Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Melissa A. Wheeler, Senior Lecturer, Department of Management and Marketing, Swinburne University of Technology

The COVID-19 pandemic is changing Australians’ view of public education, our analysis of Australian Leadership Index (ALI) data shows. In contrast to the government’s instrumental view of education, with its focus on producing “job-ready graduates”, the public now takes a wider view of education as a public good.

Public education, such as public schools and universities, is understood as serving the interests of the many, not the few. And the importance of ethics and accountability has only become more pronounced throughout the pandemic.

Read more: 3 flaws in Job-Ready Graduates package will add to the turmoil in Australian higher education

The Australian Leadership Index has tracked public perceptions of leadership across a number of sectors, including public education, since 2018. We analysed ALI scores for public education through three periods – before COVID, first wave and second wave.

An intensifying debate about education

Since the pandemic began, debate about the role of education and its contribution to the public good has intensified. Universities have been at the centre of this debate.Between January and March, before COVID-19 hit our shores, universities were in the public spotlight due to their reliance on international student fees.

In this period, the ALI score (our indexed measure of leadership) for public education dipped into the negative (-2) for the first time since we began tracking in September 2018.

During the first wave of COVID-19 (March-June), public discourse focused on the role of universities in finding a vaccine. At the same time, the exclusion of universities from the JobKeeper program forced them into cost-cutting, with implications for research output. More recently, news of wage theft in universities hit the headlines.

Read more: As universities face losing 1 in 10 staff, COVID-driven cuts create 4 key risks

Despite these challenges, the ALI score for education recovered strongly. It hit a peak (+19) in the June quarter and stabilised in the September quarter (+15).

Education and the public good

Over the past few months, the federal government has brought in sweeping changes intended to encourage students to study science, technology, engineering and mathematics. The stated aim is to produce “job-ready graduates” to fuel economic recovery.

By contrast, our data show the Australian public takes a wider view of education.

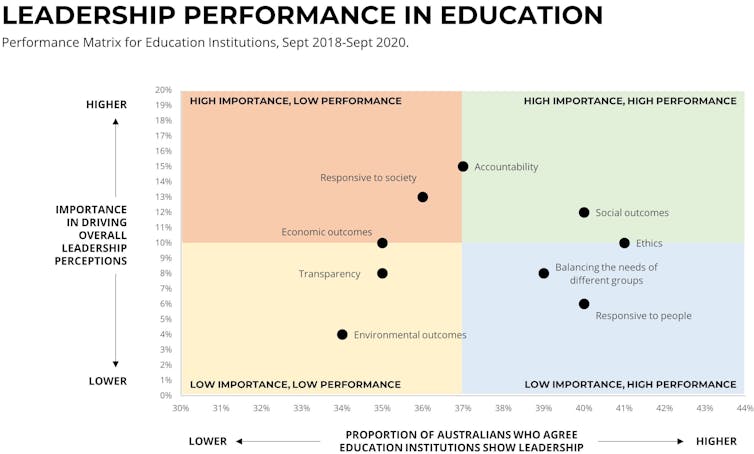

Drawing on nationally representative surveys from September 2018 to September 2020, we statistically modelled how nine different factors have influenced public perceptions of leadership in education institutions.

We then plotted the importance of each factor (vertical axis) against the proportion of Australians who agree education is performing well on that factor (horizontal axis). The results show which factors are important in driving perceptions of education leadership, and also how the sector performs against them.

Notably, Australians see accountability, ethicality and creating social value as highly important for education institutions. The sector performs well against these factors.

By contrast, responsiveness to the needs of society and creating economic value are also important, but the sector underperforms against these factors.

In short, Australians believe that how public education creates value – through demonstrable commitments to ethics and accountability – is as important as the type of value it creates. This reflects an understanding that serving the public interest is as much about process as it is about outcome.

Overall, these results suggests a marked discrepancy between how the government and Australians view public education.

How views changed through the pandemic

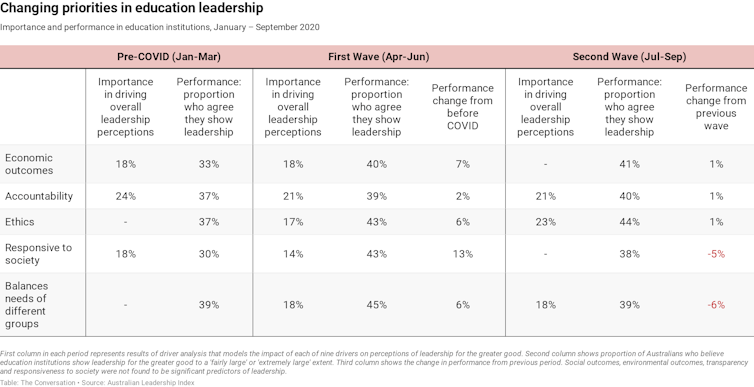

Our data (click on the table to enlarge it) show how Australians’ view of public education changed through the course of the pandemic.

In the period before COVID (January-March), the sector’s apparent accountability, responsiveness to society, and a focus on economic value creation had the most influence on perceptions of the sector’s leadership.

In the first wave (April-June), ethics and balancing the needs of different groups became more important. Accountability, economic value creation and responsiveness to societal needs were also important. Performance scores improved across all five factors.

This possibly reflects the optimistic discourse around vaccine research, producing job-ready graduates and an element of sympathy for universities, as university staff lost their jobs and international students were left to fend for themselves.

In the second wave (July-September), the focus shifted away from the sector’s economic contributions and its responsiveness to society. Instead, ethics, accountability and balancing the needs of different groups became most important.

Performance scores for balancing the needs of different groups decreased. This possibly reflects the changes to tertiary education funding, which triggered backlash from both domestic and international students.

Rethinking the role of universities

Australians have important decisions to make on the role of public education. Rather than positioning public education and universities as a panacea for economic recovery, a wider view is required.

Universities are uniquely positioned to serve the public good. The purpose of education leadership itself has been described as being “as and for public good”. This insight is reflected in the actions of university benefactors, who are motivated by a belief in the public good that only universities can create.

Although philanthropic support is vital, it is in the national interest to properly fund universities to enable them to serve and enhance the public good as only universities can.

– ref. Pandemic widens gap between government and Australians’ view of education – https://theconversation.com/pandemic-widens-gap-between-government-and-australians-view-of-education-148991