Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Robert Breunig, Professor of Economics and Director, Tax and Transfer Policy Institute, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

Polls point to a decisive defeat for Donald Trump. But his unexpected win in 2016 still has opponents rattled, fearing the same divisive rhetoric that characterised his 2016 campaign could help him scrape home.

The US has not been so divided by politics, religion and identity in decades. Particularly troubling are the nation’s inflamed ethnic divisions.

Overall, polls show a majority of voters disapprove of Trump’s handling of “race relations”.

But now, as in 2016, what matters is the view of voters in the “rust-belt” states of Iowa, Wisconsin, Michigan, Ohio and Pennsylvannia, which all swung to Trump in 2016 on the back of strong support from white working-class voters.

Read more: Who exactly is Trump’s ‘base’? Why white, working-class voters could be key to the US election

Trump’s success depended on personal economic concerns being pipped by “racialised economics”, argue politics professors John Sides, Michael Tesler and Lynn Vavreck in their influential 2018 book Identity Crisis: The 2016 Presidential Campaign and the Battle for the Meaning of America:

By racialised economics they mean the important sentiment underlying Trump’s support was not “I might lose my job” but “people in my group are losing jobs to that other group”. Individualised economic anxiety was replaced by group fears and perceived grievances.

Our more recent research, using a nationally representative sample of nearly 500,000 Americans, largely supports this contention. It also suggests that behind the appeal of this ethnic identity politics hide deeper issues of social disconnectedness.

With Trump’s mishandling of the COVID-19 pandemic dominating 2020, and an opponent who isn’t Hillary Clinton, the dog whistling to white voters looks unlikely to work as it did four years ago.

But the problems Trump has weaponised won’t be defused merely by his defeat.

For Biden to make good on his promise to heal the nation’s divisions, he will need to address the social disconnection providing fertile conditions for racialised economics.

The psychology driving racial animus

To analyse the significance of racialised economics in the US, we combined county-level data on economic indicators with individual-level well-being and socioeconomic data. Our primary data source was nearly 500,000 observations from the US Gallup Daily Poll (which has polled 500 American adults every day since 2008). Our data set covered the period 2014 to 2018.

The key things we wanted to analyse from this information were measures of “relatedness”, “social capital” and “worry”, cross-relating these with “racial animus” and voting preference.

Relatedness reflects personal security and fulfilment from social connection. It is measured through responses to questions such as “I cannot imagine living in a better community”, “The area where I live is perfect for me” and “my friends and family give me energy every day”.

Social capital is also about connectedness, but to do with community cohesion rather than the personal experience of relationships. It is measured through things like the extent to which people know their neighbours and participate in community activities. Such connections have declined precipitously over the past 50 years. In particular, the share of adults who say most people can be trusted has fallen from 46% in the 1970s to 31%.

Worry is measured by a simple question of whether people experienced worry yesterday.

Racial animus means racial prejudice. We measure it at a county level using Google searches involving racist key words.

Read more: Racism has long shaped US presidential elections. Here’s how it might play out in 2020

High anxiety, low relatedness

Just as other researchers have found, our county-level results show a correlation between racial animus and Trump’s support in both the 2016 Republican primary race and the presidential election.

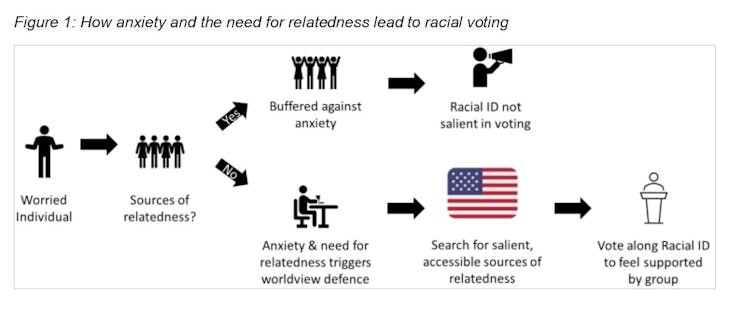

More importantly, they also show Trump’s support correlated with relatively high rates of anxiety and relatively low levels of relatedness – and that higher relatedness would have been enough to negate the effect of racial animus.

This suggests people lacking a sense of relatedness in their own environment look to higher-level connections like patriotism and ethnic identity.

That conclusion is supported by social psychology experiments showing that stoking anxiety leads to exaggerated loyalty to an in-group and disdain for other groups.

As cognitive scientist Colin Holbrook and his colleages explain:

Indeed, numerous studies have found that initially conscious reminders of threats that do not subsequently arouse conscious distress engender a form of evaluation bias termed worldview defence – the polarisation of ratings for pleasant and against aversive cultural attitudes.

Read more: 5 reasons not to underestimate far-right extremists

Diversity and social capital

None of this is to suggest declining connectedness and heightened anxiety is the only reason people voted for Trump. The rural communities of “heartland America” that are traditionally majority Republican typically have high social capital (through church affiliations and the like).

But in the key swing “rust-belt” states – constituencies to whom Trump promised to bring back manufacturing and mining jobs – our research suggests worry and anxiety channelled into ethnic group identification was the decisive factor. These areas showed the lowest rates of relatedness in the US.

How anxiety and the need for relatedness lead to racial voting

As he desperately tries to repeat his 2016 success, Trump’s “greatest hits” campaign has again sought to stoke the group fears of white voters.

His campaign has made some effort to suggest he has ethnically diverse supporters, but this is largely seen as as attempt to assure white women he isn’t a racist.

On the other hand, he has flubbed repeated opportunities to condemn white nationalism, defended Confederate statues, demonised the Black Lives Matter movement and made unsubtle statements about protecting suburbanites from “low-income housing”.

Such rhetoric, though, has been overtaken by events – namely Trump’s dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic and failure to deliver a health-care plan. His other key strengths in 2106 – his appeal as an “outsider”, his promise to “drain the swamp”, his apparent unfiltered “candour”, and his assurances he would fix everything – are no longer so compelling.

But though Biden may well win the rustbelt states, these communities remain economically and cultural insecure, with thinning social capital. Their vulnerability to racial rhetoric remains.

To fulfil his promise to unite America, therefore, a Biden administration will need to address the underlying issues of low social capital and connectedness.

– ref. Hijacking anxiety: how Trump weaponised social alienation into ‘racialised economics’ – https://theconversation.com/hijacking-anxiety-how-trump-weaponised-social-alienation-into-racialised-economics-147366