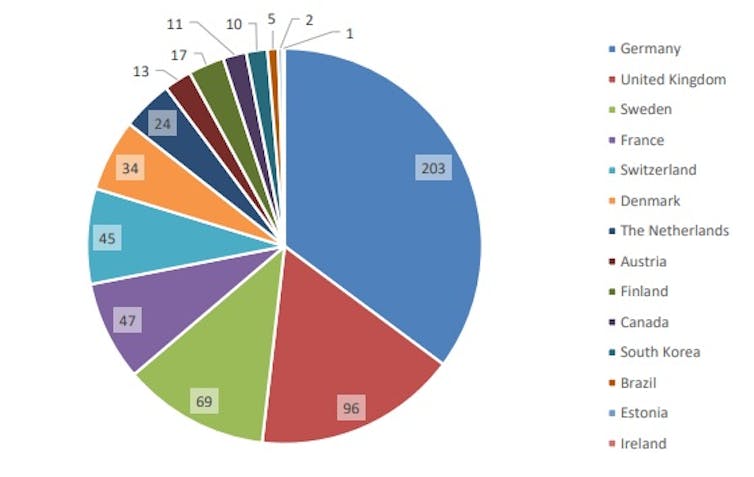

Worldwide, the top biomethane-producers include Germany, the United Kingdom, Sweden, France and the United States.

The international market for biomethane is growing. Global clean energy policies, such as the European Green Deal, will help create extra demand for biomethane. The largest opportunities lie in the Asia-Pacific region, where natural gas consumption and imports have grown rapidly in recent years.

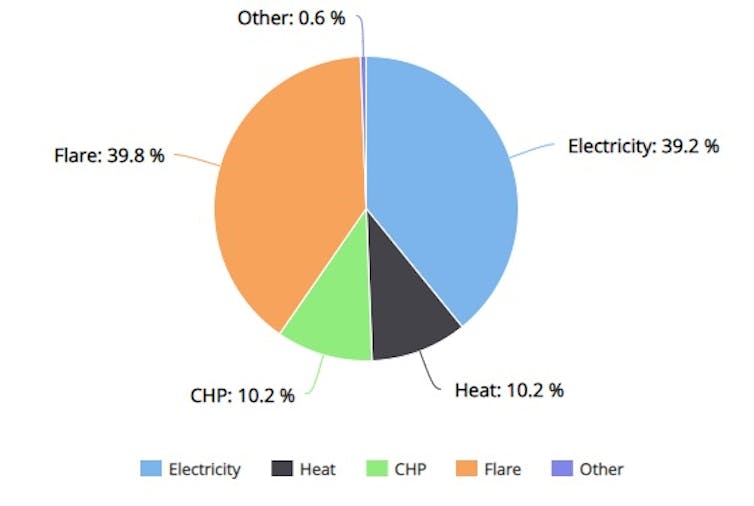

Australia is lagging behind the rest of the world on biomethane use. But more broadly, it does have a biogas sector, comprising than 240 plants associated with landfill gas power units and wastewater treatment.

In Australia, biogas is already used to produce electricity and heat. The step to grid injection is sensible, given the logistics of injecting biomethane into existing gas infrastructure works well overseas. But the industry needs government support.

Last year, a landmark report into biogas opportunities for Australia put potential production at 103 terawatt hours. This is equivalent to almost 9% of Australia’s total energy consumption, and comparable to current biogas production in Germany.

A clean way to a gas-led recovery

While the scale of the Malabar project will only reduce emissions in a small way initially, the trial will bring renewable gas into the Australia’s renewable energy family. Industry group Bioenergy Australia is now working to ensure gas standards and specifications are understood, to safeguard its smooth and safe introduction into the energy mix.

The Morrison government has been spruiking a gas-led recovery from the COVID-19 recession, which it says would make energy more affordable for families and businesses and support jobs. Using greenhouse gases produced by wastewater in Australia’s biggest city is an important – and green – first step.

– ref. Not just hot air: turning Sydney’s wastewater into green gas could be a climate boon – https://theconversation.com/not-just-hot-air-turning-sydneys-wastewater-into-green-gas-could-be-a-climate-boon-150672